Emily Pederson

National Front for the Fight for Socialism

San Cristobal de las Casas, Chiapas

“Los que parecian mudos al terminar el ano 1993, amanecieron con palabras en sus bocas el dia primero de enero de 1994, no solo los indios sino los mestizos intelectuales. Ahora somos conocidos los mayas, zoques y otras etnias en todo el mundo. Si las palabras llegaran a surtir sus efectos en la realidad, tendriamos un Mexico nuevo, mucho mejor, y en nuestros pueblos indigenas poco a poco habria vivienda, bonanzas, nueva vida. Pero las plasticas se conduecen mal o las palabras se las lleva el viento, por no encontrar firmeza en la realidad. Si no se cumplieran, no unicamente regresariamos al sufrimiento de antes, si no al contrario, el sol perderia brillo ante nuestros ojos.”

Translation:

“Those who seemed mute at the end of the year 1993 woke up with words in their mouths on the first of January of 1994, not just the indigenous, but even the mestizo intellectuals. Right now, we, the Mayans, Zoques, and other ethnicities, are known all over the world. If the mending words go as far as to take effect in reality, we will have a new Mexico, a much better one, and in our indigenous towns little by little there will be housing, well being, new life. But the talks are conducted badly or the wind takes the words away, because they don’t find commitment in reality. If they are not fulfilled, not only will we go back to the suffering of before, if they are not the sun will lose its shine before our eyes.”

–Kuxul Waychiletik, “El Levantamiento Armado,” Suenos Despiertos (“The Armed Uprising,” Waking Dreams)

In 1994, thousands of indigenous soldiers died for the rights of their people. Thousands of people in the Mexican army died, too, because the Zapatistas’ war was on the Mexican government, so their guns were pointed at the government’s military. Many who weren’t on either side were caught in the crossfire. The whole world looked at Chiapas and the government promised to make things better for the indigenous, who had been treated like they had no rights to land, health, justice, decent pay for their labor, autonomy, or education since the time of the conquest.

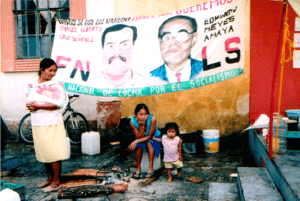

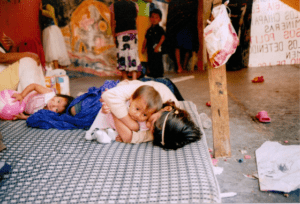

17 years later, the racism that plagued Chiapas isn’t as bad as it was. The indigenous have a voice now, but the progress is little by little. In some ways things have stayed the same. Sometimes justice is still not done when crimes like murder, robbery or rape are committed against indigenous people. When I came back to San Cristobal de las Casas after being away in Yajalon, five Ch’ol families had set up a sit-in in the one of the main squares of the city. The wooden platform they were sleeping on was covered in signs about paramilitarism in Chiapas and being expelled from their lands. A few weeks earlier, near the end of June, a group of men with ski masks and guns led by one Marciano Gaspar Jimenez came to their homes at 2:00 in the morning and threatened to kill their littlest children if they didn’t leave their land. The families were robbed of everything they had and had to flee their homes that night. As of now the gunmen are still free.

When I came back to San Cristobal de las Casas after being away in Yajalon, five Ch’ol families had set up a sit-in in the one of the main squares of the city. The wooden platform they were sleeping on was covered in signs about paramilitarism in Chiapas and being expelled from their lands. A few weeks earlier, near the end of June, a group of men with ski masks and guns led by one Marciano Gaspar Jimenez came to their homes at 2:00 in the morning and threatened to kill their littlest children if they didn’t leave their land. The families were robbed of everything they had and had to flee their homes that night. As of now the gunmen are still free.

