Front matter. In book publishing, it’s the stuff that comes before the page with the Arabic numeral 1, the elements given those quaint lower-case roman numerals: the title page, colophon (metadata such as the copyright notice, edition, name of the typeface, printer, etc.), dedication, acknowledgments, table of contents, list of illustrations, foreword, preface, and such. What’s the equivalent of front matter for an archival motion-picture film?

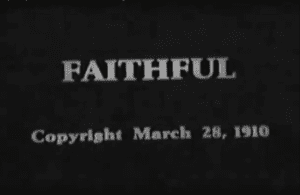

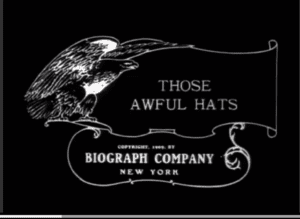

In looking at the digital video reproductions of pre-1918 motion pictures (scanned 16mm films, 35mm films, and paper prints) that LOC provided for this MEP project, we see a gallimaufry of short shots and flash frames preceding the head title (if one exists) or the first shot of the work.

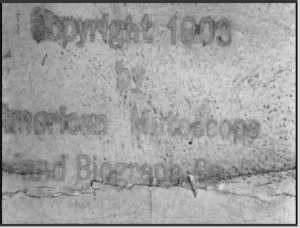

The print medium analogies for early cinema were in use from the beginning of film preservation. Howard Walls’s May 6, 1943 presentation to the Society of Motion Picture Engineers technical conference, announcing the work on the Paper Print Collection, was entitled “Motion Picture Incunabula in the Library of Congress,” incunabula being texts printed before 1501, when the printing press was new. [See Journal of SMPE no. 42 (1944): 155-159.]

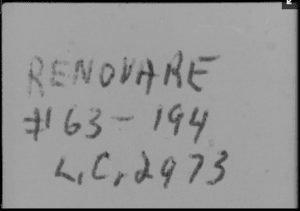

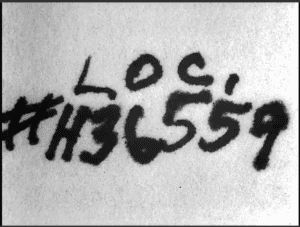

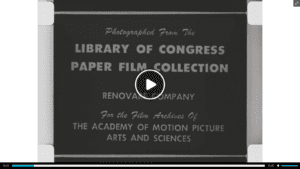

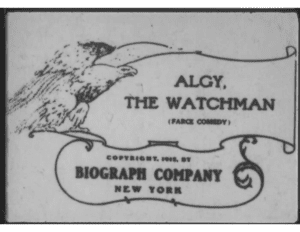

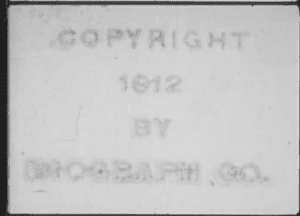

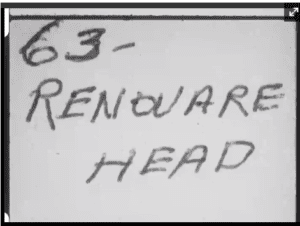

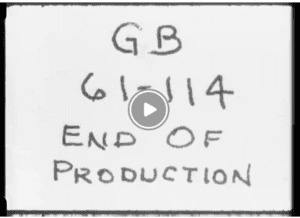

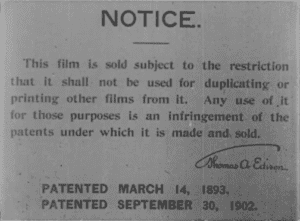

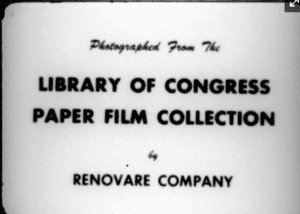

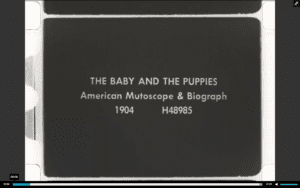

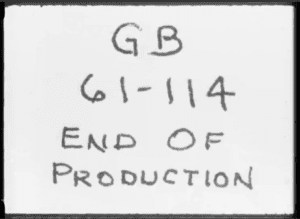

Below is a selection of frames that appear at the beginning (mostly) of some of the movies that participants in the project are studying. Some are from archival interventions that appear in the middle of the original film, such as the textual indicators the preservationists at Kemp Niver’s Renovare Company inserted when an intertitle was missing from a paper print. (In printing-press terms, we might call this a “slug,” i.e., a “usually temporary type line serving to instruct or identify,” per M-W.com.) Most are from films in the Paper Print Collection, others are from LOC’s George Kleine Collection (catalog for the latter here.). Others are from unidentified elsewheres. Except where a researcher has imported a movie from a site such as the Internet Archive or YouTube, movie files were created by the Library of Congress and delivered to the Media Ecology Project for hosting.

An odd anomaly:

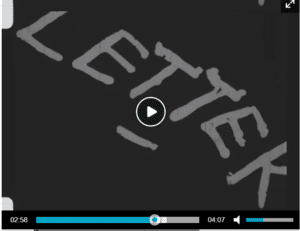

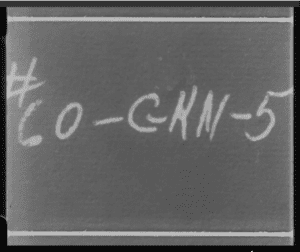

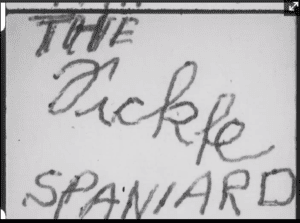

While converting the Library of Congress paper print collection of early motion pictures into 16mm film, the technicians often added a quickly written head title or identifying text. The Fickle Spaniard (Biograph, 1912) has a handwritten title, but in an extremely unusual instance the letters are animated. The operator of the Renovare machine in 1963 would have had to slow the normal work flow to write the unfolding title on a few dozen frames to get this 2 or 3 seconds of animation. Coming as it does as a surprise in the midst of all the paper print films, it has an uncanny effect, especially because it is reminiscent of the scratched-on titles and signatures that Stan Brakhage and other avant garde filmmakers were doing circa 1963. (Downloadable here: The Fickle Spaniard — animated title.)

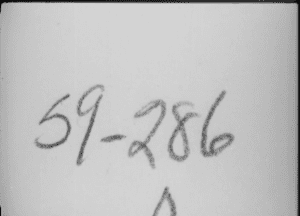

Looking again at the frames that include identifying numbers from LOC films — e.g., #63-194, 59-220, #60-GKN-5, etc. — it seems likely that the first two digits denote the year in which Renovare or LOC copied work to 16mm film masters. In the case of GKNs — George Kleine nitrate — it was the U.S. Department of Agriculture film laboratory that copied the Kleine 35mm nitrate to 16mm film for the Library in 1960. As was standard operating procedure at the time, the potentially hazardous and flammable nitrate cellulose was destroyed after it was preserved on 16mm. Also, the Library had inadequate nitrate film storage space at the time. (Now it has state of the art vaults in Culpeper, Virginia.)

A last point to note: on preservation titles added by Niver’s Renovare (and originally Primrose) team on behalf of the Library and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, what is now officially known as the Library of Congress Paper Print Collection is identified as the “Paper Film Collection.” A bit of an oxymoron, paper film.

§ § § §