Karanjit Singh

Gu Chu Sum

Dharamsala, India

My time at Gu Chu Sum proved to be very helpful in understanding the motivations of many of the former political prisoners from Tibet that have risked their entire lives to stand up for a cause they really believe in. Gu Chu Sum was established initially in 1991. The name is three numbers, 9, 10, and 3 in the Tibetan language, and was chosen because it represents the dates (September 9, October 10, and March 3) when massive pro-independence demonstrations broke out in Lhasa during 1987-1988, where hundreds of protesters were arrested, imprisoned and tortured in Chinese prisons.

Initially I had a few problems working with the community, mainly because of the language barrier; although I know a little Tibetan, there were several accents that I was unaware of prior to my arrival here which set me back for a bit. Most of the staff were recent refugees who also happened to be former political prisoners inside Tibet that have moved into exile. Gu Chu Sum is currently led by the Vice President, Namgyal Dolkar, a passionate young Tibetan woman. Namgyal Dolkar is also one of the first few Tibetans to have successfully applied for an Indian citizenship. As Tibetan refugees living in India, it is in fact very difficult to obtain an Indian citizenship, even if one was born in India to a refugee family.

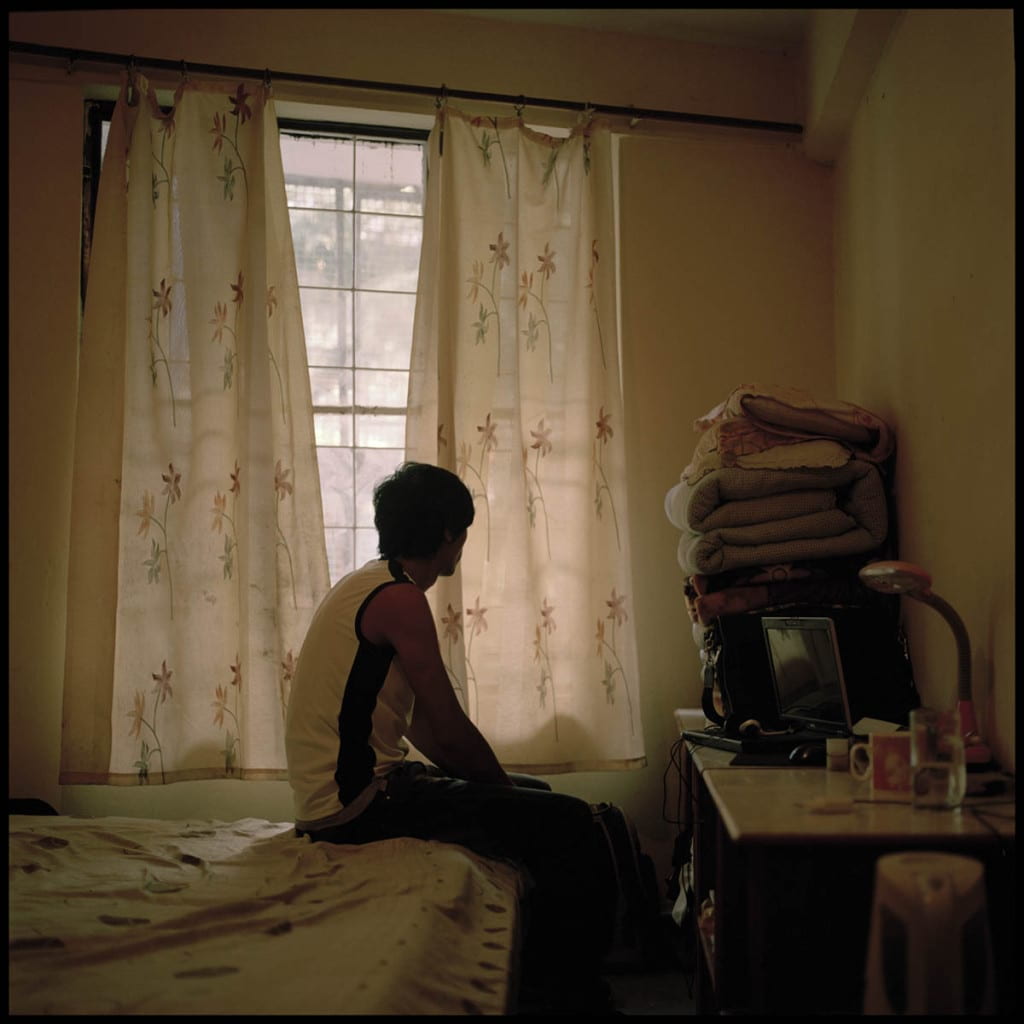

It might seem like a job to some people but for me I can envisage how this is shaping my personality drastically. I am inspired everyday to continue my fight for freedom and feel lucky that I get to take part in it. There used to be a time when it was too difficult and overpowering to hear the testimonies of different political prisoners who are all martyrs in my eyes leave apart the emotional intensity/pressure of reciting or translating. But as I continue doing so I realize how it is making me a stronger person; a stronger Tibetan

I truly believe each Tibetan holds a responsibility and owes it to their ancestors; and that succumbs me to work harder.”

