This is the sixth installment of an ongoing series. The previous posts are here: (I), (II), (III), (IV), (V).

Remember the opening scene of the movie “Gladiator”? The almighty Roman legions unleashing hell over the brutish German tribes, doomed to be vanquished by the unstoppable advancement of civilization?

Hollywood’s baloney!

Ever since Varus lost three legions in Teutoburg’s ambush, almost all the vanquishing and of the pugnacious hell went the other way around. German generals and emperors have often dignified the Peninsula with their awe-inspiring might (and not always for war), hammering down in the minds of the Italian population the notion that German men and women must be some sort of nearly divine entities. (Yes, Frau Bundeskanzlerin, too.)

And if European history is not your forte, just consider that they’ve won as many world cups as we did: they got to be semi-gods!

Of course, I’m not immune to that mindset. Therefore, when I heard a rumor stating that Germans have such a low COVID-19 death count because their genome is different from the rest of the world, making them more COVID-19 resistant, I instinctively told to myself: Of course! How could I have not thought about it? Then I recalled that the last time somebody talked about German’s intrinsic genetic superiority it didn’t bode well for anyone, so I gave myself pause.

I do believe that the notion of Volksgeist (Esprit des nations, if you live west of the Rhine) has some merit. But, as much as cultural and linguistic boundaries may be powerfully sharp (and dangerous fools are those who don’t acknowledge that), their genetic counterpart has to be fuzzy beyond belief, especially in a continent where history has stretched and folded people almost as much as a taffy candy.

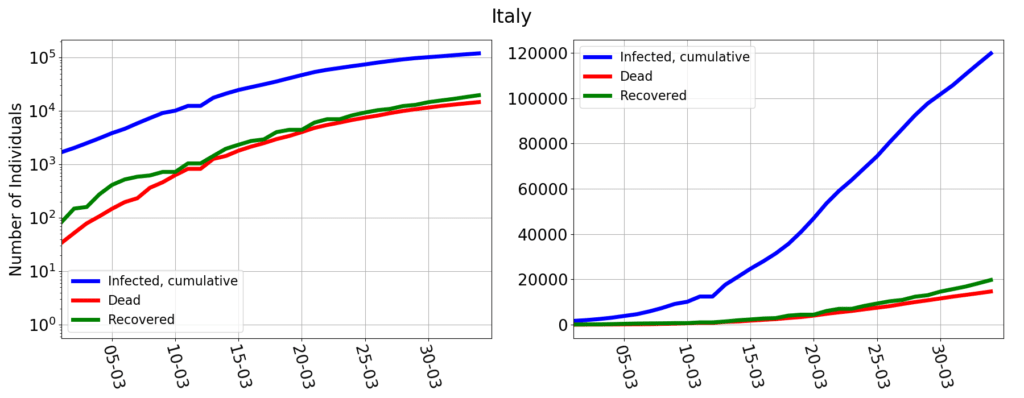

So let me stop blowing hot air balloons, and look hard at the data. Here I’m using the world-wide data collected by Johns Hopkins University. They track the cumulative number of (i) infected individuals, (ii) deceased individuals, (iii) recovered individuals. Their data for Italy is shown in the following figure (the left panel uses a vertical log-scale, the right panel a linear one, but the data is the same in both):

The numbers coincide with those of Protezione Civile (which appears to be Johns Hopkins’ data source for Italy). But they are reported differently: the cumulative number of infected individuals reported by Johns Hopkins (and many other data sources) is not the same as the number of currently infected individuals, reported by Protezione Civile. The relationship is the following:

cumulative infected = currently infected + dead + recovered

For epidemiological analysis, the number that matters is that of the currently infected: only those that are alive and currently have the virus in their body can potentially spread it. But the number that is actually measured is the cumulative infected: one simply counts all those that test positive to the virus. If then one is diligent enough to keep track of the deaths and of the recoveries, then the number of currently infected is easily computed by subtraction.

