notes and references for

GLOBAL ASIA: a world of mobility

Introduction

On the Spanish belief that Native Americans were Muslims: Alan Mikhail, God’s Shadow: Sultan Selim, His Ottoman Empire, and the Making of the Modern World. New York: Norton 2020.

Ice Age Asian Migrations to the Americas: David Reich, Nick Patterson, and Andrés Ruiz, “Reconstructing Native American population history,” Nature, 488, 370-374, 11 July 2012.

Quarantine: Vesna Zlata Blažina-Tomić, Expelling the plague: the Health Office and the implementation of quarantine in Dubrovnik, 1377-1533. Montreal : McGill-Queen’s University Press 2015. Chapter 5, “Control of Arrivals in Dubrovnik, 1500-1530.”

On political violence and displacement during the Covid pandemic, see 2020, see “Global Conflict and Disorder Patterns: 2020,” a paper presented at the 2020 Munich Security Conference at a side event hosted by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) in partnership with the Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP). It is an updated and expanded version of Global Conflict and Disorder Patterns: 2019.

On border-making, see Willem Van Schendel, The Bengal Borderland: Beyond State and Nation in South Asia. London: Anthem South Asian Studies, 2005. On its power and violence, see Reece Jones. Violent Borders : Refugees and the Right to Move. Vers0, 2016, and Suchitra Vijayan, Midnight’s Borders: A People’s History of Modern India. Melville House, 2021.

On Area Studies and Asian mobility, see “Maps in the Mind and the Mobility of Asia,” Presidential Address for the Association for Asian Studies, Journal of Asian Studies, 62, 3, November, 1057-1078.(Short version, “Nameless Asia and Territorial Angst,”HIMAL, June, 2003.) Also relevant way to frame my approach would be as an escape from methodological nationalism, on which see Andreas Wimmer, and Nina Glic Schiller. “Methodological Nationalism and Beyond: Nation-State Building, Migration and the Social Sciences.” Global Networks, vol. 2, no. 4, 2002, pp. 301–34; and Anna Amelina, Anna, Devrimsel D. Nergiz, Thomas Faist, and Nina Glick Schiller, editors, Beyond Methodological Nationalism: Research Methodologies for Cross-Border Studies. Taylor and Francis, 2012.

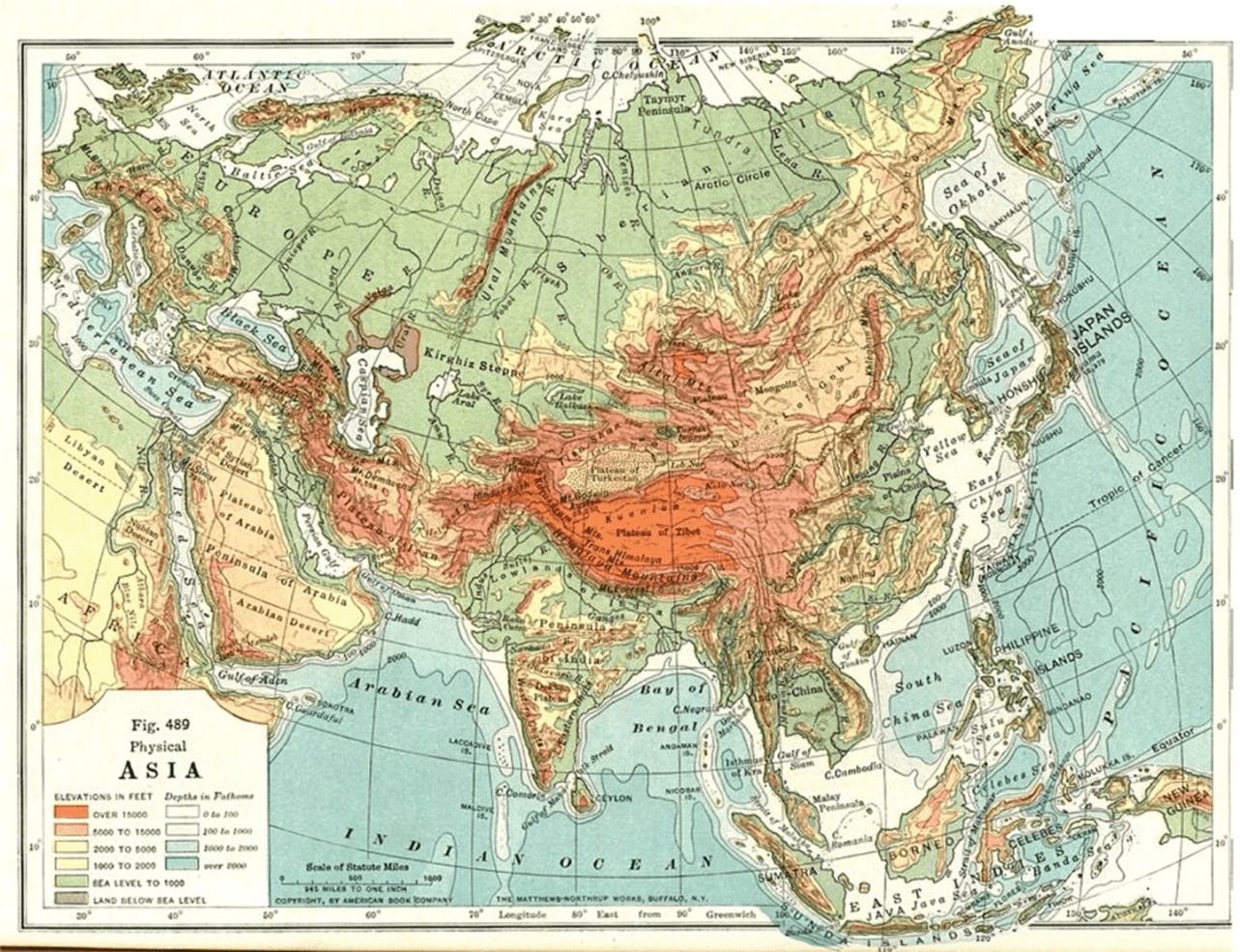

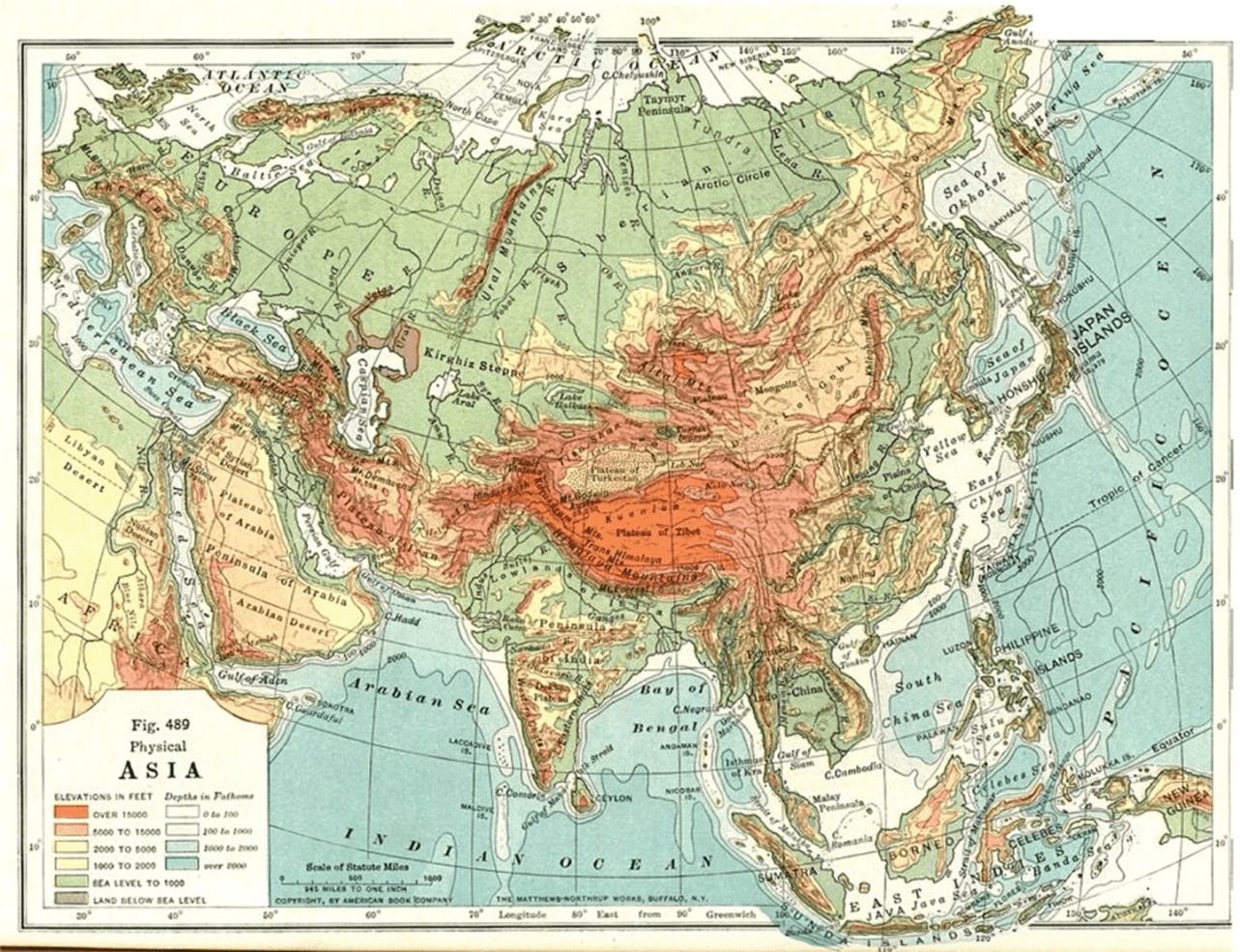

On human activity changing natural environments, these are two early classics: William L. Thomas, editor. Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth. The University of Chicago Press, 1955; and William H. McNeill, Plagues and Peoples. Anchor Random House, 1975 and 1998. For inner Asia, see John Brooke an Henry Misa, “Earth, Water, Air, and Fire: Toward an Ecological History of Premodern Inner Eurasia,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. For South Asia, see Christopher V. Hill, An Environmental History of South Asia. ABC CLIO, 2008. For China: Robert B. Marks, China: An Environmental History. Rowman and Littlefield, 2017.

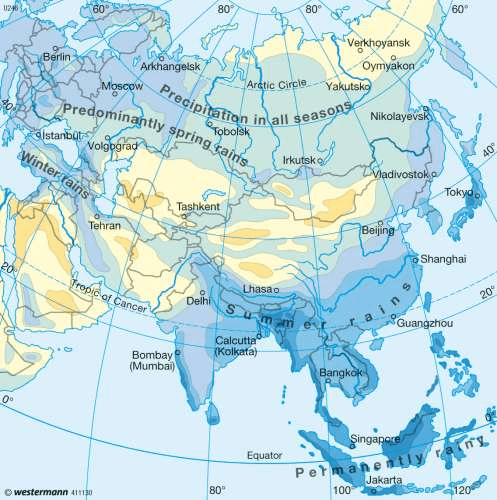

The most detailed application of climate science to to Asian History is Victor B. Lieberman, Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800-1830. Cambridge University Press, 2003 and Strange Parallels, 2 : Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800-1830. Mainland Mirrors Europe, Japan, China, South Asia, and the Islands. Cambridge University Press, 2009, .

On El Nino Famines: Mike Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World. Verso, 2002.

1. Nature

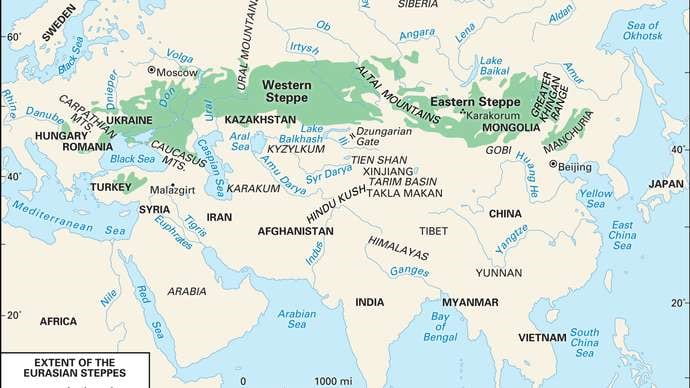

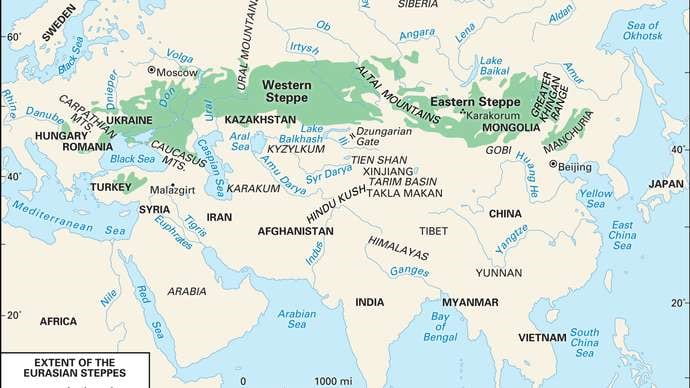

On Furs as currency on the steppe: [1] Peter Frankopan, The Silk Road: A New History of the World. New York: Kopf, 2016. pp. 103-104.

On the ninth century, an Arab traveler and geographer, al Masudi (Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn al-Ḥusayn al-Masʿūdī), see Janet Martin, Treasure of the Land of Darkness the Fur Trade and Its Significance for Medieval Russia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

On North China and the Steppe: Thomas J. Barfield, The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China. London: Basil Blackwell, 1989.

