What Does ‘Food Studies’ Mean?

Defining a multidisciplinary domain with keyword bibliometrics

Research in any discipline is challenging to master, but food studies asks inquirers to learn techniques in what might be comparable to staging in multiple restaurants, all at once. Wading through multiple canons and incongruous methodologies is like trying to learn how to make the perfect tagliatelle in a ramen restaurant; everything is there, but you might end up with a different noodle. As a librarian for the field of food studies, I seek to aid, foster, and instruct students and researchers honing their research craft. My research explores the landscape of scholarly food studies itself. I hope that food studies scholars can find some knowledge, learning, and understanding about the complicated task of researching within the field, and that with this project, researchers and students might have a more precise direction and understanding about exercising their skillful craft of research.

Food studies is a multidisciplinary field. This concept, which first gained popularity among science-ethicists in the 1970s, is one of three theoretically cross-disciplinary typologies, which also include interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary (Klein 2010). Whereas transdisciplinarity cuts across fields (like critical theory), and interdisciplinarity seeks to manufacture an entirely new field with aspects of others, according to Klein (2015), multidisciplinary fields are characterized by how they “juxtapose separate disciplinary approaches around a common interest, adding breadth of knowledge and approaches.” Within this category, food studies, therefore, positions food as a common interest around which perspectival frames are attached from established disciplines.

Additionally, as a relatively new field, food studies allows its scholars more freedom than standard disciplines. Its nascence precludes any requisite cannon of materials or a strict oeuvre of methodology. Its diverse objectives and perspectives offer researchers liberty to work amongst numerous lineages of academic thought. This freedom however, and its requisite information organization and discoverability problems cause real-world problems too. Although, as Warren Belasco (2008) claimed, “food studies is now ‘respectable,’ it is also inherently subversive.” In essence, the field runs against academic traditionalism. Because of this, as Bellows, Welsh, Ludden, and Alfaro (2018) show, food studies scholars face difficulties in tenure and promotion processes. Lisa Heldke (2006) warns her students that “you had better be prepared to develop a thick skin.”

For library scientists, the newness and amorphousness of the phrase food studies means there is little guidance on how to best provide research assistance for peer-reviewed food studies journal scholarship. One major exception is Duran and Macdonald’s (2006) highly cited article that gives basic bibliographic recommendations for finding several types of materials. For food studies article research, Duran and MacDonald note that “disciplines may use different terminology to describe the same concept,” further complicated because “any aspect of food studies research there are relevant articles in multiple disciplines,” and thus multiple vocabularies. Their solution, to “explore the literature by using indexes for a variety of fields” is incomplete. To what degree is the scholarly food studies landscape fragmented by diffuse vocabulary? Is this a necessary function of food studies research? Addressing these challenges, this paper offers an answer to a simple question: what does the phrase “food studies” mean in scholarly article research?

Background, motivation, and The “Food Studies” Corpus

Food studies departments, faculty members, researchers, and students produce an enormous amount of published academic content each year. However, to many of these authors relevance to food studies seems secondary: food anthropology scholarship is primarily published in anthropology journals; agricultural economics work is primarily published in economic journals. Food studies scholars even tend not to self-identify their food studies scholarship, preferring instead, their primary discipline’s subject-specific vocabulary. As a result, food studies’ information domain is fractured; a shapeless amalgam of sub-disciplinary silos. No single or canonical forum (platform, database, website) exists for scholarly food studies conversations. This lack of cohesion frustrates many in the field (Nestle and McIntosh 2010; Hamada et al. 2015) and makes the bar for entry high (Korr and Broussard 2005). Due to food studies’ multidisciplinarity, it is possible that no comprehensive database could ever exist. All cross disciplinary domains have imprecise limits and suffer from disciplinary isolation. a But this predisposes the field to what Marcia Bates (1996) described as “cynosure of an extensive social and documentary infrastructure [in which] academic fields develop a common vocabulary and research style.” Without a common language, food studies scholars “tend to overlook materials that are published in other fields,” (Duran and MacDonald 2015).