The families belong to a campesino organization called the FNLS (Frente Nacional para el Lucha para el Socialism/National Front for the Fight for Socialism). It’s not uncommon for people who are part of this organization to get threatened and intimidated. When the people of Chiapas organize from below, trouble always comes from above. In protest of what happened to them, the families and some of their compañeros from the FNLS set up a sit-in in one of the main squares of San Cristobal, a city six hours from their town, and another in its State Council for Human Rights’ (SCHR’s) office. They handed out information about their situation to the passerby and asked for help or solidarity from human rights groups and the government for a month. They wanted the aggressors punished, reparations for the damages, and legal documents proving their ownership of the land. The government itself gave them the land after they were displaced two times before, years earlier, but hasn’t given them proof of ownership. An official was supposed to come arrange for the paperwork a week before the expulsion, but he never showed up.

The families belong to a campesino organization called the FNLS (Frente Nacional para el Lucha para el Socialism/National Front for the Fight for Socialism). It’s not uncommon for people who are part of this organization to get threatened and intimidated. When the people of Chiapas organize from below, trouble always comes from above. In protest of what happened to them, the families and some of their compañeros from the FNLS set up a sit-in in one of the main squares of San Cristobal, a city six hours from their town, and another in its State Council for Human Rights’ (SCHR’s) office. They handed out information about their situation to the passerby and asked for help or solidarity from human rights groups and the government for a month. They wanted the aggressors punished, reparations for the damages, and legal documents proving their ownership of the land. The government itself gave them the land after they were displaced two times before, years earlier, but hasn’t given them proof of ownership. An official was supposed to come arrange for the paperwork a week before the expulsion, but he never showed up.

The government gave the families no response other than public space officials coming to tell them that the space for sit-ins was on the other side of the plaza. The most respected human rights group in the city gave them the cold shoulder because its people only help their own, which means those who belong to the Other Campaign (the Zapatista political movement). The SCHR told them they were violating its property and bickered with them about being in the way, about the kids using the bathroom, about why they had so many children in the first place.

Eventually, the families decided to go back home even though the paramilitary was still roaming free in their town. Staying at the sit-ins in San Cristobal was unsustainable, the strategy wasn’t working, and they needed their land back. They convinced the SCHR to provide them with buses and help them get home safely, and on the 22nd of August they returned to their town, Las Conchitas. The night before they left I was taking pictures outside their campsite, one thing led to another and I ended up inside, and the next day went with them to photograph their trip home.

The SCHR sent a car of officials and international observers to head the caravan so that the chances of violence would be less. Along the way, we stopped in two towns to pick up compañeros from the FNLS to go with them in solidarity, most of them carrying their machetes, joking about what they would do if bullets started flying. By the time we got there we must have been more than 70 people. Pulling into the road that leads into the town was tense, but thankfully the paramilitary wasn’t lying in wait. As we marched through the woods to the families’ houses everyone chanted “Get out of las Conchitas paramilitary!” and “Zapata lives and lives and lives!”

The SCHR sent a car of officials and international observers to head the caravan so that the chances of violence would be less. Along the way, we stopped in two towns to pick up compañeros from the FNLS to go with them in solidarity, most of them carrying their machetes, joking about what they would do if bullets started flying. By the time we got there we must have been more than 70 people. Pulling into the road that leads into the town was tense, but thankfully the paramilitary wasn’t lying in wait. As we marched through the woods to the families’ houses everyone chanted “Get out of las Conchitas paramilitary!” and “Zapata lives and lives and lives!”

The families have been home for a week now, and they are getting threatened again. When the men leave the house to go work in the field, the gunmen are waiting, and when they see them they fire bullets into the air.

The families have been home for a week now, and they are getting threatened again. When the men leave the house to go work in the field, the gunmen are waiting, and when they see them they fire bullets into the air.

Today I told Don Antonio, one of the tzeltales I´m working with in Yajalon, about what happened to these five families, and he said, “Asi pasa, porque somos indigenas (that’s what happens, because we’re indigenous.)“

Paramilitaries commit the atrocities that the Mexican army has to pretend it didn’t have anything to do with. “Ejercito y paramilitar es el mismo,” said Don Antonio. “El paramilitar no es el ejercito, pero es el ejercito que les da sus armas. El ejercito no puede matar a sangre frio, pero paramilitar? Si pueden…Nunca van a acabar con los paramilitares (The military and the paramilitaries are the same thing. They’re not part of the military, but it’s the military that gives them their guns. The military can’t kill in cold blood, but a paramilitary? They can…They´re never going to end the paramilitaries.)”