In the previous post, we examined the films featuring performer Kathryn Osterman (1883-1956) at the American Mutoscope & Biograph Company, starting with The Rose (1903), considering it as a precursor to the Edison company’s popular novelty film Three American Beauties (1906). This follow-up post points to some related primary research resources, motion picture catalogs. It also considers a contemporary figure with similar appeal, Anna Held (1872-1918), who also appeared in AM&B films. Held, the common-law partner of Florenz Ziegfeld, enjoyed much greater celebrity than Osterman. Although Luise Rainer won an Academy Award portraying the actress in The Great Ziegfeld (1936), Held is not widely remembered today.

First, here’s a copy of one of her two appearances before the Biograph on May 24, 1901. Although the copyright record refers only to one title (simply Anna Held) AM&B’s catalog lists no. 1864 Anna Held (Full Length) and no. 1863 Anna Held (Bust View). The latter is found on the websites of three stock footage companies, and perhaps nowhere else on line until LOC provided an MOV for our NYU class and the Media Ecology Project. To embed it here I put it in the Internet Archive, Orphan Film Symposium Collection.

Filmed in 68mm by Frederick S. Armitage.

AM&B’s Picture Catalogue of 1902 pitched it as “A stunning picture of the well-known actress in the drinking scene which made such a hit in Papa’s Wife. The figure is shown in bust view, making the head very large and giving a clear view of the facial expressions of the beautiful artiste.” The company said that both “make hits either in the Biograph [35mm projection service] or Mutoscope” [hand-cranked peep-show viewer]. The production log says Anna Held No. 1, Full Length was sold in lengths of 91 feet and 532 feet; Anna Held No. 2, Bust, 59 and 340 feet. The shorter lengths would’ve run under a minute and likely were the frames printed onto mutoscope cards. The longer rolls we can only speculate about: were multiple or longer takes of the same composition shot? Did the 532-feet item include both films edited together?

The comedy Papa’s Wife was a popular success from 1899 to 1901, with Act 2 featuring naif Anna getting tipsy on her first champagne and singing.

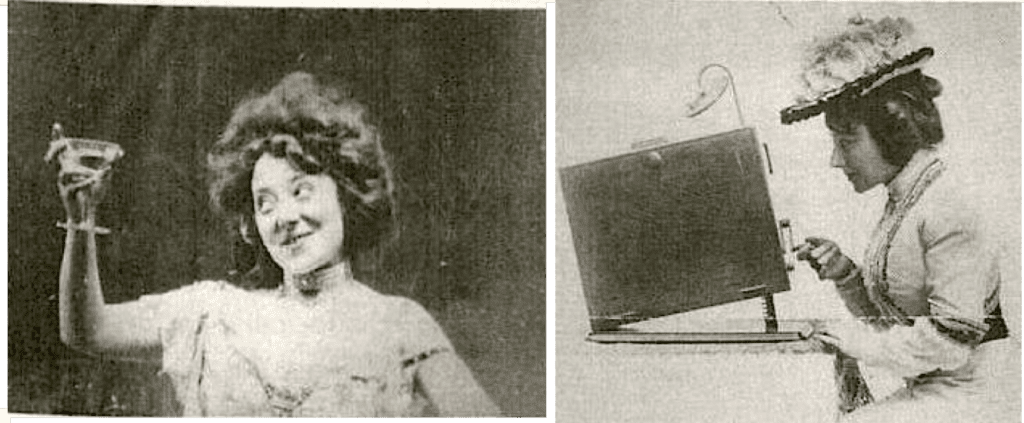

Held was not only using the film to promote her stage celebrity, she was appearing in advertisements for the Mutoscope machine. Perhaps to counter the peep-show’s reputation as stag entertainment, the ads showed Held as a viewer of Mutoscope fare.

New York Clipper, September 26, 1903 (center). The LOC Prints & Photographs Online Catalog (PPOC) record reads: “Anna Held and a mutoscope.” Photograph (left) by the American Mutoscope & Biograph Co., 1901. Reproduction number: LC-USZ62-7321 (b&w film copy neg.). The colorized image comes from a stock photo vendor.

New York Clipper, September 26, 1903 (center). The LOC Prints & Photographs Online Catalog (PPOC) record reads: “Anna Held and a mutoscope.” Photograph (left) by the American Mutoscope & Biograph Co., 1901. Reproduction number: LC-USZ62-7321 (b&w film copy neg.). The colorized image comes from a stock photo vendor.

