The fight against the virus rages on. It’s obvious that the peak won’t be attained in March, but there’s no evidence that it has slipped forward by a humongous amount. The situation is hanging in the balance and uncertainty is still sovereign. Yet there’s still hope for a peak in the first few days of April.

Or there’s is not?

I hoped to gain more information by looking at the regional breakdown of the national data. At the moment of this writing, the situation in Italy is highly inhomogeneous. One of the northern regions, Lombardia, is in truly dire straits. The rest of Northern Italy is not in good shape, either. As you move South, the numbers taper down tremendously, but don’t vanish. This begs the question whether the overall trend is the same over the entire country, or different regions are showing different dynamics.

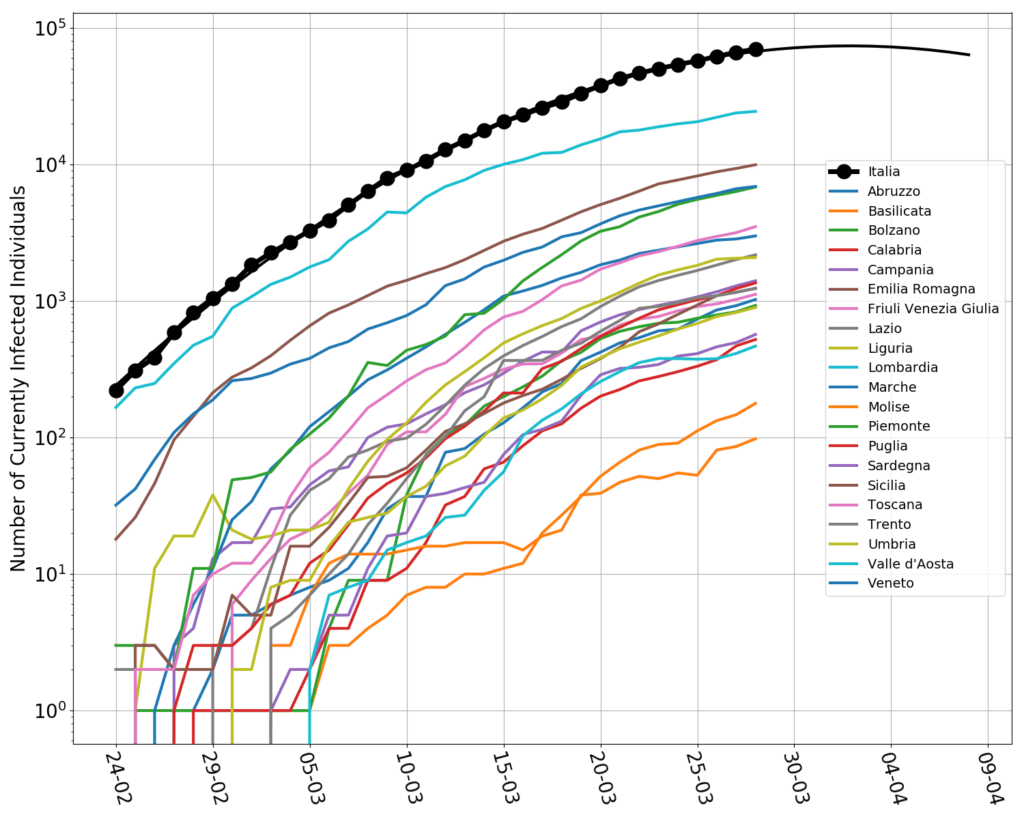

I spent a few minutes weaving together a little python script that reads the regional data by Protezione Civile (here). These are the plots, in log-scale.

Even though I’m Italian, I can’t handle this bunch of jerking spaghetti. There are surely some interesting patterns, but, all together, is too much. In addition, laboratory backlogs and other data processing issues, have created spikes and sudden turns on the curves, making it difficult to distinguish what is real from what is, arguably, an artifact of the data collection process.

