A Landscape of Food Sovereignty in the United States

The concept of food sovereignty was introduced by the international peasant movement, Via Campesina at the 1996 World Food Summit. Emphasizing the right to sufficient, healthy, culturally appropriate food that is produced locally and sustainably, many communities have since worked to control their own food systems (Declaration of Nyéléni, 2007). Food sovereignty has responded to forces of oppression and inequality that extend beyond food access, encompassing the rights of food producers, environmentalism and struggles toward racial, economic, and gender justice (Levkoe, Brem-Wilson, & Anderson).

Despite these common values underlying food sovereignty efforts, local power structures and histories impact the forms these actions take. In the United States, food has been central to resistance efforts around race, land, immigrant rights, and indigenous rights for decades. The food sovereignty efforts are not separate from these. Rather they draw on and are influenced by this broad foundation of U.S.-based movements, resulting in food sovereignty efforts with different foci and approaches (Shawki, 2012; Brent, Schiavoni, & Alonso-Fradejas, 2015).

In 2010, dozens of U.S. organizations sought to recognize this diversity while at the same time, join forces to build a domestic food sovereignty movement. Ranging from grassroots support organizations to coalitions of urban farms and fishers, these groups formed the U.S. Food Sovereignty Alliance (USFSA) (Holt-Gimenez & Shattuck, 2011).

To date, food sovereignty literature in the U.S. has taken two directions – case studies and a broader approach of developing a common framework for food sovereignty. A large number of case studies examine specific sites of food sovereignty, such as food access initiatives in Chicago (Block, Chavez, & Ramirez, 2011), food sovereignty laws in Maine (Kurtz, 2015), and tribal sovereignty in Oklahoma (Mihesuah, 2017). A smaller body of work by scholars such as Brent et. al (2015) identify the USFSA, which works to create a common framework for diverse local organizations, as a site of convergence to come together and work toward food sovereignty.

As of yet, relatively little research has provided an overview of these individual food sovereignty efforts in the U.S.. But, as (Clendenning and Dressler (2013) argue, these local and regional efforts as they may become building blocks of the food sovereignty movement as a whole. And, as Shattuck et al. (2015) note, it is important to understand the particularities of food sovereignty efforts to understand the movement as a whole. This study therefore aims to fill in this knowledge gap, and allow us to better understand the landscape of ongoing food sovereignty efforts in the U.S.

Methods

To better understand food sovereignty in the United States, a mixed methods study was conducted. Primary data was collected between October 2019 and February 2020, through a nationwide survey of English-speaking adults who self-identify as engaging in food sovereignty work and semi-structured interviews with random sample from this same group. The survey comprised 23 questions, which asked about the location and size of their organization, emphasis of food sovereignty projects, challenges the organization faces, and its participation in broader networks. Open ended questions were included to collect information on their organization or project’s structure and mission, the impetus for working in their current field, and the connection between identity and their work. Thirteen semi-structured interviews were then conducted with a randomly selected sample of willing survey respondents to gain greater clarity on their perceptions of food sovereignty, the current state of the movement, challenges in their work, and the support that is available or desired in the food sovereignty movement.

Results: Food Sovereignty Now and Looking Forward

What Kinds of Organizations Work in Food Sovereignty?

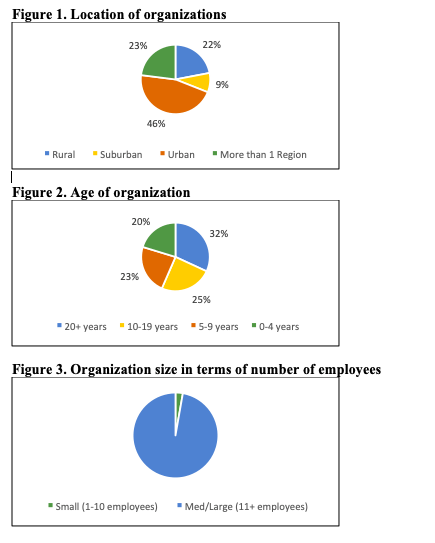

In total, 79 people from 75 different organizations responded to the survey. These organizations vary by size, location, and sector but certain trends were notable. As summarized in Figures 1-3, many organizations are comprised of small teams, nearly half focus exclusively on urban areas and many were founded in the last decade.