In the previous post, we saw that the genres and categories of early cinema were changeable and sometimes confused or uncertain about naming conventions. That same 1902 catalog listed films under 16 headings: Comedy, Vaudeville, Trick, Sports and Pastimes, Notable Personages, Railroads, Scenic, Fire and Police, Military, Parades, Marine, Children, Educational, Expositions, Machinery, and Miscellaneous.

Look at how they illustrated the Vaudeville section!

Even the term vaudeville doesn’t quite cover the territory. Both Anna Held and early motion pictures appeared not only in vaudeville theaters, but also in other stage venues (variety, burlesque, Broadway, opera houses, and the wonderful panoply of theatrical enterprises that existed when movie theaters joined the mix).

Film historian Jennifer Peterson offers this insight in her 2013 book Education in the School of Dreams: Travelogues and Early Nonfiction Film. After noting the 16 AM&B classifications, she (via Tom Gunning) points out that another Biograph catalog of 1902 offered this schema: “comedy views; sports and pastimes views; military views; railroad views; scenic views; views of notable persons; miscellaneous views; trick pictures; marine views; children’s pictures; fire and patrol views; Pan American Exposition Views; vaudeville views; educational views; parade pictures:” She concludes (p. 290) “the slight variation between categories (the different order, the addition of the word ‘views’ to many of the categories in one list) even in these two lists from the same company in the same year indicates the high level of slippage possible in early film classifications.”

Trade periodicals for the film industry did not appear until 1907, making motion picture sales and rental catalogs indispensable primary sources for historical research. Again we owe Charles Musser a debt of gratitude for making a large number of these publications more accessible. He worked with archives that photographed such documents for a microfilm publication, which he edited. A Guide to Motion Picture Catalogs by American Producers and Distributors, 1894–1908 (University Publications of America, 1985). Taking the microfilm into the digital realm, Rutgers University offers downloadable PDFs of 508 documents. The AM&B Picture Catalogue series is particularly valuable, often showing strips of film for works that are otherwise lost.

The images of Osterman (below) are low-resolution, reflecting what’s currently available on-line. However, one can consult the originals at the Museum of Modern Art’s Film Study Center. And, again as part of the ongoing Media Ecology Project as well as the Media History Digital Library, Paul Spehr tells us that discussions are underway to have new high-resolution scans made of the original paper booklets. He adds (in an e-mail today) that a second copy of Biograph Picture Catalogue exists at the Seaver Center, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History. “It’s in the Van Guysling Collection of American Biograph Co. George E. Van Guysling was head of the West Coast Office of AM&B, and briefly, 1905-1907 or 8, manager in NYC. His brother was also at the LA office.” MoMA’s copy has productions No. 1 through 3007 (April 1905) + Nos. 3171-74, scenes after the San Francisco earthquake in 1906. “In many cases, he says, “it is almost impossible to read the title information at the bottom.”

How does the information found there relate to Spehr’s spreadsheet of AM&B productions that MEP and NYU Film Historiography students are working with?

Paul says the “title in Column A is the title in the production log book, which is a working title, probably as entered at the time the film was processed. The titles in Columns O, P, & Q. are from the AFI Catalog, Film Beginnings, 1893-1910. Eli Savada who compiled it was very good at searching out all variations. Column O would be the title as it appears there or in Howard Walls’s Motion Pictures 1894-1912 or Niver’s PP Catalog.” This explains, for example, why the footage seen above was logged during production as two pieces (Bust View and Full Length) but given one title, Anna Held, when the two films were jointly deposited for copyright. To confuse matters more, the Biographers only registered some motion pictures for copyright months or years after they had been shot. Beginning in 1901, U.S. Copyright Office registrations for photographs — and therefore paper prints of motion pictures — were assigned numbers preceded by the letter H.

Niver’s entry is: Anna Held. ©H16386 Apr. 12, 1902. Date [of production]: May 24, 1901.

