Meat From Muscle Grown in a Lab? Consumer Perceptions of Cellular Agriculture

Cellular agriculture, commonly referred to as ‘cell ag,’ and referred to in this research as “lab-grown meat” and “cell-based meat” is a relatively new technology that produces meat for human consumption without the raising and slaughtering of animals. The process begins by obtaining cell cultures of muscle tissues from living animals, and then growing these cells in a laboratory setting into fully developed muscle tissues. This application of tissue engineering produces meat that is the same as or similar to traditional meat in its composition, taste, texture, smell, and nutritional content (USDA, 2018).

Several companies are currently producing lab-grown meat in the United States. However, their cell ag meat is not yet available for purchase by consumers. Debates on agency control over lab-grown foods, including input from USDA and FDA, have delayed cell-based meat’s arrival on grocery store shelves, some lab-based meat companies indicated they are preparing for mass-production and sale of their products. One particularly large and well-funded cell-based meat company, Memphis Meats, has raised $161 million for a production facility in California and is working closely with USDA and FDA to ensure product safety before it comes to market (Memphis Meats, 2020). The goal of this research is to better understand the way potential consumers react to producing meat via cellular agriculture and if they would consume cell-based meat products.

Methods and Description of Respondents

To address these questions, I developed a mixed methods study, consisting of a survey and interviews. The survey was administered via Qualtrics between December 1, 2019 and February 29, 2020. Responses were solicited using the method of snowball sampling, which relies on social networks for dissemination; links to the survey were sent out via email and on social media including Facebook and Instagram. The survey was completely filled out by 204 individuals.

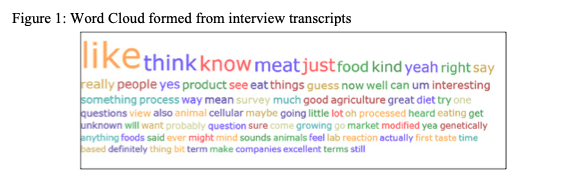

The final question of the survey collected emails of those willing to be interviewed. Interviews were conducted to gain a deeper understanding of how consumers view and pose questions about cellular agriculture products. Of those who responded affirmatively, 20 submitted the required interview consent form and were then interviewed over the phone or via Zoom video call. The audio of all interviews was recorded and transcribed using Otter.ai. One audio file was inaudible and could not be transcribed, and thus was omitted from the analysis; a total of 19 interviews form the basis of the analysis. Using the qualitative data analysis software Atlas.ti, the interview transcripts were analyzed to create a word cloud in order to identify commonly used words. Finally, subjective analysis of respondent’s tones and intonations during their interview was used to gauge their overall opinion of cell-based meats.

About half of respondents were between the ages of 18 and 27, and one quarter of respondents between the ages of 28 and 37, and one quarter were between 37 and 83 years old. About 75% of respondents were female, 80% were omnivore (eat all meat and vegetables) and 90% had a college or graduate-level education.

The survey contained questions regarding participants’ knowledge and awareness of cell-based meats, their level of understanding about a given definition of cell ag products and the process behind creating them, their willingness to eat or try cell ag meats, and their overall opinion of cellular agriculture. The survey also included questions regarding participant’s demographics such as age, gender, and education level. The survey had one open-ended question where participants could type out any opinions they had about cell-based meats. The interview was designed to ask similar questions, but also included prompts for participants to describe why or how they formed their opinions, including the thought process behind their reaction to cell-based meats. Themes identified from the answers to the open-ended question of the survey as well as from the interviews were based on words chosen by those interviewed and the tone they used when speaking. The themes reveal differences in certainty toward accepting the product, curiosity about cell ag meat, and confidence in which they spoke about the cell ag meat.

Word choices reveal differences in acceptance of cellular agriculture

There were common themes shared between the open-ended question of the survey and the interviews that indicated participant’s acceptance or rejection of cell based meat. I organized themes into 6 major categories:

- Impact of cell ag products on consumers (price/cost, health effects/nutrition, additives such as antibiotics, taste)

- Impact of cell ag products on producers and the market (marketing/labeling, fair competition to traditional meat and plant-based products, livelihoods of farmers)

- Impact on environment (natural resources, animal welfare, animal agriculture, global warming, sustainability)

- Government regulation

- Technology

- Validity and value (the worthwhileness of cell ag as a means to produce food)

The most commonly used words in interviews were also analyzed. Figure 1 is a word cloud created using Atlas.ti that shows the most commonly used words across 19 interviews, with a minimum occurrence of 54 times to be included in the word cloud (54 is the lowest-occurring interval option in the Atlas.ti software.). The words “think,” “know” and “like” were the most commonly used words across the interviews. It should be noted that “like” is a common verbal tic used in everyday conversation, and while it can indicate uncertainty it does not always do so. In the context of these interviews, “think” and “know” show the dichotomy between certainty (I know) and uncertainty (I think), and that uncertainty was more prevalent than certainty. The fillers “like” “uh” “um” and “hmm” all indicated either uncertainty or reflection before or while a respondent spoke.

