https://wp.nyu.edu/davidluddenhomepage/2023/10/18/conditions-in-gaza-2023/

Category Archives: Global Asia Blog

On Colonialism and Empire

Mobile Missionary Spaces: The Basel Mission

The BASEL MISSION mission was founded as the German Missionary Society in 1815. The mission later changed its name to the Basel Evangelical Missionary Society, and finally the Basel Mission. The society built a school to train Dutch and British missionaries in 1816. Since this time, the mission has worked in Russia and the Gold Coast (Ghana) from 1828, India from 1834, China from 1847, Cameroon from 1886, Borneo from 1921, Nigeria from 1951, and Latin America and the Sudan from 1972 and 1973. On 18 December 1828, the Basel Mission Society, coordinating with the Danish Missionary Society, sent its first missionaries, Johannes Phillip Henke, Gottlieb Holzwarth, Carl Friedrich Salbach and Johannes Gottlieb Schmid, to take up work in the Danish Protectorate at Christiansborg, Gold Coast.[3] On 21 March 1832, a second group of missionaries including Andreas Riis, Peter Peterson Jäger, and Christian Heinze, the first mission doctor, arrived on the Gold Coast only to discover that Henke had died four months earlier.

A major focus for the Basel Mission was to create employment opportunities for the people of the area where each mission is located. To this end the society taught printing, tile manufacturing, and weaving, and employed people in these fields.[4] The Basel Mission tile factory in Mangalore, India, is such an endeavour.

https://architexturez.net/doc/az-cf-193723

https://architexturez.net/doc/az-cf-1937248

With the decline of the terracotta industry in the latter half of the 19th century, local factories which sustained a century of cross-continental trade are being demolished and I have made use of its material remains as a point of departure to ‘make’ and accommodate reuse and repair as a core focus in my practice :

https://architexturez.net/doc/az-cf-193590

https://architexturez.net/doc/az-cf-193632

Arjit is currently the 2021 James Harrison Seteedman fellow (Washington University in St Louis,MO,USA) and I will be travelling to the US next year to present the fellowship. Maybe we can meet then. Do let me know if your students or any program wants to work on this subject. My partner is currently enrolled as a phd fellow in AArhus School of Architecture, Denmark and her research focus is on the ‘ecologies of residue’ as the tile travelled, its imprints in contemporary building culture.

IIAS: Visualising history and space in the Basel Mission Archives (PDF file).

Assignments

All assignments go into the Student Google Folder. Assignments are due in the folder by midnight on the date listed below.

These are one-page minimum reflections on the prompt listed below, based on readings, discussion, and field visits. The first four are phrased as questions to which I append my own answers AFTER I have read through student papers, to clarify points that that I want to get across in the first part of the cours.

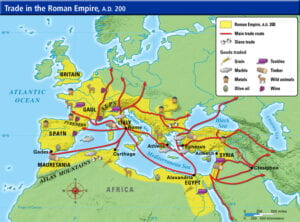

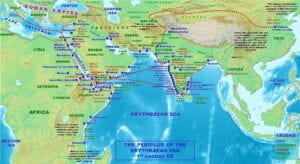

1. Thursday Jan 5. Q: What were the causes of the plagues in ancient Rome? (And think about why we do not have accounts of ancient plagues in Asia.) A: Roman demand for Asian products brought pepper and other commodities to the ancient Mediterranean, some by land but mostly by sea, up the Red Sea and Persian Gulf. Roman consumer demand also brought plague, which infected troops fighting Roman imperial wars in Mesopotamia, who carried both Antonine and Justinian plagues back to Rome. Soldiers and workers died during the Justinian Plague in sufficient numbers to weaken Roman imperial power, notably in Syria, where early Muslim communities encountered the plague. (We lack records of plague in ancient Asia because of the mobility and low-density of populations in areas where plague travelled, but there were clearly outbreaks in densely populated parts of India and China.)

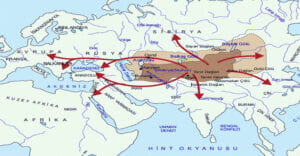

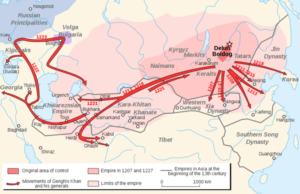

2. Friday Jan 6. Q: How did the Black Death reflect historical change in the previous millennium? A: The Mongol Empire built routes of mobility and centers of trade and political power inside expansive Turkic spaces of mobility all across the steppe. Mongol expansion increased the mobility of people and animals that carried the plague to Europe. At the same time, centuries of agricultural and population expansion, particularly in warm centuries after 800, increased the density of populations in places where pandemics became killer epidemics.