Emphasizing the Right to Food and Education

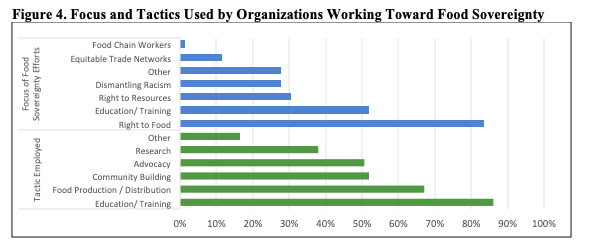

While there are several different aspects of food sovereignty, the two most commonly emphasized were the right to food and education and/or training (Figure 4). Most respondents reported that their organizations focused on what might be considered the core of food sovereignty: ensuring that everyone has access to food that is healthy, sustainably grown, and culturally appropriate. This finding also extends to the tactics organizations use in their work. While not all of the organizations that emphasize the right to food engage in food production or distribution, over half do. Even more engage in some form of education or training.

Dismantling Racism in the Food System

Size, age, and region tended not to impact the focus of food sovereignty efforts and the tactics employed. The most notable exception was found in an analysis of the organizations that focused their food sovereignty efforts on dismantling racism in the food system. Just 6 percent of participants in rural organizations compared to over 40 percent of participants in suburban and urban organizations make this a primary focus of their work. Additionally, while 36 percent of participants working for small organizations report that this is an important focus of food sovereignty work, only 5 percent in medium to large organizations reported the same.

Who Is Working Toward Food Sovereignty?

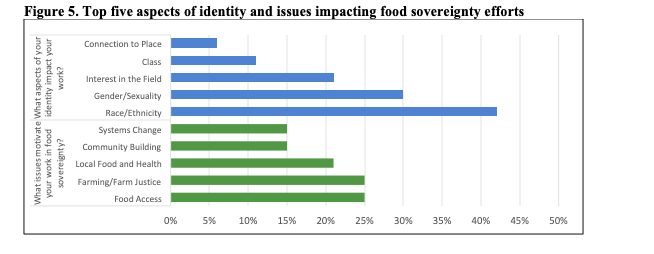

People working in food sovereignty come from a range of backgrounds, and their motivations for entering this field is varied, reflecting food sovereignty’s intersection with many other forms of social justice. Of the 53 people who provided details on their relationship to this field of work, interests mentions most often concerned farming/farm justice and increasing food access. In the former group, some were passionate about the act of growing food, while others came from generations of farmers and witnessed the farm crisis of the 1980s. In the latter group, respondents cited the need to expand fresh, healthy food to larger populations and their desire to become involved in this work (Figure 5).

Respondents also reported that their identity influences their work in this field. Though identity was interpreted in different ways, more than half specified that their race, ethnicity, class, age, or gender identity impacted their relationship to their work. Half of this group acknowledged that one or more of these aspects of their identity affords them the privilege to carry out this food sovereignty work. Others in this group noted that one or more of these aspects of their identity heightened their awareness of inequality in the food system.

Future of the Movement

Most organizations that responded to the survey currently focus on education and obtaining access to sustainable and culturally appropriate food. Those interviewed were able to provide more detail, and when asked about what they hope to see more of in the future of the U.S. food sovereignty efforts, they focused more broadly on the movement as a whole in two primary ways: addressing inequality and improving collaboration among entities working in food sovereignty.

Many indicated the need to continue focus on issues of inequality in the food system. While one noted that racial justice, for example, has become more prominent in food sovereignty discussions, he hopes to see this lead to concrete change and does not become “just another box to check,” an employee of a university extension office said. In the short term, an employee of San Diego’s Health and Human Services Agency noted that organizations must continue shifting away from patriarchal models of support and establish new normal: “[We need] to get beyond that traditional, honestly racist, view of people and give[e] the controls back to the people instead of [treating] them…like…they’re the weak ones.”