Differences in curiosity regarding cellular agriculture

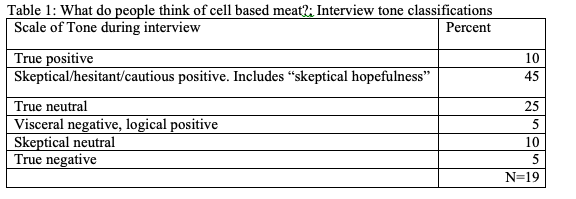

Some overarching themes in tone revealed uncertainty, curiosity, neutrality, and desire for more information about cellular agriculture. In addition to commonly used words and phrases, tone, intonation, and pauses were also analyzed. I found that speakers often used uptalk, also known as upspeak or HRT (high rise/rising tone/tune/terminal). Uptalk is “a marked rising intonation pattern found at the ends of intonation units realised on declarative utterances, and which serves primarily to check comprehension or to seek feedback.” (Foulkes, 2018) The effect or interpretation of uptalk in a conversation is often dependent on those who take part in the dialogue. It is often perceived as indicating a question, doubt, or uncertainty of the speaker, however this is not always true. In the context of my interviews, uptalk, when paired with definitive statements (meaning terms that typically indicate an assured, convinced, or definitive answer) like “yes” and “no,” can be interpreted to serve several purposes for the speaker: (i) seek validation for an answer (ii) indicate their thought process is not finished, or (iii) a desire to continue the dialogue with or obtain more information from the interviewer. I interpreted uptalk as uncertainty either in the speaker’s response or toward cellular agriculture overall. This led to me to create classifications of tone and how it related to the respondents true view of cell-based meats, shown in Table 1.

Pauses: Pensive or stream of consciousness?

The analysis of when or how long people paused while answering a question revealed two types of speakers: 1) pensive and 2) stream of consciousness. Pensive speakers tended to pause before and during their answers, as if to gather their thoughts before speaking, while stream of consciousness speakers rarely paused and instead vocalized their entire thought process before reaching an answer. Stream of conscious speakers might also pause before or during an answer, but seemed to think aloud and change their word choice more often than pensive speakers who seemed to choose their words more actively before speaking. Both types of speakers used fillers such as “uh” “um” “hmm” and “like.”

Discussion and conclusion

Overall, nearly 70 percent of those interviewed had a neutral stance regarding cell-based meats. At the same time, there was a wide range of emotional and logical reactions, leading many to adopt a “wait and see” attitude. Most did not resist cell-based meats coming to market, but at the same time did not want to be among the first to eat or try the product, usually out of fear of unknown long-term health consequences. Others were willing but not committed to trying cell-based meat, usually out of curiosity, shown by the frequency of the use of the words “maybe” in the word cloud (figure 1). The overall uncertainty and neutral opinion toward cell-based meat found based on tone and word choice in this project suggests that consumer education, company transparency, and product comparability to traditional meat in regard to cost, taste, nutrition, and long-term health effects will be the most important factors in determining the success of cell-based meat to make it from laboratory to grocery store and finally on to the plates of consumers at home.

Sources

Foulkes, Paul. “Uptalk: The Phenomenon of Rising Intonation.” Journal of Sociolinguistics, vol. 22, no. 1, Feb. 2018, pp. 129–134. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1111/josl.12266.

Memphis, Meats. “Memphis Meats Raises $161M for Cell-Grown Meat Plant.” Food Manufacturing, 24 Jan. 2020, www.foodmanufacturing.com/capital-investment/news/21112037/memphis-meats-raises-161m-for-cellgrown-meat-plant.

USDA. “Joint Public Meeting on the Use of Cell Culture Technology To Develop Products Derived From Livestock and Poultry.” Federal Register83, no. 178 (September 13, 2018): 46476–78. https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2018-19907.