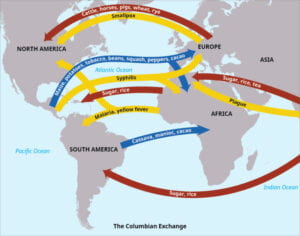

3. Saturday Jan 7. Q: What could be said to be historical stages in the globalization of disease? A: Stage One is the ancient (pre-600CE) commercial interaction of Europe and Mediterranean, by land and sea. Stage two: their more intensive late medieval interaction after the Mongols (note the travels of Marco Polo in the 1300s). Three: the post-1500 seaborne Columbian exchange. Stage Four: the post-1600 global expansion of European seaborne empires. Those can reasonably defined as the four main historical stages in the globalization of pandemic disease into the 20th century.

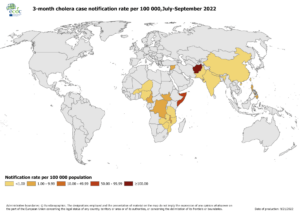

4. Monday Jan 9. Q: Consider the case of cholera as pandemic, epidemic, and endemic? A: Cholera seems originally to have been endemic in deltaic localities in lower Bengal (and perhaps in some other watery coastal regions of tropical India). It became epidemic in coastal regions because of increasing population density in urban areas driven by ongoing commercial and English imperial expansion, around Madras and Calcutta, in 1817. Cholera became pandemic by traveling with troops, merchants, and other migrants along routes of British imperial globalization, which eventually brought cholera to coastal regions and to port cities around the world, including New York City.

5. Tuesday Jan 10. Write your paper on your BRAC presentation project theme,.

6. Wednesday Jan 11. Consider your theme in the context of socio-economic inequality.

7. Thursday Jan 12. Discuss pathocoenosis in the Bangladesh context

8. Monday Jan 16. Discuss the politics of public health in the context of globalization.

9. Tuesday Jan 17. Write a brief description of your paper topic and indicate some source materials that you will use.

10. Wednesday Jan 18. Write up a short presentation your final paper.

10 page paper due at midnight on Jan 20. Discussion and Presentations in class. Jan 19-20.

maps

Indian Ocean Connections to Asian Trade: The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea

Indian Ocean Connections to Asian Trade: The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea

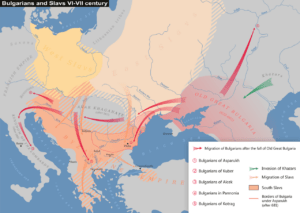

Turkic Migrations (550-1200). In 552 a powerful new Turkic confederacy developed in the Altai Mountains. It spread from China to the Caspian Sea, pushing Bulgarian and Slav nomad warriors deeper into Europe.

Mongol Imperial Expansion: The Mongol Empire covered the most contiguous territory in history, during the period 1206- 1368.

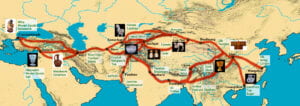

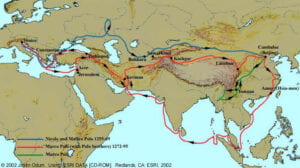

Marco Polo: the Venetian explorer Marco Polo famously used the Silk Road to travel from Italy to China, under the protection of Mongols, arrived in Kublai Khan’s summer palace, Xanadu, in 1275. He spent 24 years in Asia, at Kublai Khan’s court, and returned to Venice, again via the Silk Road routes, in 1295.

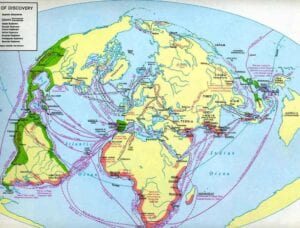

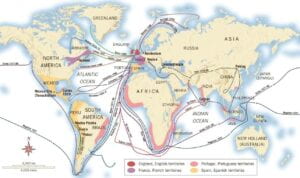

European Seaborne Empire and Exploration: 1500-1850

Cholera— in Earth.org: Pandemic cholera began its travels in 1817, in the Ganges Delta, with contaminated rice. In 1837, it reached Kabul, in Afghanistan and Southeast Asia, carried by British Troops, and spread into Iran and Derbent (Russia), on trade routes. In 1845, it crossed the Arabian Sea on ships; it spread north into Iran and Iraq, along the Tigris and Euphrates, and found its way into the Black Sea and Istanbul; from there it traveled to Europe, and in 1848m reached Norway, England, Spain, the Balkans, and North Africa (when pilgrims from cholera-plagued Mecca returned to Egypt). In 1849, it was carried to New York and New Orleans on ships loaded with drinking water.

Routes of the second world cholera pandemic (1826-1837).

D. HU ET. AL. PNAS 113, 46 (14 NOVEMBER 2016) © NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES