Graciela Blandon /

Asociación Pro Derechos Humanos de Andalucía (APDHA) /

Cadiz, Spain /

I must admit, working in the human rights field is taxing. I’m overjoyed to have met the APDHA team and every day I give thanks for the opportunity to wake up in Cadiz. But the second I open my laptop, I’m bombarded with stories of death and abuse.

Currently, I’m working on compiling this year’s reports on migration via the Spanish Southern Border (Frontera Sur). In an Excel sheet, I tally up the number of cadavers, minors, and pateras that cross into Europe from Morocco and Africa. The headlines are always intense: “A young girl recently arrived via dinghy relates how she saw her brother’s body thrown overboard after his death.” I’m reminded of Miriam Ticktin’s article, “Thinking Beyond Humanitarian Borders.” She holds that children, families, and animals are often instrumentalized in human rights campaigns for their semiotic value. Recall the iconic image of three-year-old migrant Alan Kurdi whose death moved the world.

The “perfect” migrant is a blameless victim of the state. This two-dimensional character is undoubtedly useful in building broad-based support for human rights efforts. Shock at the defilement of the innocent motivates individuals to act. However, I’m afraid of the desensitization to and normalization of suffering that comes with consuming so many distressing scenes, not to mention the dehumanization of the migrants themselves–the reduction of their lives and deaths to numbers on a spreadsheet.

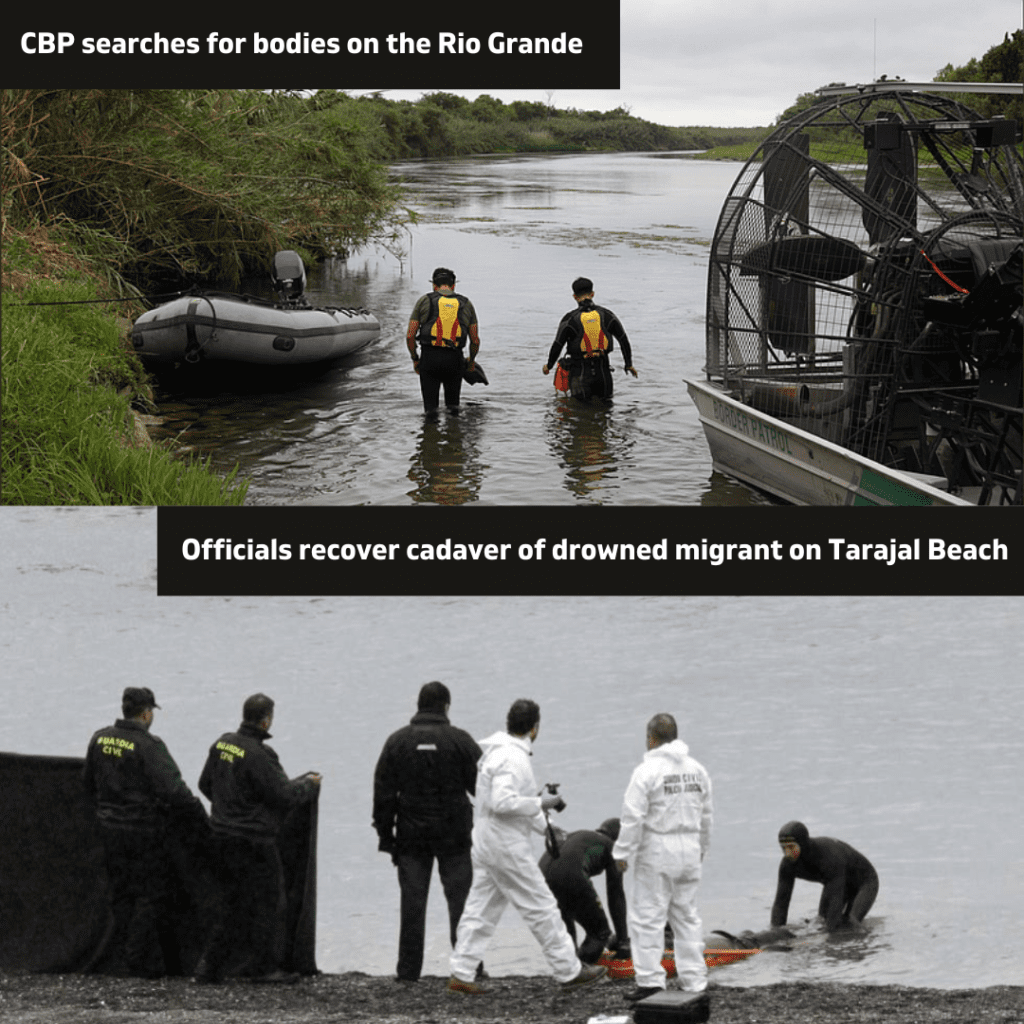

But in truth, life on the border is constantly underscored by such traumatic news. In El Paso (another southern border of the world) it’s part of one’s daily routine to learn that a mile away the body of a migrant was found drowned, broken, beaten. In fact, the more I read and learn about migration on Spain’s Frontera Sur, the more I find that, on a micro level, the difference of an ocean between Cadiz and El Paso is nearly negligible. The same discourse exists: the same violence, the same polemic of illegality, the same racist archetypes.

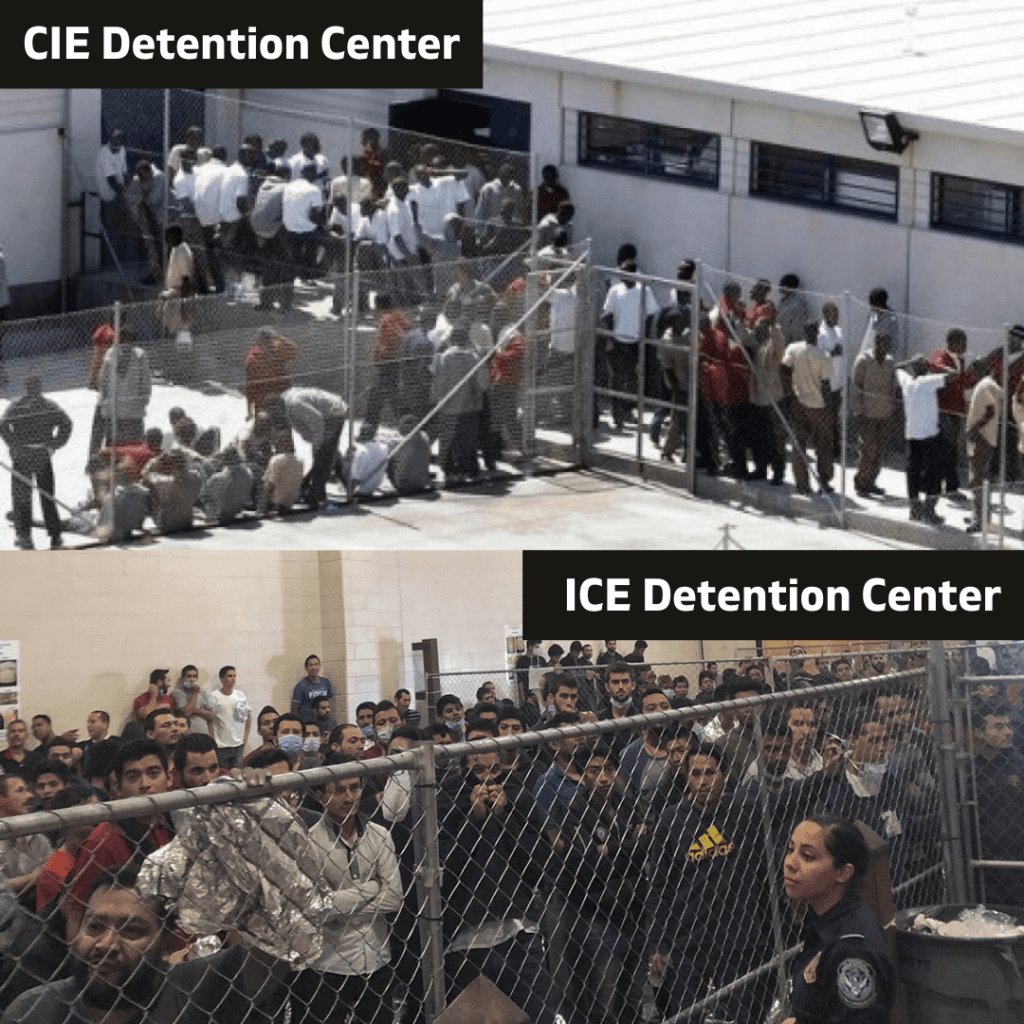

I clearly see a framework for how migration works internationally; it’s like some sick game of Mad Libs where only the names of the places change. Images from Melilla’s walls and Ceuta’s beaches are strikingly familiar to me, as are opinion pieces about how Spain should deal with the “invasion” and “crisis” on the southern border. Recently, I ran into a migrant detention center; in Spain, they’re named CIEs. My first thought upon encountering the CIE was that it was an anagram of ICE, and in fact, it looked no different than the ICE detention center near my home. In both, migrant women and children suffer rape and abuse.

I see my presence here as an exercise in international solidarity. I’ve realized that though we cannot generalize about everything, the struggles of El Paso and Cadiz are deeply connected, and the political landscapes that shape the lives and identities of these city’s residents exist parallel to each other. Thus, I’m feeling extremely at home in Cadiz, in more ways than one.