However, Walls adds a second H number and a third date: Anna Held. © 29 May 1901; H4670. © 12 April 1902; H16386. At first it is not clear why Niver omitted the first copyright (of May 29, 1901). But then few things were clear about motion picture copyright in 1901. As we’ve learned, U.S. law did not allow movies to be copyrighted as movies until 1912. (See Wendi A. Maloney’s “Centennial of Cinema Under Copyright Law,” on the LOC blog.) Niver was correct, which I discovered thanks to a lone footnote in an appendix in Patrick G. Loughney’s invaluable dissertation, “A Descriptive Analysis of the Library of Congress Paper Print Collection” (1988). He lists film companies (“claimants”) and the number of works each produced, by year and genre. One “unidentified” item from Biograph has an asterisk, noting “Anna Held (29 May 1902, H4670) is an endorsement/publicity photograph (8″ x 10″) showing the singer posing with a tabletop model of a Mutoscope” (p.333).

Minor mystery solved. The photograph is one of four of Held in David Robinson’s 1995 book From Peep Show to Palace: The Birth of American Film.

But, wait! Our bible — Howard Lamarr Walls, Motion Pictures, 1894-1912: — lists yet ANOTHER film: Anna Held, no. 10. © American Mutoscope & Biograph Co.; 11 July 1901; H5921. Is this a lost film? Probably not. Loughney indicates this registration “has been identified as an 8 x10 publicity still and does not represent a motion picture registration” (p. 368, note 3).

What does the photo show? Its title and copyright number are not in the LOC catalog. Presumably it is not the image of Held with a tabletop mutoscope. However, Alexis Ainsworth’s working database of Paper Print fragments lists the title Anna Held commercial. It matches the Walls copyright entry, H5921, July 11, 1901, Anna Held, no. 10. But the notes say the PPC has 4 x 6 inch prints. More than one. Copyright deposits for motion pictures, even many years after 1912, often included only a few still images. Sometimes these were printed frame enlargements, other times short strips of consecutive frames. Could Anna Held commercial in fact have been a motion picture, with some of the frames deposited as H5921? It’s not in the AM&B production log. But the Fragments database has a note: the numeral appearing in the “corner may indicate internal production number, i.d.” Researcher Buckey Grimm is currently examining the Paper Prints fragments and will look into this conflicting evidence.

Returning to the evidence found in the Biograph Photo Catalogs (as they are listed in the Rutgers University holdings), here are samples of Kathryn Osterman’s filmography.

Her lone pre-1903 film The Art of Making-up (1900) is laid out on a page with a burlesque sketch and two actualities.

The 1902 Picture Catalogue‘s synopsis misspells both of her names! (None of the 1903 films or catalogs identify her by name.) The Art of “Making-Up” is described this way.

The 1902 Picture Catalogue‘s synopsis misspells both of her names! (None of the 1903 films or catalogs identify her by name.) The Art of “Making-Up” is described this way.

Katherine Ostermann, the well-known vaudeville comedienne, in a complete exposition of the methods of “making-up” the face for the stage. She shows the penciling of the eye-brows, blackening the eye lashes, rouging the lips, applying the grease paint and so forth. The work is done in a very dainty and interesting way. Only the head and shoulders of the subject are shown; the figure thus being very large.

Osterman’s Boudoir pose appears alongside a banal actuality of 1903.

Four more of her 1903 films are illustrated together.

.

.

And The Rose is revealed to be composed in the same manner as Lucky Kitten.

The 18-shot A Search for Evidence is reduced to three frames, each a different keyhole shot, each of which is a woman’s point-of-view shot.

Certainly higher-resolution copies of these rare images will be most welcome, and may reveal details allowing better analyses. Particularly for those early AM&B films shot on the 68mm format better copying will give us a better perception of how stunning the original images were. “Old movies” are too often ignored simply because we can’t take the same kind of pleasure in watching inferior copies. When contemporary audiences are shown some of the restored large-format Biograph films, they still elicit thrills and give aesthetic pleasure.

§ An avant-garde aside:

→ Returning to where we started this Film Historiography course — latter-day avant-garde uses of early cinema and its “attractions” — we find evidence of that pleasure. After seeing 35mm AM&B prints restored by the Netherlands Filmmuseum and BFI at the 2004 Orphan Film Symposium, filmmaker Bill Morrison was inspired to make his ultra-widescreen Outerborough (2005, 9 minutes). He used a high-resolution copy of Across Brooklyn Bridge (American Mutoscope Co., 1899), which shows a rail ride crossing the East River. Outerborough is a structuralist diptych, with the original footage run forward then backward, alongside its mirrored image. Watch it on Morrison’s Vimeo site.

Commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art. Music by Todd Reynolds. Postproduction by Cineric.

