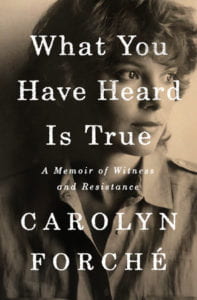

A Poet Reflects on Friendship and Hope in “What You Have Heard is True”

By Nicolette Natale

By Nicolette Natale

It begins with a stranger in a white Toyota Hiace with an El Salvador license plate, the car that pulls up outside poet Carolyn Forché’s house in California. It is the 1970s, and she is needed, the stranger tells her. El Salvador is about to go to war, and she needs to bear witness, to make people in North America understand.

The stranger is Leonel Gomez Vides, and he is central to Carolyn Forché’s riveting memoir, “What You Have Heard Is True,” a finalist for the 2019 National Book Award for non-fiction. As readers we understand that Gomez Vides deliberately presents himself as a mystery; he is a man who has posters of both Che Guevara and Mussolini in one of his homes so as not to reveal his political leanings, at least on the surface level.

But the crux of his identity is besides the point. To Forché, he is a mentor, and that is the role he plays in the book. Once Forché lets him in, figuratively and literally, to her house, he tells her about the conditions in El Salvador. Sitting at her kitchen table, he explains that his country is in a dire state of poverty. The majority of the population is malnourished and does not have access to utilities like running water or electricity. The workers are heavily exploited and severely underpaid.

“I am asking you to imagine it,” Gomez Vides says. Gomez Vides’s insistence that she look closely becomes a motif in their relationship, and in this book. When they travel together to El Salvdor, Gomez Vides instructs her to write down what she sees, to document it all, but he also warns her that this will not be a white savior narrative.

“You could call this my reverse Peace Corps,” he says. “You would be coming to our country not to help us but so that we can help you.” His jokes about North American anthropology majors who come to El Salvador to incite change, unaware of how they replicate colonialist power structures, are depressingly and humorously spot-on. Gomez Vides subverts the pitying North American gaze into one that holds the United States accountable for many of the conditions in El Salvador. He won’t let Forché forget that these countries are connected.

While driving her around in his Toyota in El Salvador, he asks Forché to literally describe what she sees: “Papu, what are you seeing?” She responds, “What do you mean? A road. Trees.” He turns this moment into a learning exercise, reversing the car and asking her to tell him when she sees something besides trees. Slowly, she sees the plethora of champas, small shacks made out of mud and newspapers, in the forest they are driving past.

Early in the book, Gomez Vides challenges her by asking, “Are you going to write poetry about yourself for the rest of your life?” It’s clear that he believes that poets have a responsibility, not only to look closely, but to also look beyond themselves, to confront injustice and force people to see the truth. Forché’s famous poem, “The Colonel” (from which the title of this memoir comes), is a perfect example of this kind of poetic activism. That poem is about the way different people respond to stories about oppression: some listen, while others choose to ignore the brutal truth. What Forché asks of us in her poem, and now memoir, is what Gomez Vides asked her so many moons ago: to resist complicity in larger oppressive power structures.

There is an expression used when discussing privilege in activist spaces: “Fish don’t know they’re wet.” In many ways, Gomez Vidas makes Forché aware of the water she swims in. To slow down, to take nothing for granted. Forché’s oblivion, Gomez Vidas knows, doesn’t stem from callousness, but from privilege and an American education that fails to teach people about Central America. In telling the story about her time in El Salvador, Forché makes American readers aware that they, too, are wet.

Although it’s a politically urgent book, Forché’s memoir never reads as a polemic. At its core, this is a book about the transformative power of friendship and reads like a love letter to Gomez Vides. Forché’s relationship with him opened her ears and eyes and shaped her career as a poet. She cites her experience in El Salvador as the catalyst for her learning to bear witness to people’s suffering; such witnessing was the inspiration for an anthology of poetry called “Against Forgetting,” which she spent thirteen years curating. A practiced listener, she asks readers in the introduction to her anthology to accept the second-hand trauma they may receive through reading poetry by those who document and resist various social and political violence. Implicitly, she asks the same of readers now in her memoir.

Reading this book makes it impossible not to crave a friendship like theirs: one that acknowledges the reality of oppressive conditions even as it persistently and stubbornly believes a better world is possible.

Nicolette Natale is a recent NYU graduate who studied English and social & cultural analysis. She is deeply grateful for educators and librarians.