At the EU level there is a clear and thorough definition of what is a COVID-19 case. Italy follows that. Furthermore, Italy adopts a strict definition of “recovered” patient: one that after having tested positive then tests negative for two times in a row. Finally, Italy tracks all of the deaths of individuals tested positive. According to this criterion, if I tested positive and then I were hit by a bus, I’d still be counted as a COVID-19 death. Which doesn’t make much medical sense, but makes perfect epidemiological sense, because the bus would have forcefully removed me from the pool of those who can spread the infection.

(By the way, I have not been able to find any EU directive on how to count the recovered or the deceased. In fact, data collection and validation, pompously called “epidemic intelligence process”, appears to occur essentially at the national level, and according to national rules).

Anyhow, the Italian data show that the number of resolved cases (recovery + death) is roughly the same as the number of infected of 15 days before. An early assessment by WHO estimated the typical length of the illness to be about two weeks. Thus the data makes sense: those who got infected at day $n$, by day $n+15$ should either have healed or be dead. The scary part is that in Italy deaths are almost as frequent as recoveries. It shouldn’t be this way. The WHO report mentions that “severe” or “critical” cases require three to six weeks “to recover”. Deaths are those who, have been “severe” or “critical” and, unfortunately, didn’t recover. Thus, they should then lag much more than 15 days, if we trust the WHO report. In Italy the median time from the onset of symptoms to death is 10 days, with a strong sensitivity on whether intensive care units were available or not. Either that initial report was overestimating the length of the illness, or this is evidence that the Italian health care system is being overstretched beyond capacity (truth may be a little bit of both).

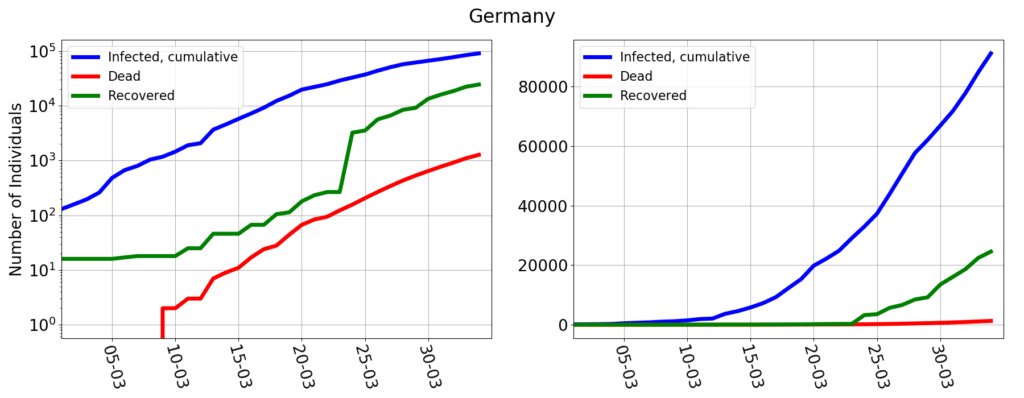

Germany’s data are here:

The number of deaths seems to be lagging that of the infected by almost 25 days (as usual, the log-scale graph gives a better understanding of this kind of dynamics than the usual, linear scale).

Aha!

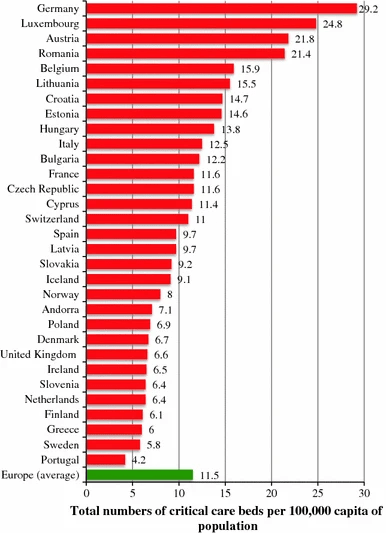

That would make Germany more in like with the WHO estimates and solidifies the idea that high mortality in Italy is a tragic side effect of an undersized healthcare system. After all, Italy’s hospital beds per 1000 people are two and a half less than in Germany. And if one restricts the statistics to intensive care units, the picture doesn’t get any better:

Given the data, it is perfectly possible that the difference between the death rate in Italy and in Germany is solely determined by a more capacious health care system.