Also known as New York to Brooklyn Taken from Car Running across Brooklyn Bridge, the 1899 movie is not in the Paper Print Collection. An assembly of three 90-foot rolls of 68mm film, Across Brooklyn Bridge was virtually unseen until 2004, when the BFI copied it to 35mm. The original sales catalog read: “This picture is very novel and interesting. It gives the complete trip from the station at the New York City end of the bridge to the station at the Brooklyn end, as seen from the front end of a third rail car running at high speed. The entire trip consumes three minutes of time, during which abundant opportunity is given to observe all the structural wonders of the bridge, and far distant river panorama below.” Bill Morrison writes: “For modern audiences it is similarly rarefied view we can no longer experience. . . . no train crosses the bridge anymore, and no vehicle can travel over on its median as that trolley did. The unique central perspective lends itself to abstraction and time travel: the journey from one side of the East River to the other becoming a unit of both time and space, increasingly compressible and distributable.”

Kinesthetic films, Gunning called them in a companion piece to his attractions essay. He notes that a very early American Mutoscope actuality, The Haverstraw Tunnel (1897), caused a sensation. A New York newspaper described the screening of the Haverstraw recording in sensuous language, words that hint at the aspects of early cinema that resonated with experimental filmmakers decades later: “The way in which the unseen energy swallows up space and flings itself into the distances is as mysterious and impressive almost as an allegory. . . . One holds his breath instinctively as he is swept along in the rush of the phantom cars. His attention is held almost with the vise of a fate.” These words from the New York Mail and Express, rediscovered (in Biograph Bulletins, 1971) in Robert C. Allen’s 1977 dissertation about vaudeville and film, were striking indeed, quoted by many scholars since.

Yet it is not only the “phantom” ride qualities of Across Brooklyn Bridge that made it apt for a structuralist film. The hypnotic repetitions and geometric patterns also captivate the modern eye. Watching Outerborough calls to mind another exceptional American Mutoscope and Biograph production, Interior New York Subway, 14th Street to 42nd Street (1905), showing the new Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT) system that began operations in October 1904.

The MoMA copy is reproduced here, from the National Film Preservation Foundation.

The Library of Congress copy is reproduced here. The metadata do not list a 16mm version, but a 35mm viewing print and dupe negative made at the Library in 1991, from a 35mm negative made by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, ca. 1989. Presumably the digital file derives from the 35mm. But did UCLA make its 35mm copy from the LOC paper copy of 1905? And were the preservationists comparing the LOC and MoMA items?

Preserved by MoMA from the 35mm original camera negative, G. W. Bitzer’s five-minute film remains an absorbing viewing experience in its own right. Yet is also continues to attract media artists wanting to reuse it. Ken Jacobs is perhaps the avant-garde artist most closely associated with the merging early cinema and experimental film. He made his landmark Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son (1969) using Bitzer’s 1905 Biograph film of the same title. Jacobs rephotographed a 16mm copy he purchased from the Library of Congress when Niver’s Paper Print films were newly available. However, Loughney points out that the AM&B copyright deposit that Niver preserved intermixed the movie’s narrative with outtakes. Ten years after Jacobs first deconstructed Bitzer’s film, the Library of Congress acquired an original release print. Biograph sold two different versions (850 and 506 feet). In either case what viewers saw in 1905 apparently did not look like the paper print reanimated sixty years later.

Listen to Ken Jacobs talk about Tom, Tom when it was new. Millennium Film Workshop”s archive has an audio recording of the 1969 talk at St. John’s University — evidence that the gulf between early cinema and later avant-garde artists was not as wide as Gunning worried. Jacobs was enacting and articulating it more than a decade before “The Cinema of Attractions” was published in 1986. This connection remains strong in the twenty-first century. Only a month ago [February 2017], Ken Jacobs’s 3-D digital production Ulysses in the Subway, co-directed by Paul Kaiser, Marc Downie, and Flo Jacobs, debuted at the Museum of Modern Art. Its soundtrack is a field recording of Jacobs traveling across Manhattan to his home. At several points in the hour-long experimental piece we see portions of Biograph’s Interior New York Subway, 14th Street to 42nd Street — ghosted, superimposed, freeze-framed, and stereographically manipulated. Bitzer’s “structuralist” composition abides.