Steppes

On Mineral extraction and eco-damage in Siberia, which benefits distant urban populations and harms locals, see Andrew Wiget and Olga Balalaeva, Khanty, People of the Taiga : Surviving the Twentieth Century, University of Alaska Press, 2011.

On Scythian Gold: Andreeva, P. “Fantastic Beasts of the Eurasian Steppes: Toward a Revisionist Approach to Animal Style Art”. University of Pennsylvania (PhD dissertation), 2018. Stoddert, K. (ed.) From the Lands of the Scythians The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1985. Williams, Dyfri; Ogden, Jack, Greek gold: jewellery of the classical world, Metropolitan Museum of Art/British Museum, 1994.

On North-South Taiga-Steppe trade: Noonan, Thomas S. “The Fur Road and the Silk Road: The Relations between Central Asia and Northern Russia in the Early Middle Ages.” Varia Archaeologica Hungarica, vol. 9, no. 6–7, 2000, pp. 285–301.

On taiga fur trade today: Hong Kong accounts for 70-80% of the world’s total fine fur exports. In a region where the technicalities of producing fur have been around for two to three thousand years, China has become an important manufacturing base for Hong Kong furriers due to their extensive knowledge in the trade. From 2013 to 2014, China produced 40% of the 87.2 million mink pelts produced around the world, amounting to a total global value of US$3.37 billion for that type of fine fur alone …. China …remains one of the biggest manufacturers of fox pelt, manufacturing over 91% of the 7.8 million fox furs produced globally. Forbes online (30 April 2015)

On imperial Russia irrigation on the steppe: Matley, Ian M. “The Golodnaya Steppe: A Russian Irrigation Venture in Central Asia.” Geographical Review, vol. 60, no. 3, 1970, pp. 328–46, https://www.jstor.org/stable/214037.

2. Persia

Naming Iran: Firoozeh Kashani-Sabet,

Frontier Fictions: Shaping the Iranian Nation, 1804-1946. Princeton University Press, 1999, pp.216-226.

Persia and the Persianate world: Marshall G. S. Hodgson,

The Venture of Islam. University of Chicago Press, 1975. Brian Spooner and William Hanaway, editors.

Literacy in the Persianate World : Writing and the Social Order, University Museum Publications, 2012. Abbas Amanat and Assef Ashraf, editors.

The Persianate World : Rethinking a Shared Sphere. Brill, 2018. Nile Green,

The Persianate World. University of California Press, 2019. Mana Kia,

Persianate Selves : Memories of Place and Origin Before Nationalism, Stanford University Press, 2020

.Richard M. Eaton,

India in the Persianate Age, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2021.

On the myth of continents, see Lewis, Martin W. and Karen Wigen. Myth of Continents : A Critique of Metageography. University of California Press, 1997

On Epidemic Histories: Aberth, John. Aberth, John. Plagues in World History. Rowman and Littlefield, 2011. McNeill, William H. Plagues and Peoples. Anchor Random House, 1998. Pandemic Studies Resource Page.