But…

But!

What is that sudden spike in the number of recovered between March 23rd and March 24th? Up to March 23rd Germany never had more than 200 recoveries. Then suddenly on March 24th 2837 people healed up (I’m happy for them, but why did they all wait the 24th?). For there on, the number of daily recoveries went onward erratically, with days counting just a few hundred recoveries, and other days with recoveries in the thousands. This is the sort of things that a data analyst has nightmares about: the patterns visible in the data make no sense at all, and yet those are the data written down on the public record.

A data analyst’s memento is that data should never ever be analyzed, unless one is sure of what one is looking at.

Because I wasn’t sure of what I was looking at, I tried to document myself. It appears that COVID-19 data in Germany is gathered and reported by the Robert Koch Institute. I can’t read German (so it’s possible that I have missed something) but they are kind enough to offer some reporting in English. Their latest epidemiological report clearly states that the number of recovered patients is an estimate! The language is quite vague: if somebody was sick before March 22nd and then didn’t report symptoms anymore, then he or she counts as recovered. And yet, not all cases are included in the count, because they “were included in the algorithm only if information on date of symptom onset, symptoms, hospitalisation status and vital status were available“.

Aha!

This is the smoking gun proving that recovery numbers in Italy and in Germany are oranges and apples: you can’t compare them.

What about the deaths? The RKI document is not particularly exhaustive in this respect (I’m sure there’s plenty more information in German, somewhere). It generically speaks of “COVID-19 related deaths“. But what is the relationship? Just having tested positive and then having died makes a relationship exist? Maybe so, but a clearer language would have been appreciated.

The epidemiological document that I have already quoted shows that, in Italy, most of the deceased who had tested positive to COVID-19 where already affected by one or more illnesses. Only in about 3% of the cases the patient was previously perfectly healthy. Most of other cases had serious pre-existing conditions. And this begs the question: if a COVID-19 positive patient with, say, a pre-existing heart disease dies from heart attack, how would that be counted in Germany?

If the Italians had decided to count only the instances where COVID-19 clearly and undoubtedly were the single most important cause of death, then the Italian number of COVID-19 deaths would drop dramatically, possibly reaching German levels, all depending on the exact definition of COVID-19 death that one elects to use.

Lacking a clear definition of what is a “COVID-19 related death“, the suspicion that death numbers of Italy and Germany are also like oranges and apples appears to be more than a wild hypothesis.

(Yes, that was an understatement.) As they say in Rome: “ma de che stamo a parla’?“.

(That idiom on the high table of a Cambridge college would more or less be translated as: “I’m terribly afraid that our debate has been revealed to be utterly moot!“.)

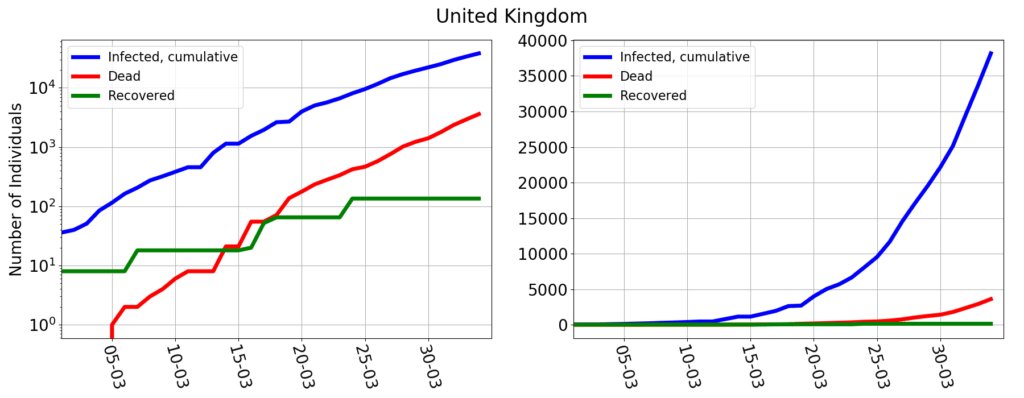

I just mentioned the people who enjoy warm cervisia, (I do, too) which means it’s about time to have a look at the UK data.

