This is the fifth installment of an ongoing series. The previous posts are here: (I), (II), (III), (IV).

Day after day, the new data remain true to the trend that tickled my attention about three weeks ago. That trend makes the progress of the epidemics to appear as a parabola, in a graph that has a logarithmic vertical axis. As I explained here, that’s the same thing as to say that the growth rate of the epidemics decreases linearly in time (“decreases linearly in time” is jargon to say that something declines of the same amount every day). If the trend continues, we’re on track to see zero growth rate within one week, and that would be the peak of the epidemics. Thereafter, inshallah, the growth will become negative, corresponding to a decreasing number of infected.

What’s the cause of the epidemics slow-down?

One possibility is that the epidemics has already involved a large fraction of the population. In that case, just like a fire that has already burned most of the forest, it first slows down, and then becomes extinguished by lack of fuel. Or, in other words: if you are the only person infected in town, any person that comes into contact with you can become infected. But if a large size of the town’s inhabitants are already infected, you’re not likely to contribute much to the contagion: most of the people you’ll meet are already infected!

In past centuries, that’s how most epidemics have ended: because new people to be infected had become scarce. Can it be the case for COVID-19? Apparently, according to some colleagues at the University of Oxford, yes. This article of the Financial Times (no less!) states: “Coronavirus may have infected half of UK population — Oxford study“. Oddly enough, at the time of publication there was absolutely no sign of slow down of the epidemics in the UK, making the Oxford study, and the FT article, more alike to fake news than serious reporting (now somehow acknowledged by a footnote at the end of the article).

But Italy appears to be at a much more developed stage of the epidemics than the UK, and the growth rate, indeed, is slowing down. Therefore, if the number of infected individuals really is underestimated by orders of magnitude, then it’s plausible that the Italian epidemics is slowing down because it’s running out of fuel.

(This scenario definitely has doomsday’s overtones, but, in fact, it is often presented like a blessing: the infected individuals that have not been counted can’t have developed any serious symptoms, or they’d have been recognized. So, the vast majority of COVID-19 infected would be asymptomatic or nearly so, which would make the disease, on average, less lethal than a common flu.)

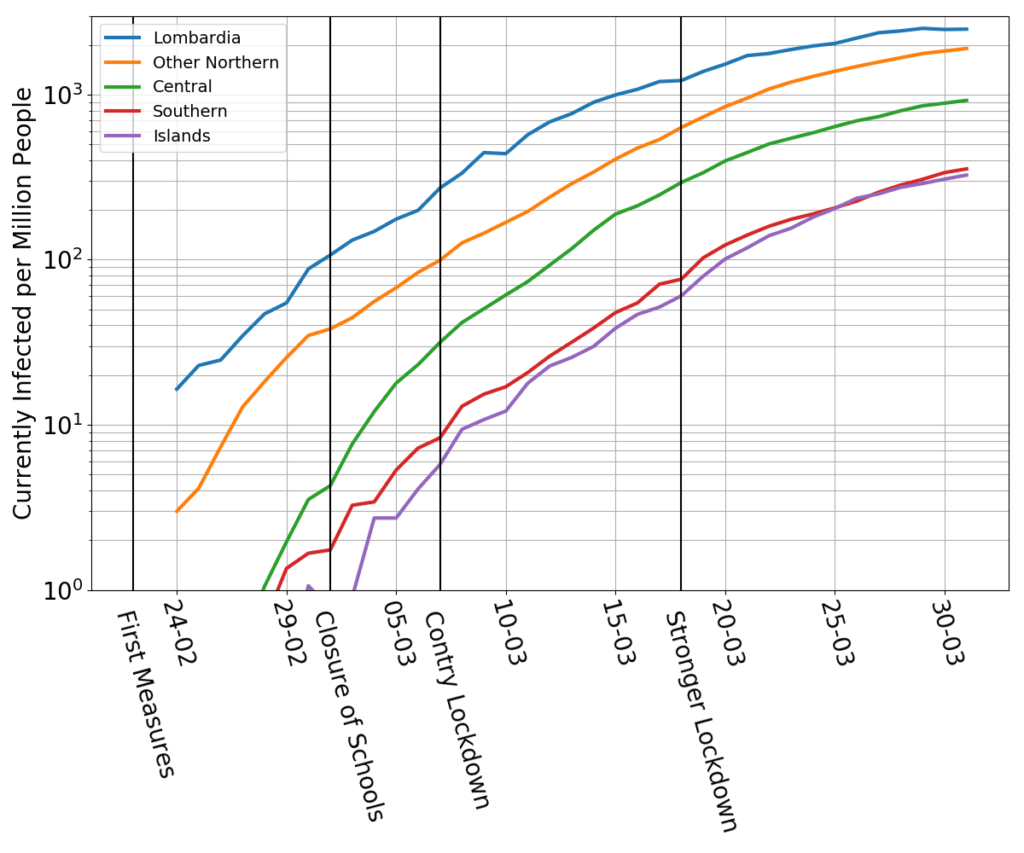

Data, however, tell us otherwise. The following figure shows the fraction of the local population which is officially infected for Lombardia (the most populous region in Italy, and the one that was hit the earliest and the hardest by the epidemics), for the rest of the North, and the Center, South and Islands.

Even if we held that some sort of mechanism massively hampered the recognition of the infected, there’s no reason whatsoever to believe that the misses would occur more frequently in the South than in the North. Thus, looking at the data, we still need to conclude that the North has 10 times more infected per million people than the South and the Islands.

And yet, the curves of North, Center, South and Islands bend in unison. If the slow down of the North were due to the virus running out of new people to infect, the South and the Islands, with a much lower proportion of infected, should have kept growing fast. Instead, they slow down, too.

These data show that the cause of the slow down has acted simultaneously over the entire country, even though the contagion was much more advanced in the North than in the South.

And what then that cause would be? Short of inventing some other conspiratorial fantasy, the obvious conclusion is that the slow down has occurred because of the progressively harsher lockdown measures. In the last 15 days or so, Lombardia has slowed down a bit faster than the rest of the country. In fact, it might be peaking right now. That’s consistent with the harshest measures having been implemented there (and in Veneto, which goes at the same pace as Lombardia, as showed here).

If I’m not fooling myself, then the linear decrease of the growth rate of the epidemics in Italy is due to a progressive crescendo of the lockdown measures. If we had gone suddenly from business as usual to a state of near curfew, the growth rate should have shown a transition between two nearly constant plateaus. Not a sharp transition, though. The disease requires several days to incubate, and this number appears to be highly variable. Lockdown measures may start to curb the growth rate of the disease a few days after their adoption, but their fullest effect would take no less than two weeks to manifest. The transition between a plateau and the next would be a gentle slope. Thus, a sequence of harsher and harsher measures taken at intervals of a week or so, might very well bring about a linear decrease of the growth rate.

And so I conclude contemplating a glass which is half full, and half empty.

It’s half full, because the lockdown is working. Italy’s fight is not in vain. The sacrifices are paying back.

But it’s also half empty. At this stage, which further measures can possibly be taken to reduce even more the growth rate, and take it to negative territory? The country is strained, the economy on the verge of depression. If further sacrifices were required to win the disease, would the country be able to endure them?