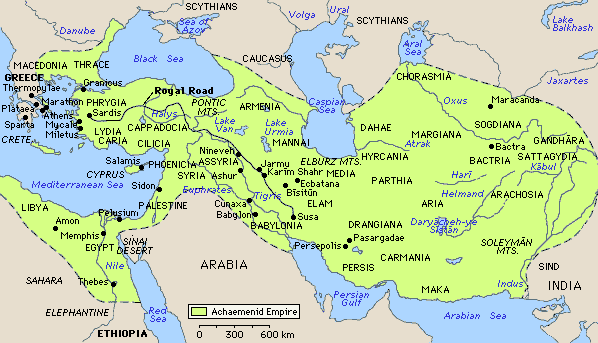

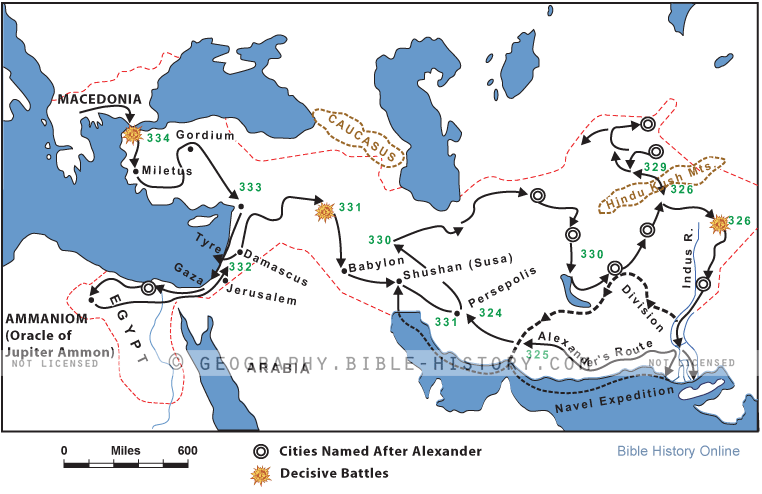

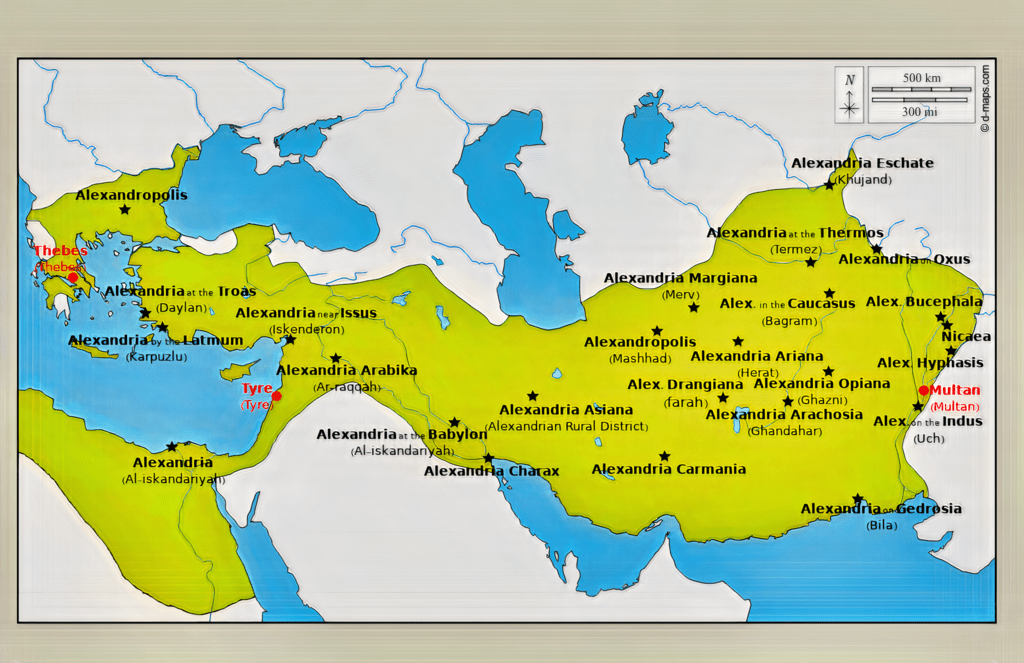

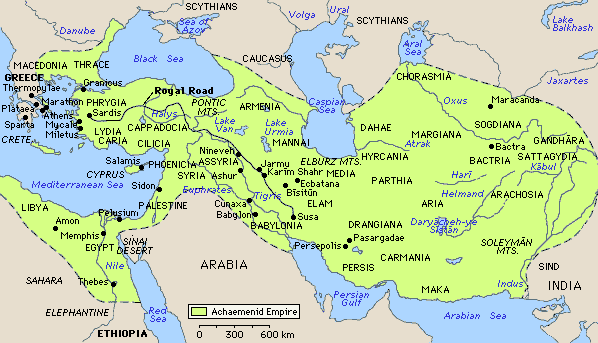

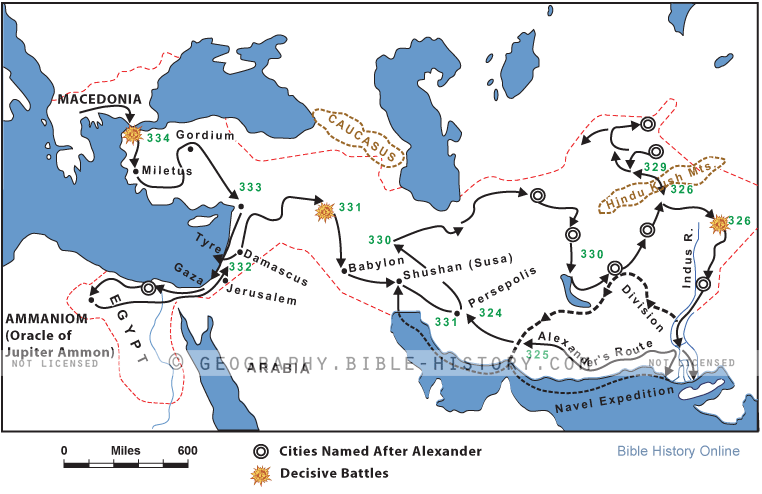

On Alexander’s travels, see: Frank L. Holt, Alexander the Great and Bactria. E.J. Brill, 1988. Ian Worthington, Alexander the Great: Man and God. Taylor & Francis Group, 2004. Andrew Chugg, Concerning Alexander the Great: A Reconstruction of Cleitarchus. 2015. Waldemar Heckel, The Conquests of Alexander the Great. Cambridge University Press, 2007. ” Alexander the Great in Persia.” http://www.the-persians.co.uk/alexander1.htm and Seleucids: https://iranicaonline.org/articles/seleucid-empire. Focus on

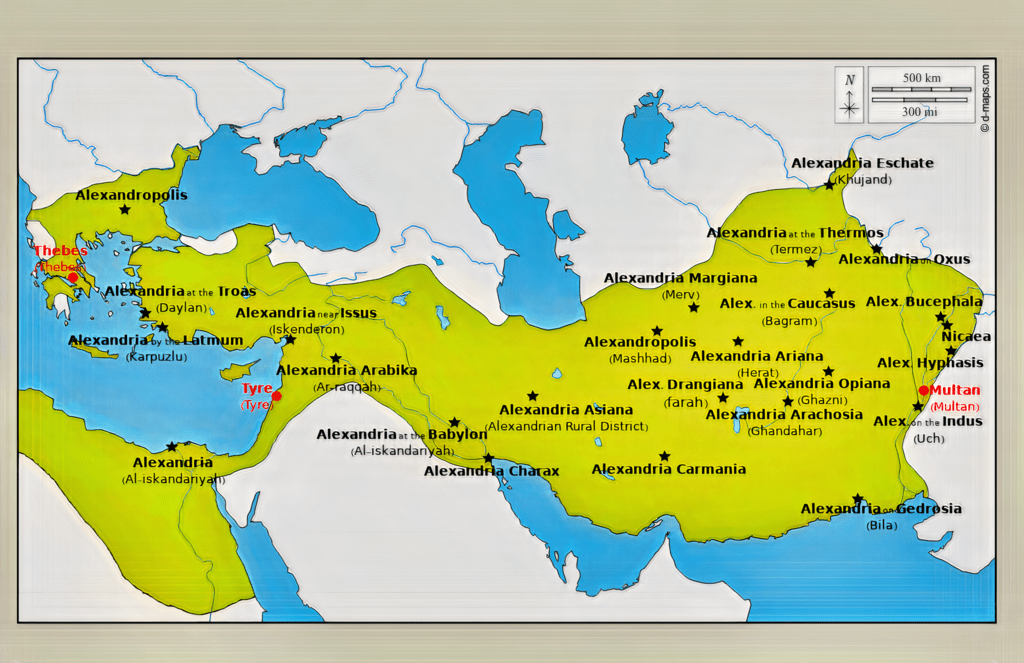

On Samarkand as the center of the world: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samarkand. Samarkand (Maracanda) was the capital of the Achaemenid Sogdian Satrapy and center of Sogdian trade network: Y. Yoshida, “The Sogdian Merchant Network,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. Retrieved 25 Jul. 2021, from . FOR Brilliant online map-indexed articles and AI KHANOUM see: https://www.livius.org/articles/place/ai-khanum/Alexander the Great’s Imperial Route Map (from Bible History Online, 4 Aug 2021

On taiga vulnerability in climate change: “Global Warming Cited as Wildfires Increase in Fragile Boreal Forest, New York Times, 10 May 2016.

On the history and fate of Alexandrias: The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Richard Stillwell, William L. MacDonald, Marian Holland McAllister, Stillwell, Richard, MacDonald, William L., McAlister, Marian Holland, Ed.

On Lake Baikal and the Mongols: https://sacredland.org/lake-baikal-russia/.

On Parthian-Sassanian transition. The Mithra Temple Under the Streets of London (I thank Krishna Kulkarna for this information). Pierfrancesco Callieri, “On the Diffusion of Mithra Images in Sasanian Iran New Evidence from a Seal in the British Museum,” East and West, 40, 1/4 (December 1990), pp. 79-98.http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/sasanian-dynasty, http://www.cais-soas.com/CAIS/Religions/iranian/Zarathushtrian/fire_temple.htm.

On Sasanid-Gupta connections: Hossein Mohammadi, “Indo-Iranian relationship with special reference to Sassanid era (c.336 A.D. – 646 A.D.),” PhD Thesis, University of Pune, August 2007.