In Great Britain the number of those counted as coronavirus deaths lag less than 15 days behind the number of infected, suggesting that the UK health system might be even more overstretched than the Italian one. The official documentation very clearly states that “the figures on deaths relate in almost all cases to patients who have died in hospital and who have tested positive for COVID-19”, but “do not include deaths outside hospital, such as those in care homes”. In summary it’s the same criterion as in Italy, except that they are acknowledging that the count is incomplete. What the UK government doesn’t say (or I was unable to find) is how the recovered are counted. The graph shows a really peculiar pattern, where recoveries occur in jumps, every few days. And in any case, so far, only 135 people would have recovered, on a total of over 47 thousands infected.

Ma de che stamo a parla’?

At the end of this post, if my 24 readers walk away with a clear notion that different countries gather data in different ways, and this hampers a proper analysis of the COVID-19 epidemics beyond the national scale, then I have been successful.

And yet there’s a more important, hidden, overtone. Here I have not done sophisticated mathematical modeling, subtle scientific arguments, or clever deductions. I have just gathered some documents and brought about some questions (yes, let me be clear: I have no clear cut conclusions to offer, just questions). But… shouldn’t be this the job of journalists?

Indeed, the huge discrepancy between Germany’s and Italy’s death count has not gone unnoticed, and a zillion news articles have been written on the topic. Let’s examine the one by the New York Times. On the surface it’s very eloquently written, but upon closer look it reveals to be a mash-up of plausible, but unverified, statements, outlandish theories, and plain falsehood.

Let’s briefly go through some of those:

- The coronavirus in Germany mostly affects the young (which are way more resistant than the elders to COVID-19).

Well, the population pyramid of Italy and Germany are very similar, if anything, Germany has a little more elders than Italy. Then, if really the median age of the German patient is so much lower than elsewhere, I see a question to be asked, not an answer being given: what avoids the contagion to spread to the elderlies? (No sci-fi, please, just reliable data: a speculation is that German’s social structure leads to a higher segregation of elderlies, but without objective data, it’s just hot air.)

- Germany has been testing far more people than most nations.

(The implied explanation being that in other countries there are lots of patients with little or no symptoms that do not get counted.) It’s true that Germany has been testing more than Italy: 918,460 vs 691,461. But that’s not much more. The hypothesis would be believable if the fraction of German patients in serious or critical conditions were much less than elsewhere (for Italy that’s about 22.5%), but that figure is not disclosed. (At least not in RKI’s English documentation, which, however, mentions that 12499 intensive care beds are “occupied”, without clarifying whether it’s all from COVID-19 positives, or other people, too. If it were 12499 COVID-19 patients that would amount to over 15% of the infected…).

- Effective tracking and shut down of at-risk areas (e.g. schools)

If tracking and shut-down were effective in reducing the number of deaths, it could only do so by reducing the number of infected. But that number is still growing at an alarmingly fast pace… In other words, tracking and shut-down may affect the growth of the epidemics, but don’t explain the ratio between the number of infections and deaths.

- More intensive care beds

That is something I could believe, because I’ve been able to substantiate the claim with hard numbers (see above).

- Frau Bundeskanzlerin has thaumaturgic powers

(Yes, no kidding, read the last section.)

It’s a journalist job that of asking questions, read official documents and evidence inconsistencies, ambiguities and shortcomings.

On COVID-19, as that NYT article manifestly shows, journalist are acting just as spin masters. As the crisis rages on, people will ohh and ahh at what they read in the press. But in the long run, it will only take credibility away from any news. And that’s not good.

While collecting material for this post, I have greatly benefited from discussions with my colleagues and friends Luciano Jannelli and Christian Haefke. Of course, all opinions and any mistake is solely mine.