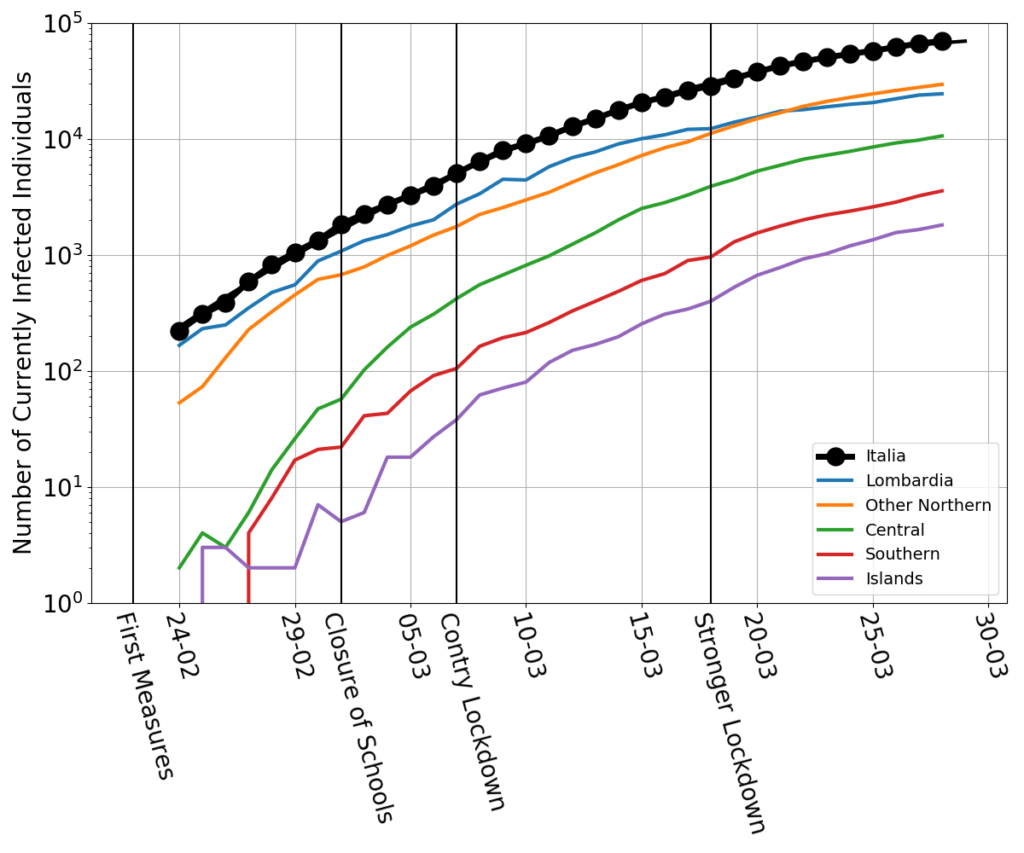

Therefore I have aggregated the data. Lombardia is still kept on its own. The rest of the country is broken down in “Nortern”, “Central”, “Southern”, “Islands”. On the graph, I have also marked the dates of the first lockdown measures, involving only selected municipalities in Lombardia and Veneto, of the closure of all schools and universities, of the country-wide lockdown, and of a further restriction on the citizen’s freedom of movement. (A detailed timeline here.)

The clearest pattern is that Lombardia is, yes, the most affected region, but it is also the one that, since the beginning of the data collection, has slowed down the most. By and large, the other parts of the country have gone along roughly parallel curves. The central part of the country was speeding up the most in the first part of the epidemics. The southern and the islands may possibly have not slowed down as much as the others in the last few days.