William NcNeil, Plagues and Peoples, New York: Anchor Doubleday, 1976, 1998. R.P. Duncan Jones, “The Impact of the Antonine Plague,” Journal of Roman Archaeology, 9, 1996, 108-136. Danielle Gourevitch, “The Galenic Plague: a Breakdown of the Imperial Pathocoenosis and Longue Duree,” History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences, 27, 1, pp.57-69, in M.D.Grmek Memorial Symposium: “The Long Duree in Science and Medicine,” 10 April 2003 (2005), p.59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23333795?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

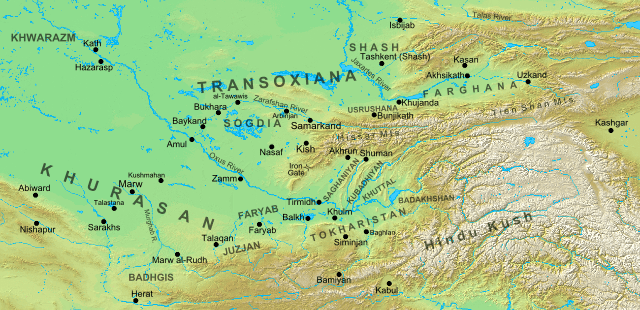

On Sogdiana trade evidence: Valeri Hansen, The Silk Road : A New History. Oxford University Press, 2012, pp. 113-139. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.proxy.library.nyu.edu/lib/nyulibrary-ebooks/detail.action?docID=1015307.

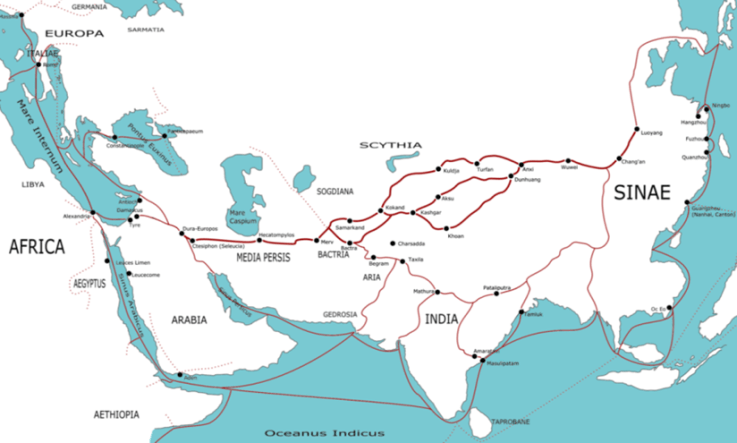

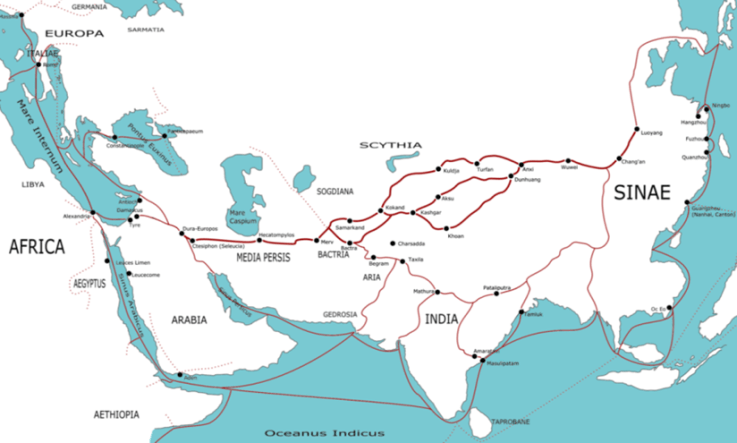

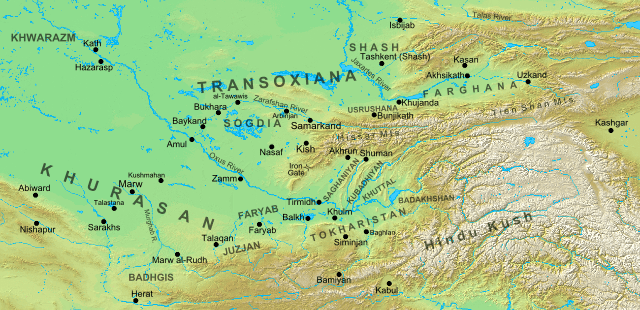

Ptolemy Asia Route Map

Transoxiana Map

On Silk Road: Liu, Xinru and Linda Norene Shaffer. Connections Across Eurasia: Transportation, Communication, and Cultural Exchange on the Silk Roads. McGraw-Hill, 2007. Liu, Xinru. The Silk Roads: A Brief History with Documents. Bedford/St. Martins, 2012. Kuzmina, E. E. The Prehistory of the Silk Road. Edited by Victor H. Mair, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008. Hansen, Valerie. The Silk Road : A New History. Oxford University Press, 2012. Frankopan, Peter. The Silk Road: A New History of the World. Kopf, 2016.

On the Muziris trade agreement: Ships and the Development of Maritime Technology in the Indian Ocean. Edited by David Parkin and Ruth Barnes, Routledge, 2002, pp. 22-7, 36 59n8.

On Greek astrology in India: David Pingree, The Yavanajataka of Sphujidhvaja, 2 Volumes, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1978. See also the Horoscope Astrology Blog.

On empire as political form: Jane Burbank and Frederick Cooper. Empires in World History: Power and the Politics of Difference. Princeton University Press, 2010. Ludden, David. “The Process of Empire: Frontiers and Borderlands.” Tributary Empires in Global History, edited by Peter Filbiger Bang and C.A. Bayly, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, pp. 132–50.

On the imperial China and Nomads: Hansen, Valerie. The Silk Road : A New History. Oxford University Press, 2012. Barfield, Thomas J. The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China. Basil Blackwell, 1989. Perdue, Peter C. China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Asia. Harvard University Press, 2005.

The Nomadic Horse People of Central Asia resource webpage Map of agrarian empires and nomad territories,

circa 100CE

3. India

Bryant, Edwin, and Laurie Patton, editors. The Indo-Aryan Controversy : Evidence and Inference in Indian History, Edited by Edwin Bryant, and Laurie Patton, Taylor & Francis Group, 2005.

David Ludden, An Agrarian History of South Asia, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999

Kenneth R. Hall, A History of Early Southeast Asia Maritime Trade and Societal Development, 100-1500. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2011.

Simon Digby, War-Horse and Elephant in the Delhi Sultanate; A Study of Military Supplies. Oxford: Orient Monographs, 1971.

