I Can’t Bring Myself to See it Starting: Mark Hollis and Talk Talk

By Joseph Barresi

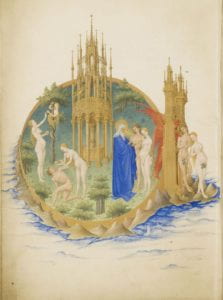

I had a trundle bed in New Zealand. It belonged to my landlords and I slept on it in the basement room they had set up for their preteen daughter, until she developed a fear of living in a semi-detached space, darker and cooler, from her parents and younger brother upstairs. The bedroom was a soft pink when I moved in, and over three sunny late spring evenings in early December, I rolled white paint over it with my landlady, Kristi. It was just the trundle, there, under the bed, soft maple slats on its rollers. My landlords had taken the single futon mattress that had rested on the trundle for family guests that would occasionally visit. I would store miscellaneous shit in the gap between my mattress and the wood: half-dirty shirts and half-empty bottles of wine. They left, however, the heavy canvas curtains imprinted with the same four fairies in various states of repose and reflection, by soft shallow pools in verdant green shifting light. Two were brunette, one blonde, and one redhead. They wore Easter-colored dresses.

Around the New Year, my girlfriend called me from across the sea and told me that she had adopted a dog, an Australian shepherd mix, which she named Buckley. They shared a birthday and it was winter where they were. A week later, she told me she had decided she wouldn’t be coming.

At the end of February, Mark Hollis died. Someone on Facebook posted “I Believe in You” from 1988’s “Spirit of Eden.” I had never sat down and listened to Hollis’s band, Talk Talk, before, but I understood they were a band I should know and appreciate. I waded the streams of indie music, becoming adult. At first, I heard “It’s My Life” on Eighties, Nineties, and Now radio stations. I couldn’t distinguish it from “Everybody Wants to Rule the World,” nor even “Rio.” Later I would come to know Talk Talk as essentialism, and as a keystone in the pattern of creative romantic individualism, to which I was indebted without really understanding in a visceral way. I had a dreamlike notion, informed by nothing concrete, that they had created art for a cosmic vision that heeded neither expectation nor demand.

I had been desolated before. We had abandoned one another at critical places in our lives before. When I was younger, I swore to myself that I would never speak to her again, while driving in California, in melodramatic, hollow anger. Somehow I ended up again a summer later in the attic room of her parents’ house across the country, naked and weeping quietly in the afternoon sun that fell through the window onto her bed sheets. Neither of us knew why.

Now I lay on another bed, on the other side of the planet, in another summer; a summer that I cheated for, leaving the Northern hemisphere and arriving to greet it, two seasons too early. When I arrived in October, it was still mid-spring in Auckland and a bitter wind blew gray and sideways through the hills and wet.

I would weep every day for much of January and February and feel the hollow around my solar plexus caving and quaking. It was an exhausting relief and put me into a sleep, soundless and solemn, compared to fitful anxieties of nighttime. I didn’t want to fall asleep at night knowing how the morning would feel, the most acutely lonely time. I didn’t want to do much but sleep during the day. The antipodean sunlight sifted soft green through the harakeke flax planted outside my western window at my head. I worked nights at the pub downtown, and I would rise around five in the evening, the space around my eyes heavy and starched with hungry tears. The summer felt hollow, surrounded in an impossibly Edenic landscape through which I would now tread with unexpected and intense solitude. All that I wanted then was to share it with the one.

“Summer bled of Eden / Easter’s heir uncrowns / Another destiny lies leeched / Upon the ground”

When I clicked the YouTube link to Talk Talk’s “Eden,” I didn’t expect to be confronted with an aural landscape that mirrored my desolation here on my island, alone at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, washed by sudden storms that blew in and out with intense beating and erratica of the flight path of a monarch butterfly. A softly echoed rim-hit snare beat. A suspended piano progression intertwined like a misty vine with a wandering tremolo Stratocaster. Exploratory in its melancholy, persevering through doubt and upset like the summer sun falling in the waning afternoon onto my tired eyes through the undulating flax, the gray boughs of the yet-fruitless feijoa tree.

“I just can’t bring myself to see it starting.”

I knew this time was different. Somehow, despite everything I hoped and held in the endless moments of those days, muddled in winter and summer ideas that twisted and fell and lost meaning, through six years of turmoil and beauty and life and death, I quietly decided that it truly was over. I wouldn’t tell myself that, impossibly finding the words to an idea that was beyond words. Halfway through the song, as Hollis cries out, “a time for passing,” the chord structure shifts and resolves in the voice of a soft green organ, a synth choral croon that layers like drifting white blossoms. “Spirit, hear it in my spirit,” Hollis softly proclaims, a tiny flower sprouting from the greenery.

It became a daily ritual, like my tears. I would fold out my ninety-nine dollar Acer Chromebook flat and play the album through its tiny speakers, still powerful if I turned the volume all the way up. I would drift away like the sailed strings and arrow-shot trumpet that begins the album on “The Rainbow.” To faceless dreams and meaningless unclenching, the sound emanated in eddies beneath my prone body as if I floated in a raft on a creek. “Oh yeah, the world’s turned upside down.” At twelve minutes into the album, halfway through the opening triptych of “The Rainbow,””Eden,” and ”Desire,” I would jolt to the rising and modulating cry of the organ’s minor chord, matching Hollis’s desperate rising vocal. “Everybody will need someone to live by,” finding me again in my dreamlike, emptied, waking life. My dreams felt more my own than the world at which I looked around and walked upon. The loudness fell like a dropping tide, I too disintegrated again into sleep.

The cover of the album was stolen from the nonsensical dreams of my childhood, now placed before me in my waking life. An impression of an unnamed deciduous rises from a foreign, endless ocean, adorned with seashells hung delicately, like swinging earrings; a southerly-looking puffin holds hind-facing regard. I laid in my bed and gazed up at that tree. Chrysalises hatched and monarchs began to sail by. The summer rolled on.

“Nature’s son / Don’t you know how life goes on / Desperately befriending the crowd / To incessantly drive on / Dress in gold’s surrendering gown / Heaven bless you in your calm / My gentle friend Heaven bless you”

It was Hollis’s death that brought me to his art. His voice appeared to me in a dream and spoke to me, guiding me like a martyr, though not to death for any cause. But to resolve, in Eden.

Joseph Barresi is a New England-based travel writer, poet, and country-western musician. He is the author of the self-published poetry chapbook, “And fisherman hold flowers: Reflections on Aotearoa New Zealand.” Raised in the American West, he currently lives outside of Portland, Maine, where he works predominantly sweeping floors.