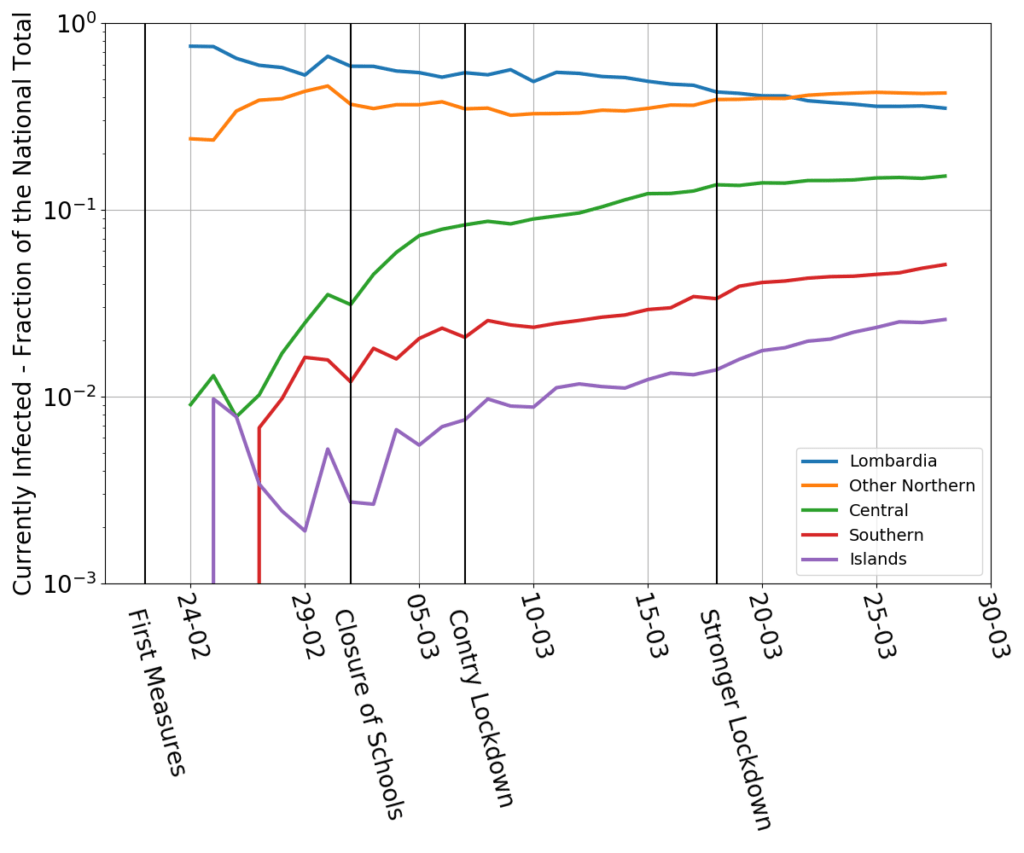

These eyeballed patterns are confirmed by the next graph, which plots the fraction of currently infected individuals with respect to the national total.

Southern Italy and the islands currently have a small minority of the overall infected population (less than 10%, jointly). But their fraction is increasing at a disturbing pace. A vague possibility is that this is a delayed effect of the wave of Southern residents who worked in the North and hurryingly returned South when news of the country-wide lockdown leaked from the government’s offices. After all, if you were a temporary worker subletting a room in Milan, what would you do when your employer shuts down for what may be a long stretch, and simultaneously you hear than you might be stuck for many months, without an income, in a highly expensive city? Parents and grand parents back home may be the only social safety net left…

And this leads to a more general consideration. A country hit by an epidemics is just like a body bitten by a venomous snake. In the absence of an antidote (there’s no vaccine yet) one needs exert pressure to slow down the blood circulation. But that is feasible only up to a point. If not enough blood circulates, any poison damage avoided will be more than compensated by gangrene’s. So, economic measures must go in lockstep with hygienic ones, and are not antithetic to them (as the comments of some brainless pundits and cheeky politicians have sometimes implied on the news). A subsistence salary for anyone who may need it, even (in fact, especially) for those who were undocumented workers, as well as state-granted credit lines for companies, especially tiny ones, may be the most effective way to convince everyone to stay at home.