I note, however, the issue of the aesthetic power of early cinema and the problems of provenance. The end credits to Ulysses in the Subway tell us that the footage from 1905 came from a newly digitized copy of the Jacobs 16mm print. As with Tom, Tom, he long ago obtained a copy of the 16mm material that Niver photographed from the Paper Print Collection. This although MoMA (which is working with Jacobs on archiving his collection) holds the beautiful American Mutoscope and Biograph camera original. Curiously, both the promotional text for Ulysses in the Subway and the filmmakers in discussion after the screening, referred to Bitzer’s masterful Interior film as an Edison production. A minor slippage, even if Edison vs. Biograph was the central conflict in the development of the American film industry.

Jacobs abides.

The only other Web access to images from the AM&B Picture Catalogue is from the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History, to which Paul Spehr alluded. Its website has a small photography exhibition called the “Mutoscope and Biograph series.” It features 18 composite image files described as “Early Mutoscope and Biograph short series featuring offensive racial stereotypes of African-Americans in situations considered ‘comic’ at the time.” It’s a curious choice, offering digital access only to offensive racial images. The quality of the LACNHM JPEGs is marginally better than the Rutgers PDFs made from the microfilm copy of MoMA’s originals, but they remain low resolution.

Yet these are valuable primary sources for studying early cinema. In some cases these three frames are all that survive from a given work — or at least the only things accessible.

When film prints or negatives do survive, frame enlargements can reveal much more, even if these are taken from 16mm copies of 35mm paper prints. But we have also learned that for many titles in the Paper Print Collection, 35mm film copies survive elsewhere, sometimes even as original camera negative (OCNs!).

And these can make beautiful images, viz. Barbara Flückiger’s photograph of MoMA’s Three American Beauties on the Timeline of Historical Film Colors. (The Timeline team received a European Research Council grant of €2.9 million [more than $3,000,000], the largest amount ever awarded to a digital humanities project.)

Here’s a final case to consider.

The Library of Congress has excellent material on the AM&B film From Show Girl to Burlesque Queen (1903), part of the Paper Print Collection. But for some reason the LOC catalog metadata does not mention Niver’s 16mm copying of the paper. (FIAF’s database says there is a 16mm element at LOC; also a mutoscope roll of flip-cards at the George Eastman Museum.) The LOC catalog tell us the Library’s own lab made a 35mm duplicating negative and reference print in 1994. When first putting curated collections of movies on-line in the 1990s, the Library chose early American cinema (since copyrights had expired) and made 35mm copies of the paper prints in order to get the best-looking results to put on the Internet. The new film prints were transferred to Beta SP videotapes. After adding titles and adjusting contrast, the standard-definition video was digitized at Crawford Communications, which compressed the files for Web streaming and download. The MPEG-1 and tiny (160 × 120 pixels) MOV files for From Show Girl to Burlesque Queen were made in 1996. The MP4 file is higher resolution and begins with an Academy countdown leader. This version, with LOC logo and voiceover added to the head and tail, is what streams from LOC.gov, as well as, since 2009, from the Library of Congress YouTube channel.

Have a look at the 64-second movie. Note each second on the countdown leader lasts longer than one second, although the motion within the film appears natural. The LOC team decided well in copying the surviving film at 14 frames per second, a slightly slower speed than most films of the period. There was not a correct, standardized frame rate throughout the silent era. Also, speed at which film was recorded in the camera differed from the speed at which a film print was projected. Only synchronous-sound film got standardized as 24 fps after 1927. Of course viewers who looked at FSGtBQ on a hand-cranked mutoscope machine determined their own speed.

Kemp Niver’s 1967 synopsis is not quite lascivious.

A young is woman standing next to some screens, either behind or in the wings of a stage or a dressing room on stage. She begins to remove her clothing — first the dress, then slip, another slip and another — down to her fourth petticoat. With a very fetching smile, she goes behind a screen. Several other articles of clothing fall to the floor, having been tossed over the screen. In the last scene, the young woman emerges. She is half-clothed but is wearing long stockings. The dressing room door opens and man in a band costume [?] looks approvingly at what he sees.

In 1998, when the Library’s National Digital Library created the online exhibition American Variety Stage: Vaudeville and Popular Entertainment, 1870-1920, a scrupulous scholarly summary appeared with the movie.