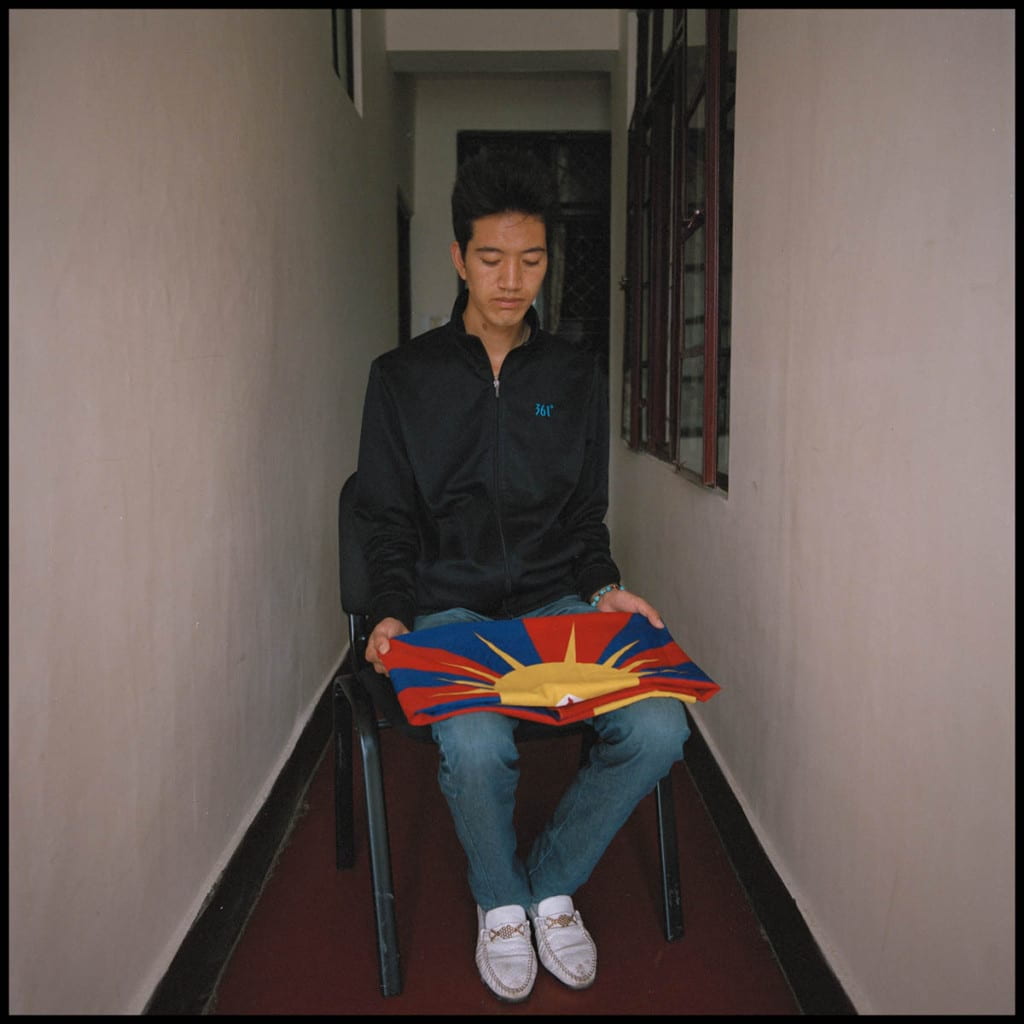

At Gu Chu Sum, I took up the task of teaching photography and English to a group former prisoners who had recently escaped Tibet and had come into exile in India. During the two month long course, we were able to read several short stories written by prominent Tibetan authors in exile. The idea was to emphasize political and cultural vocabulary that has been used by exiled writers so that the students could ultimately pen stories of their own. I was particularly interested in how these students, all young activists from Tibet in their late twenties and early thirties, understood the Tibetan issue. For many of the people who have lived only in exile, the problems faced by Tibetans inside Tibet can sometimes be hard to grasp, as there is a lack of clear information regarding what is happening in the region due to heavy surveillance and censorship.

It was fascinating to hear stories from the students about their time inside their homeland. Out of the 7 students I taught, 4 had been involved in the 2008 protests that erupted in Lhasa during the Beijing Olympics. One of them happily recalled how he, in protest to the Olympic games and China’s continued disregard of Tibetan history and language, sneaked into his local school, cut the computer wires, and wrote “Free Tibet” on the chalkboard of every classroom. The authorities obviously found out about him, but only after he was on the run. Stories like this are not one but many, stories of youngsters who acted out against an oppressive system in any small way they could.