Projects need to allow space for voices that are often marginalized, whether this means focusing on client choice in food pantries to mitigate immediate hunger or ensuring community members lead government funded initiatives to strengthen communities. Without this, respondents underscored that long term change will not be possible. An urban farm manager explained this idea as it relates to new leadership: “Women in power, [people of color] in power, young people in power…that’s a big thing. And if it’s not at the center of the food sovereignty movement, I think that we’re going to find ourselves, in another generation, at this same point with the same amount of failure.”

Finally, respondents underscored the importance of collaboration and the need to move beyond the work of individual projects. The same farm manager commented that “there’s a lot of people doing this work. The issue is that…everybody is working in their own camps.” But, he said, “if we don’t zoom out…that’s how we stay divided…Mutual collaboration leads to mutual success.” Another respondent, a university professor, also noted that such collaboration aids in progress toward food sovereignty by addressing past wrongs: “We’re acknowledging [the history of this land] and these connections… and so this is a way that there’s some reconciliation, having the farmers working with the tribes on wild rice restoration and things like this.”

Conclusion

This study offers a view of the respondent organizations and people who are working toward food sovereignty on community, state and national levels, and contributes to an understanding of where organizations are and highlights desired paths forward. My work illuminates that, from urban areas to rural, well established organizations to those just a few years old, non-profits to university extension offices, organizations are working to build communities that have access to and control over the production of healthy, culturally appropriate, sustainably grown food. These organizations often distribute food and engage in education or training, and many support food sovereignty in other ways. The individuals within these organizations also bring with them with diverse interests and backgrounds, spurred by concerns such as food access, community resilience, and farm justice. The findings of my research point to a future where food sovereignty organizations place a greater emphasis on dismantling of oppressive systems and collaboration across organizations.

Download a PDF of the project poster: Seeley_Capstone Poster v1

Human Subjects and Ethical Considerations

This project was approved by NYU’s Institutional Review Board, as project number IRB-FY2020-3847.

References

Block, D.R., Chavez, N., Allen, E. & Ramirez, D. (2011). “Food sovereignty, urban food access, and food activism: contemplating the connections through examples from Chicago.” Agriculture and Human Values, 29, 203-215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-011-9336-8

Brent, Z.B., Schiavoni, C.M., & Alonso-Fradejas, A. (2015). “Contextualising food sovereignty: the politics of convergence among movements in the USA.” Third World Quarterly, 36(3), 618–635. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1023570

Clendenning, J., & Dressler, W. (2013). “Food Sovereignty: A Critical Dialogue,” International Conference Yale University, 1-31. https://www.iss.nl/sites/corporate/files/48_Clendenning_2013.pdf

Nyéléni Declaration. (2007). Declaration of Nyéléni. Nyéléni Village, Sélingué, Mali. Accessed March 10, 2020. https://nyeleni.org/spip.php?article290

Holt-Gimenez, E. & Shattuck, A. (2011). “Food crises, food regimes and food movements: rumblings of reform or tides of transformation?” Journal of Peasant Studies, 38(1), 109-144. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2010.538578

Levkoe C.Z., Brem-Wilson, J. & Anderson C.R. (2019). “People, power, change: three pillars of a food sovereignty research praxis.” Journal of Peasant Studies, 46(7), 1389-1412. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2018.1512488

Mihesuah, D. (2017). “Searching for Haknip Achukma (Good Health): Challenges to Food Sovereignty Initiatives in Oklahoma.” American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 41(3), 9-30. https://doi.org/10.17953/aicrj.41.3.mihesuah

Kurtz, H.E. (2015). “Scaling Food Sovereignty: Biopolitics and the Struggle for Local Control of Farm Food in Rural Maine.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 105(4), 859-873. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2015.1022127

Shattuck A., Schiavoni C.M., & Vangelder, Z. et al. (2015). “Translating the Politics of Food Sovereignty: Digging into Contradictions, Uncovering New Dimensions.” Globalizations, 12(4), 421-433. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2015.1041243

Shawki, N. (2012). “The 2008 Food Crisis as a Critical Event for the Food Sovereignty and Food Justice Movements.” International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food, 19(3), 423-444. http://search.ebscohost.com.proxy.library.nyu.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=91516736&site=eds-live.