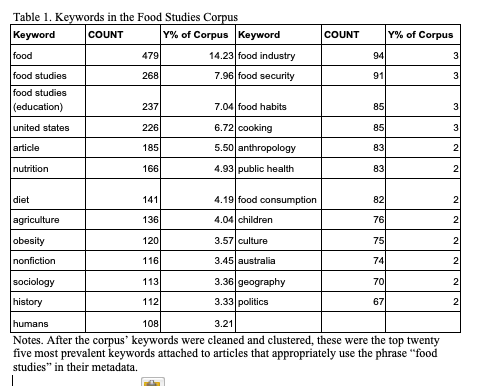

My work introduces a dataset of citations, The “Food Studies” Corpus, that may be able to help marshal cohesion among food studies’ diffuse vocabulary (Malin 2020). The corpus contains 3,365 articles and their metadata were gathered and synthesized from five general bibliographic databases, using scoping review methodology. The following shows the top 25 keywords contained in the corpus, as well as their percent of the corpus. The wide variation in the topics conveyed by these keywords indicates the broad range of food studies, covering food, agriculture, nutrition, diet in addition to keywords reflecting disciplines such as history, sociology, anthropology, and geography.

The keyword metadata was then enumerated with text frequency analysis. Finally, I used bibliometric mapping software to cluster keywords into subdisciplines. Perhaps this set of words, mapped to their disciplinary context, will allow scholars to frame concepts with more cohesive words, and allow students the ability to research with less difficulty.

Conclusions

No matter the subject, there is always some degree of linguistic disconnect between the words scholars choose to write with and the words researchers choose to search. This disconnect is a universal plight in all disciplines. It is a difficult hurdle for all researchers to address, but comfort with navigating a field’s particular keywords is a signifier of academic mastery and experience. Akin to how one’s knife skills or sauce technique may give information on whether you studied cooking in a French or Italian kitchen, keywords contain semiotic dichotomies; they denotate a concept while connotating a descriptive discipline, methodology, canon, etc.

I believe that it would be most suitable for all food studies scholars to simply self-identify. I recommend that scholars not be afraid to use the phrase “food studies” somewhere in the title, abstract, or author-supplied keywords in their next papers. It will increase discoverability, sensibility, and, most of all, cohesion for the field.

References

Bates, Marcia J. 1996. “Learning About the Information Seeking of Interdisciplinary Scholars and Students.” Library Trends 45 (2): 155–64.

Belasco, Warren James. 2008. Food: The Key Concepts. The Key Concepts. Oxford ; New York: Berg.

Bellows, Anne, Rick Welsh, Maize Ludden, and Briana Alfaro. 2018. “Promotion and Tenure, Journals, and Impact Factor in the Field of Food Studies: Results from May 2017 Qualtrics Survey.” Association for the Study of Food and Society. Food-culture.org.

Duran, Nancy, and Karen MacDonald. 2006. “Information Sources for Food Studies Research.” Food, Culture & Society 9 (2): 233–43. https://doi.org/10.2752/155280106778606080.

Hamada, Shingo, Richard Wilk, Amanda Logan, Sara Minard, and Amy Trubek. 2015. “The Future of Food Studies.” Food, Culture & Society 18 (1): 167–86. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174415X14101814953846.

Heldke, Lisa. 2006. “The Unexamined Meal Is Not Worth Eating: Or, Why and How Philosophers (Might/Could/Do) Study Food.” Food, Culture & Society 9 (2): 201–19. https://doi.org/10.2752/155280106778606035.

Klein, Julie T., and Carl Mitcham. 2010. “A Taxonomy of Interdisciplinarity.” In The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity, edited by Robert Frodeman, 15–30. New York: Oxford University Press.

Klein, Julie T. 2015. “Interdisciplinarity and Collaboration.” In Ethics, Science, Technology, and Engineering: A Global Resource, edited by J. Britt Holbrook and Carl Mitcham, 2. ed, 576–78. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Gale, Cengage Learning/Macmillan Reference USA.

Korr, Jeremy L., and Christine Broussard. 2004. “Challenges in the Interdisciplinary Teaching of Food and Foodways.” Food, Culture & Society 7 (2): 147–59. https://doi.org/10.2752/155280104786577941.

Malin, James E. 2020. “The ‘Food Studies’ Corpus.” OSF. March 30. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DV57F

Nestle, Marion, and W. Alex McIntosh. 2010. “Writing the Food Studies Movement.” Food, Culture & Society 13 (2): 159–79. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174410X12633934462999.