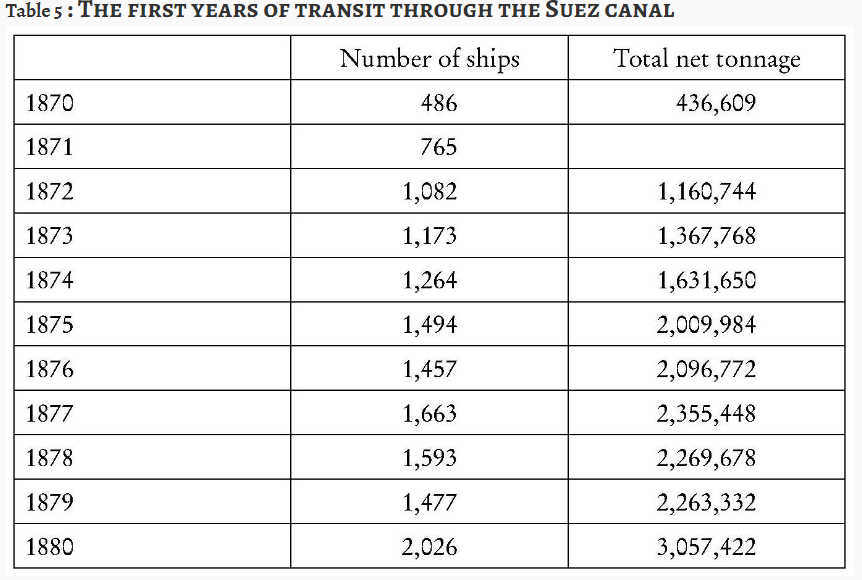

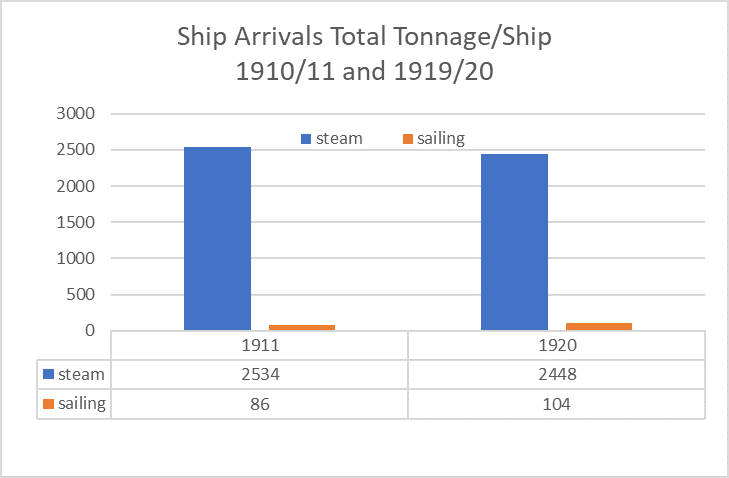

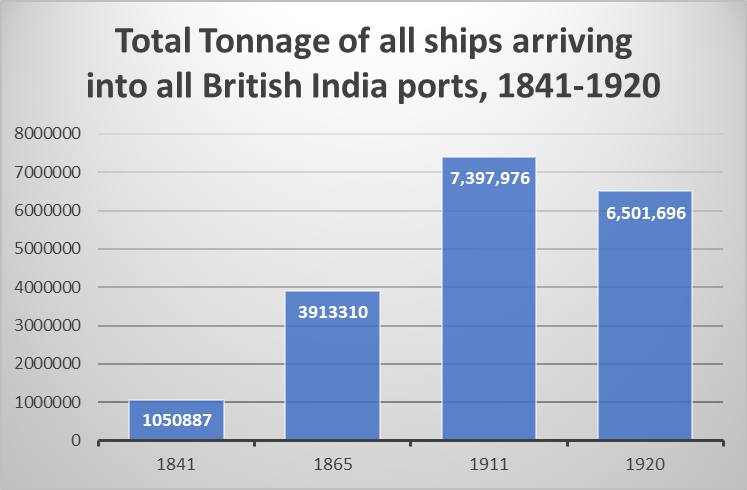

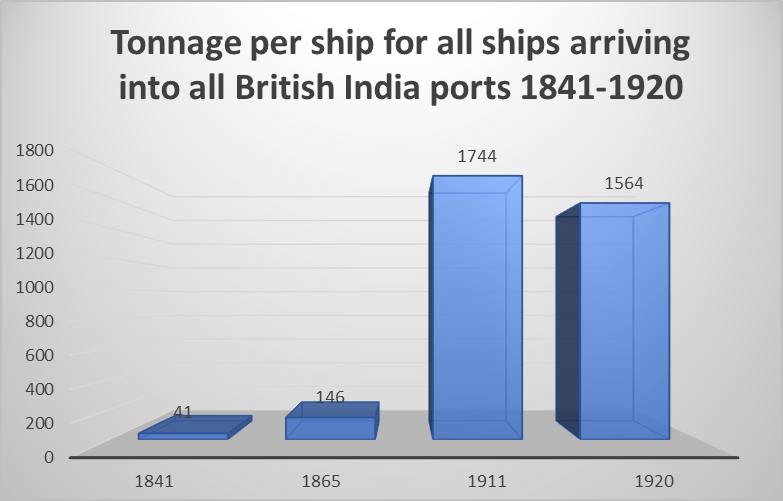

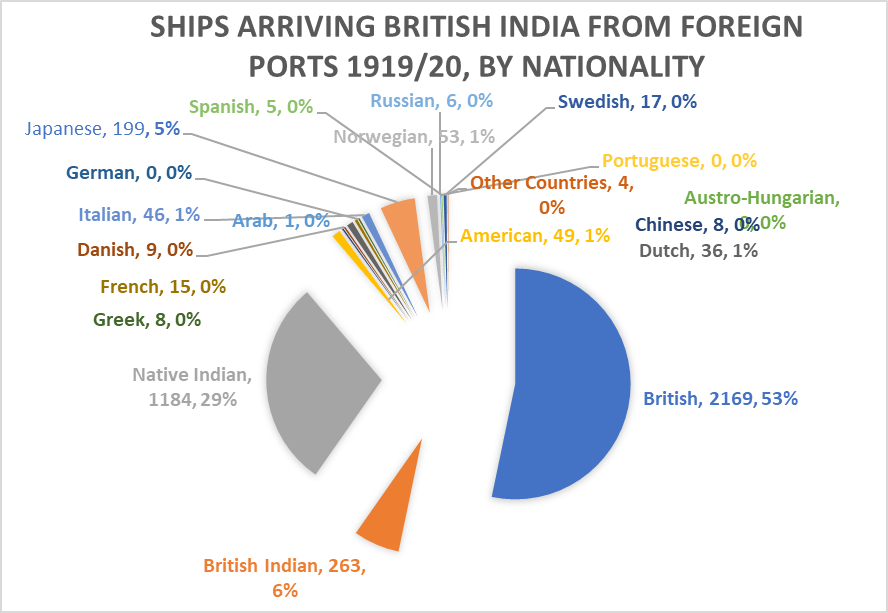

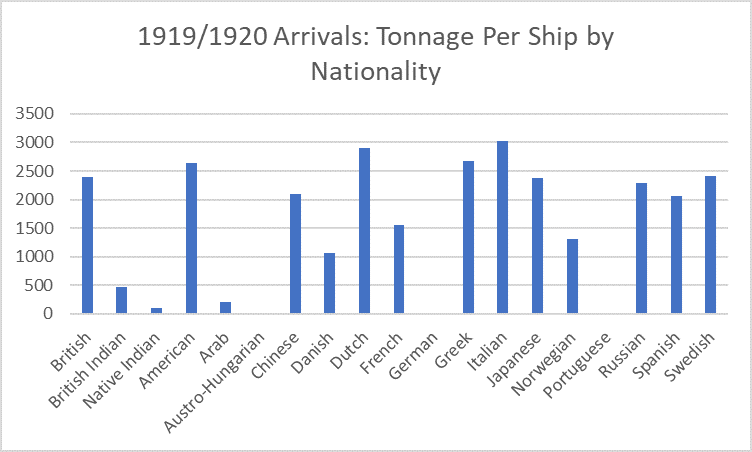

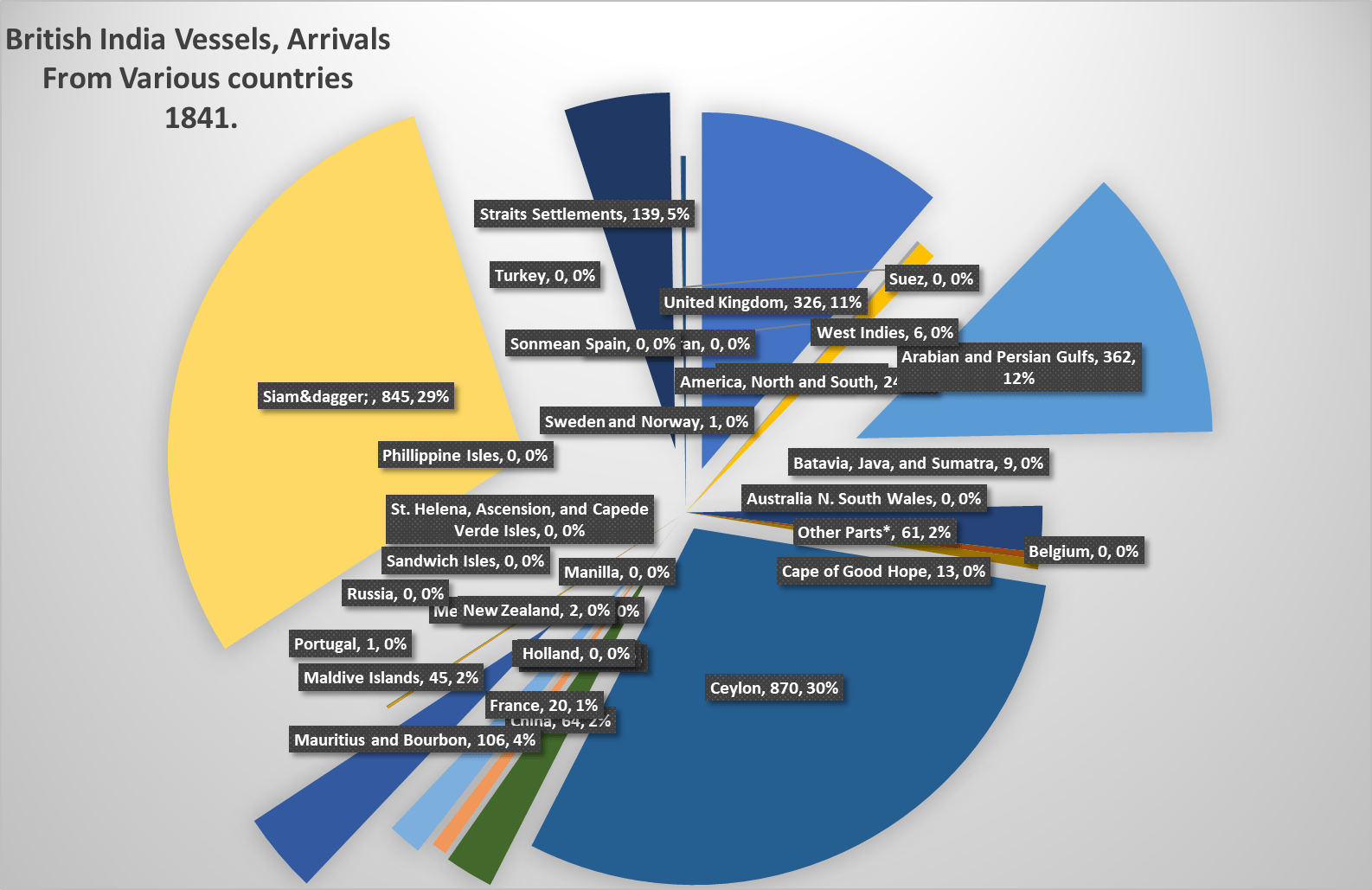

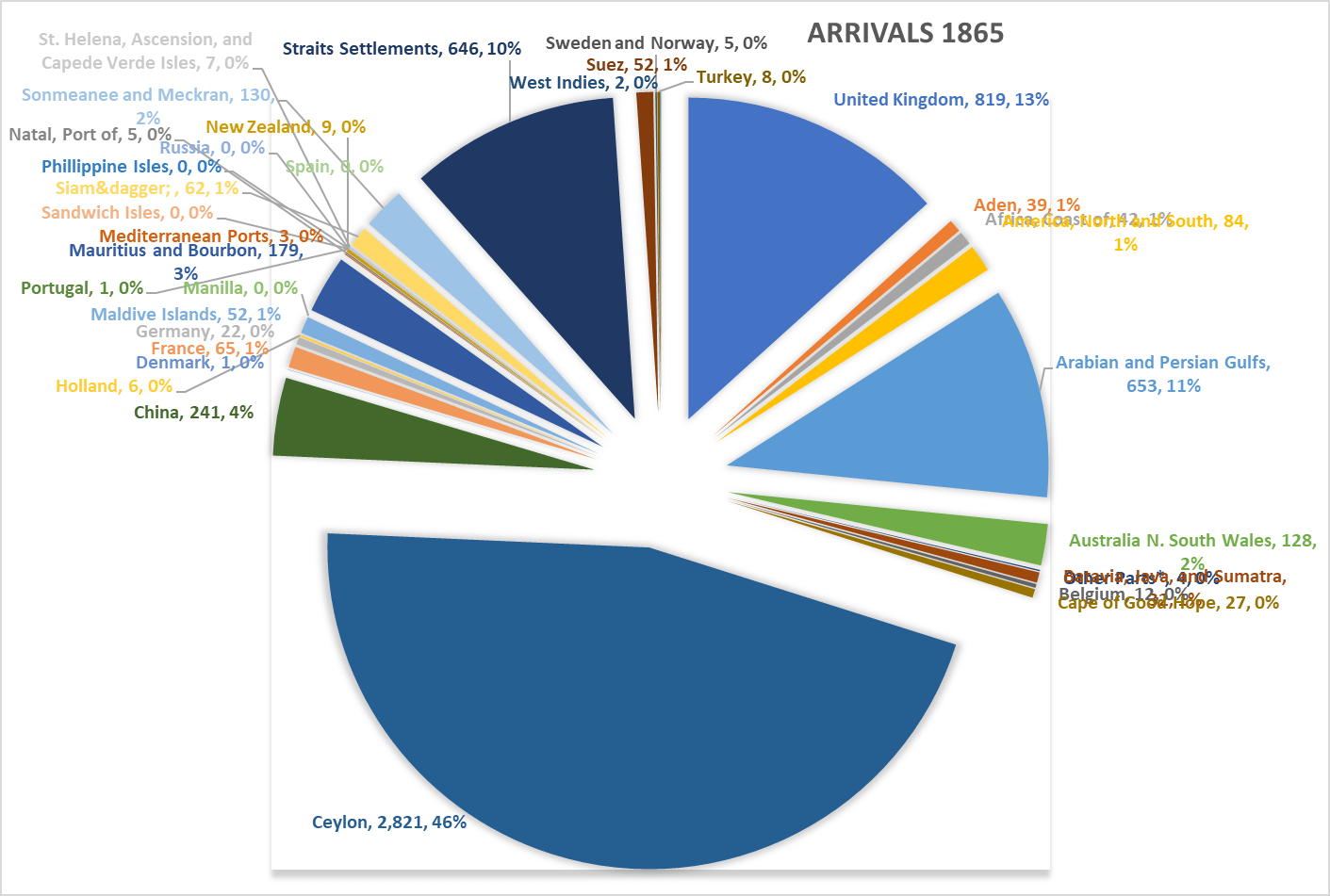

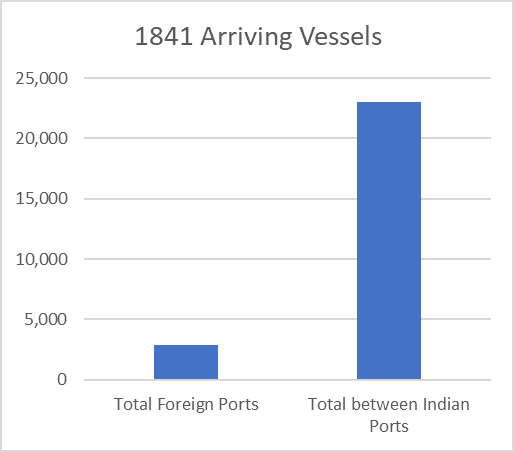

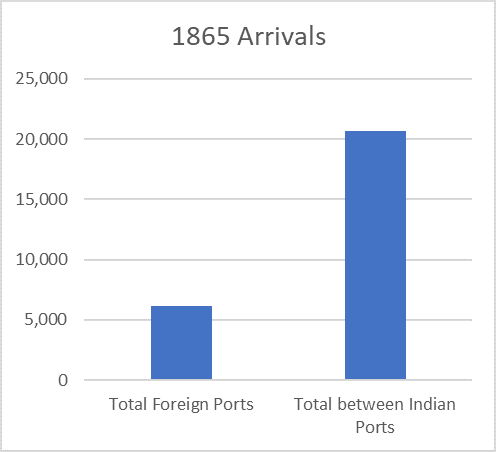