Opens on a dressing room set with a mirror, dressing table, and chair center stage and a folded dressing screen on the left. A smiling, dark-haired woman enters through the door on stage right, unbuttoning a full-length polka-dot costume. As she undresses, she frequently looks directly at the camera and smiles. She removes her sash or cummerbund, the top with its trailing sleeves, and her skirt, leaving her clothed only in a sleeveless chemise. Smiling directly at the camera, she mischievously slips a strap of the garment off one shoulder, then ducks behind the screen. After the chemise is thrown over the top of the screen, her arm furtively reaches out from behind the screen and grabs a slight garment from the back of the chair and some items from the dressing table. She then emerges wearing a risqué, decorated costume with cap sleeves and a very short skirt, gathered at the waist. Her legs appear to be bare. The woman brandishes a sword, grabbed from under the discarded dress, and strikes a seductive pose as the viewer glimpses a costumed man entering the room.

“Costumed man” sounds more accurate than “man in a band costume” — which almost sounds like a punch line. And does he, as Niver put it, “look approvingly”? In fact he (if it is a he) is on screen for less than 1 second when the film ends. This frame was the only one I managed to grab in which his face is visible.

Further, in one of the LOC files (0549.mpg), he does not appear at all. The video ends on this frame.

But this is just a glitch. Costumed Man appears in all other video copies.

More difficult to explain is why the LOC Prints & Photographs Division has relatively high-resolution frame enlargements of From Show Girl to Burlesque Queen. These reveal much more of the original image than any of the video copies. Here are the 3 images.

Note how much of the image in these frame enlargements is cropped from the video version. A lot. Both have a 4 x 3 aspect ratio. Were the frames taken from the 35mm paper print, as the metadata seem to indicate? or perhaps from Mutoscope cards?

The LOC catalog record for the still images indicates they were published in the book American Women: A Library of Congress Guide for the Study of Women’s History and Culture in the United States, edited by Sheridan Harvey (Library of Congress, 2001). Likely the images were created specifically for the book and now are online for open use. Chapter 10, in which these illustrations appear, is an excellent guide to how the Moving Image Section of the LOC Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division is organized. Veteran researchers wrote the chapter: Rosemary Hanes (reference librarian in the Motion Picture Reading Room) and Brian Taves (film historian and LOC cataloguer). A condensed version of their text is here. The whole book is downloadable from the Hathi Trust book scanning project.

One last metadatum is revealing.

The PPOC record for the photographs lists them as part of an LOC “collection” called “Miscellaneous Items in High Demand.” This is a searchable database of more than 80,000 images “singled out for description because copy photographs or digital copies were requested for a publication, exhibition, or other special project that increased demand for the pictures.” In other words, it’s a historiographic tool, offering evidence of how a particular photo/film became better known, more widely circulated, and more accessible than others.

Some relevant reading:

Two marvelous social histories: Robert C. Allen, Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture (U of North Carolina Press, 1991) and Timothy J. Gilfoyle, City of Eros: New York City, Prostitution, and the Commercialization of Sex, 1790-1920 (Norton, 1992).

+

• The Anna Held Museum Papers, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Billy Rose Theatre Division.

• Eve Golden, Anna Held and the Birth of Ziegfeld’s Broadway (U of Kentucky Press, 2000).

• Tom Gunning, “An Unseen Energy Swallows Space: The Space in Early Film and Its Relation to American Avant-Garde Film,” in Film Before Griffith, ed. John Fell (U of California Press, 1983): 355-66

• Gordon Hendricks, Beginnings of the Biograph (Beginnings of the American Film, 1964).

• Karen Lund, “Early Cinema in the National Digital Library,” paper presented at the symposium “Orphans of the Storm: Saving ‘Orphan Films’ in the Digital Age,” University of South Carolina, September 23, 1999, www.sc.edu/filmsymposium/archive/ orphans1999/1.2KarenLund.htm.

Ziegfeld Girl: Image and Icon in Culture and Cinema (Duke UP, 1999), ch. 1, “Celebrity and Glamour: Anna Held.”

• David Monod, “The Eyes of Anna Held: Sex and Sight in the Progressive Era,” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, 10, No. 3 (July 2011): 289-327.

• Jennifer Lynn Peterson, Education in the School of Dreams: Travelogues and Early Nonfiction Film (Duke UP, 2013).

• Paul Spehr, The Man Who Made Movies: W.K.L. Dickson (John Libbey, 2008).

• Dan Streible, “Children at the Mutoscope,” Cinémas: revue d’études cinématographiques /Journal of Film Studies [Montreal] 14.1 (2003): 91-116.

Bonus image:

Not totally forgotten. Anna Held on an iPhone cover.