Declan Galvin

United States International University

Kenya

The history of independent Kenya, not dissimilar to other countries in the developing world, has proven to be complex and often times misunderstood by outsiders. I vividly remember, during the now notorious 2008 Post Election Violence, the media continuously repeating contrived taglines like, “the once peaceful nation of Kenya has unexpectedly erupted into violence,” or “one of the most stable countries, and a symbol of peace for the continent, has devolved into tribal war amid the contested Presidential elections.” These misleading and devastatingly inaccurate statements by the media would have us believe that Kenya was somehow a beacon of stability, and that we (outsiders) should be shocked by the violence, because there lacked preconditions.

However, this could not be further from the truth as Kenya has had, to say the least, an underwhelming record on promoting human rights. My own personal opinion on the matter is that, despite the fact that the Kenyan state has been dreadfully oppressive since independence, it escaped major criticism because it was allied with the United States and the West throughout the Cold War and proved to be a reliable ally overall. Moreover, we find that numerous NGOs, international organizations, and tourists who visit Kenya; activities which cast Kenya in a positive light as a country both welcoming to visitors and stable.

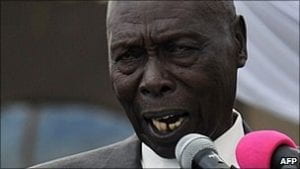

In reality we find that Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, rarely tolerated opposition to himself or his policies throughout the 1960s and 1970s, and routinely assassinated political elites whom he deemed to be a threat. Matters became worse during the reign of Daniel arap Moi, Kenya’s second president, who staved out any sign of opposition by torturing thousands of Kenyans (whether they actually opposed him or not) in the infamous Nyayo House basement chambers, by continuing the use of political assassination instituted under Kenyatta; and later using state auxiliaries to intimidate and kill Kenyans to dissuade them from voting against him during presidential elections in 1992 and 1997. Moi’s tactics allowed him to rule uninterrupted until 2002.

The institutionalization of violence finally came full circle when, during the 2008 post election violence, regular Kenyan civilians began to plan and carry out violent attacks against ethnic opposition in response to the contested results of that election. This development is important to focus on because it shows how the use of violence, once nothing more than an elite tool, had permeated to grassroots level of society. This grassroots violence marks an escalation, and is quite distinct from previous forms of state sponsored violence including the poll violence in the 1990s.

However, Kenyan society has changed since the apex of Moi’s rule in the late 1980s. Today, we find a class of young Kenyan citizens who are more economically and socially empowered than any other generation since independence. These youth have been inspired by the macabre images of the 2008 post election violence, and have committed themselves to making social changes and reforms in Kenyan society needed to emancipate it from violence and oppression. The aspirations of these youth are beginning to pressure and confront a state which, historically, tortured or ravaged dissenters.

From my observations of a public demonstration (described below) it was clear to me that both civil society activists and the Kenyan state authorities are navigating this new democratic territory—very unsure about how to act, and trying not to rely on the old scripts of violence, detention, and torture by the state officials; or fear, retreat, and silence by members of civil society. Kenyan society, not what it was 25 years ago, is currently recasting itself and negotiating what dissent, democracy, and order behaves like.

On May 14th youth activists staged a demonstration dubbed Occupy Parliament, which began in Uhuru (Swahili for Freedom) Park. These youth, however, are quite different from the youth of previous generations because they are predominantly from middle-class backgrounds (activism in Kenya has traditionally come from poor/marginalized classes) and many of them are employed in the tech and artist communities springing up around Nairobi. The violent events during the 2008 presidential election have motivated these activists, and they have begun to pressure and humiliate the Members of Parliament (MPs) who they view as the major drivers to the social problems plaguing Kenya because of their greed, political manipulation, and corruption. The Occupy Parliament demonstration was organized in response to the MPigs, as they are called, who were trying to increase their salary and for trying to dismantle new provisions in the constitution to prevent such financial abuses (they are already the highest paid MPs/Representatives in the world, including US Congress and UK Parliament).

Hundreds of protesters took to the streets that particular day and we all proceeded from Uhuru Park to Kenya’s parliament, just a short distance away. More than a few people told me, as we were making our way to parliament, that this would never have happened 25 years ago and several people referred or pointed to Nyayo House (which was also not far from parliament) where most of us would have ended up. As previously mentioned Moi had no tolerance for dissention, especially for college-aged youth. The leaders of the demonstration are aware of how democratic space has widened—if only enough to allow the formation of these demonstrations—and are actively trying to push the bounds with the intent to widen civil and activist space in Kenyan politics.

The creativity of these demonstrations illustrates this fact, and was designed to draw in Kenyans who are too fearful to protest. In January of this year a tech-artist community, Pawa254, organized the “Official State Burial” and burned wooden caskets as an effigy for each MP in response to their vote to give themselves massive end of term bonuses. The May 14th demonstration, which I attended, had dozens of pigs trucked in to the parliament gates, and then the leaders dumped gallons of pigs blood into a puddle to represent the blood that MPs spill because of the greed and lack of attention to Kenya’s needs.

It wasn’t long before the Kenyan military were dispatched to fire water cannons, tear gas canisters, and beat hundreds of demonstrators. Civil society groups, and legal associations, have claimed that the police response was not only excessive but a violation of the constitutional rights of the Kenyan demonstrators.

Finding words to explain the excitement, uncertainty, frustration, and fear that Kenya is feeling during this time of transition is difficult to explain. And perhaps, as a foreigner, I am not really the one to characterize this new phenomenon. Nevertheless the shift in Kenya is palatable. The emergence of this class of defiant middle-income youth, convicted in frustrating the efforts of the corrupt elite, is entering into conversation with state authorities and pushing the bounds of acceptable dissent. While the future remains unclear (the youth leaders say that Kenyans are still too fearful to protest), it seems that Kenyans are beginning to wake up and trying to set events in motion to gain greater control of their destinies.