Declan Galvin

United States International University

Kenya

I have been carrying out research with members of Mungiki for the past several months, while staying here in Kenya. Mungiki is a complex network of youth, most of who come from the Kikuyu tribe, which originated in 1987. However, the word “complex” proves to be an understatement and “network” is no more satisfactory in describing them either. Nonetheless, it is this complexity that intrigues me and is what brought me to carryout research with them.

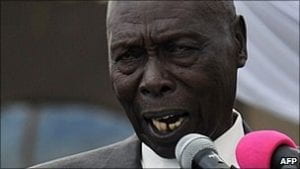

Mungiki began in the late 1980s during what is considered to be the worst time in Kenyan history since independence. This period was the apex of Daniel Arap Moi’s draconian economic and security policies which alienated the entire population, including members of his own Kalenjin tribe; but times were especially hard for the Kikuyu who were among the first to fall victim to Moi’s oppression. Moi had developed nasty tendencies of dismantling the economic base of his political opponents, usually along ethnic lines, and jailing dissenters (especially youth) in the now infamous Nyayo House torture chambers. The research and interviews I have conducted suggest that this is the environment that engendered Mungiki.

However, Mungiki have proven to not fit neatly into the narrative that we may expect from these historical circumstances, i.e., a grassroots resistance movement aiming to subvert the repressive tactics of a dictator. Mungiki, rather, have travelled on a manic journey of faith, violence, and political attitudes showing little consistency or method over time. Mungiki started as embracing Thaaism, a traditional religion from the Mount Kenya region, only to later convert to Islam in the 1990s and Christianity in the early 2000s. They are most known for committing grotesque murders and acts of violence against civilians, including torture and dismemberment; while simultaneously providing social services and livelihood projects at the same communities they plunder. Mungiki have also been inconsistent with their political stances since their inception which includes organizing opposition to Moi, and later supporting him and his establishment.

My research is centered on understanding the rationale of continuous Mungiki transformation over time. I have found, preliminarily, that these transformations can be attributed to the particularities of the Mungiki bureaucracy. My investigation has focused on understanding why people join Mungiki, and what rewards (social or otherwise) they get from such membership. I have found, so far, that the most significant reason for joining Mungiki is to belong to a supportive community. If we build a membership profile of the typical Mungiki recruit, something I am trying to do, we find that most members come from volatile backgrounds including extreme poverty, marginalization, lack of formal education, and especially landlessness. The level of social detachment and alienation that these dynamics promote seem to bare down on the would-be recruits, most of whom cite during our interviews that they remain with Mungiki because of the community it represents.

Moreover I have found that many people early on (before 1994) joined because their friends of relatives encouraged them to join, which underscores that Mungiki was at one point a social project for its members. Furthermore, I have found that there is a history of volunteerism within the group where its members would pay their own travel expenses when attending the various conferences and meetings with other Mungiki members. In addition to this, Mungiki offered small loans to women and widows, designed communal farming programs, and developed various other income-generating projects for its members.

However I am also beginning to find that while these pro-social elements of Mungiki are very real, there seems to be a major distinction between the motives of “regular” Mungiki members and certain Mungiki leaders who seem to be motivated by wealth accumulation and power generation, especially toward the early 2000s. I am finding that this distinction is very significant to understanding the aforementioned faith, political, and violent transformations of the group.

It seems that the major transformations are more closely connected to political and economic gains for the Mungiki leaders than the aspirations of Mungiki members, per se. In other words the main reason for the growth and retention of Mungiki members throughout time is the livelihood and community dimension the group provides, which has remained a constant in Mungiki history; but the leaders will tout the vast membership and network (the most conservative estimates claiming it to be in the hundreds of thousands) and align themselves to various societal shifts in order to generate income or power. One respondent informed me that this was the rationale of Mungiki’s conversion to Islam in the late-1990s by claiming that doing so “the possibilities were endless.” He was suggesting the fear associated with militant Islamist groups in Kenya was at an all-time high because of the Al Qaeda bombing of the US Embassy in Nairobi in 1998.

The leaders of Mungiki saw this as an opportunity to terrify the Kenyan government by staging mass conversions of its membership, and claiming that, according to Ndura Wariunge the then National Coordinator of Mungiki “harassing Mungiki would now be seen as a insult to all Muslims” and that they now called for Kenya to be a nation “guided by the Sharia [Law]” (Mungiki Leaders Convert to Islam, Daily Nation 2000). The Kenyan government became terrified and called for talks with the leadership, and the latter said that they would back-off the rhetoric if the Kenyan government (i.e., Moi) granted them the public transportation (matatu) cartel. Some Mungiki leadership are said to have become millionaires from this deal, making it one of the smartest strategic decision Mungiki made.

The calculus of Mungiki, as previously mentioned is to stage very bold and public spectacles in order to align themselves with the power opportunities of the day–but they could not do this without the vast and loyal membership under their command. The conversion to Islam, to force some kind of negotiation with the Moi government, is one example. But we see numerous other examples where the Mungiki allegiance has been contracted, mainly for the benefit of its leaders. Mungiki, it seems, is therefore a complex organization that attempts to satisfy and empower some of the most marginalized members of Kenyan society while simultaneously generating incredible wealth for the leadership. This form of social contract offers a compelling inroad to the study of human rights, where the machinery that orchestrates numerous projects addressing social and economic rights is the same machinery disempowering and alienating citizens.