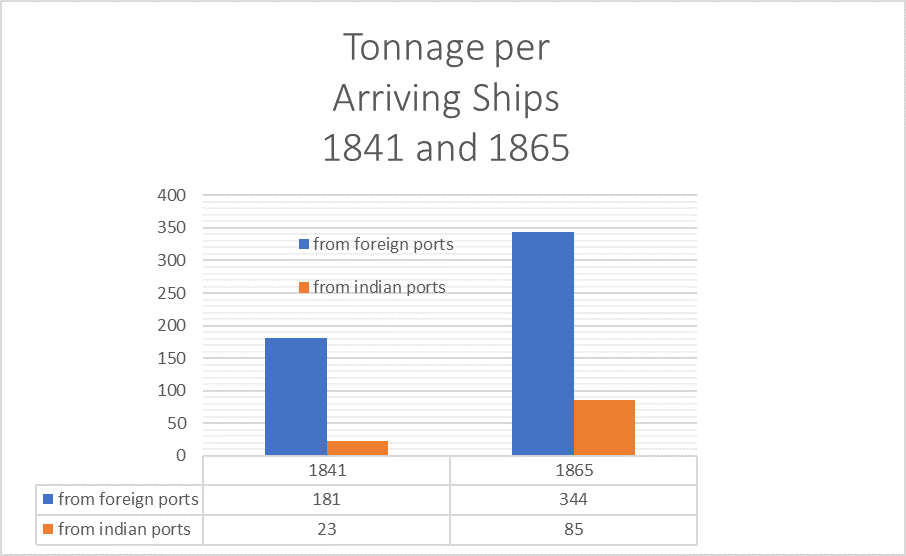

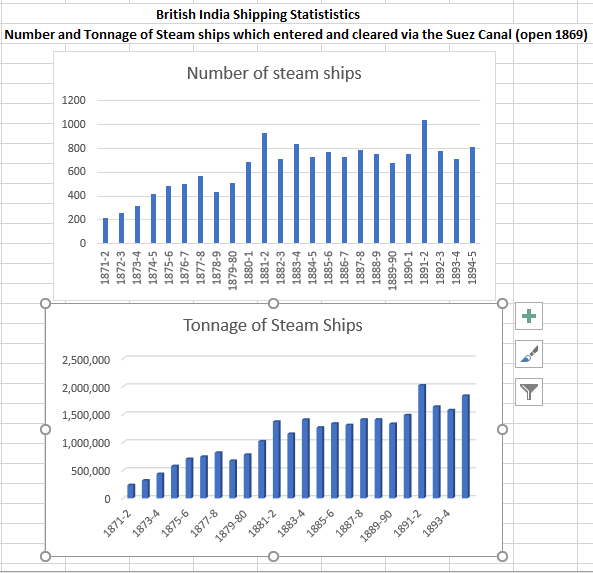

Figures for total ship transit through suez (History of the Suez Canal Company, 1858-2008: Between Controversy and Utility, by Par Hubert Bonin, 2010, Publications d’histoire économique et sociale internationale) indicate that British India trade accounts for a large proportion of initial steam ship transit through the Suez Canal (and its revenues).

Figures for total ship transit through suez (History of the Suez Canal Company, 1858-2008: Between Controversy and Utility, by Par Hubert Bonin, 2010, Publications d’histoire économique et sociale internationale) indicate that British India trade accounts for a large proportion of initial steam ship transit through the Suez Canal (and its revenues).