TEXTS BELOW and in other posts.Dear President Mills and Provost Dopico,I was one of the faculty who was violently arrested last night for trying to protect our students’ right to speech at Gould Plaza. I believe I am owed an apology, as is the entire campus and surrounding community.Not only was the decision to send riot police to break up a peaceful expression of political opinion entirely at odds with what it means to be a university in the public service, the email your office sent out afterwards was disingenuous and unbecoming of university leadership.Neither of you were at the encampment yesterday, so let me share with you what I experienced.The encampment started in the morning and the day was mostly a joyous one. There were children playing and there was singing and chanting at various points. There was no expression of anti-semitism, bigotry, or any hate speech, and a number of Jewish faculty and students who were there can attest to that. There was a Seder. This is very important to establish as a fact. Yes, there were expressions of political opinion critical of Israeli policies, and there were counter-protestors across the street with Israeli flags at various points. But this all falls well within protected speech.If anything, campus security was acting inconsistently and nervously throughout the day, arbitrarily changing the rules at times, such as about who could go in and out, bathroom trips and so on. Campus security actively escalated the tension throughout the day, but it was faculty negotiation that kept the day going smoothly.Things got much worse in the evening. Shortly before 8 pm faculty were called to help protect the students because NYU staff announced they would be calling NYPD. We were expecting that you or someone from the administration would come speak with us before calling the police. I was one of about twenty faculty who arrived at the scene. We came with the express purpose to protect students from arrest and violence, fulfilling our duty to our them and to protect the university’s mission. I brought my faculty ID thinking it would offer me some protection.Riot police in full gear arrived on the scene during evening prayers, seeming to follow the directions of head of NYU security who was off to the side as they stormed in. We the faculty formed a double line of faculty in the mistaken assumption we would be at least heard. Although instructions were being played from a speaker at this point there was no way to disperse and no clear timeline. When it was clear we were about to be assaulted I remembered to take off the lanyard around my neck as a choking hazard, and I am glad I did.I hope the you get to see the body cam footage to see the kind of treatment you visited upon your faculty yesterday. Faculty were handled very roughly, in one instance being shaken and thrown around. Another one was shoved. Next to me was a visibly older faculty member. He was very roughly handled and his hands were tied so tight he complained of not being able to feel his fingers, obviously harmful treatment. I sat next to him and we complained about this for the next two hours until he was processed. When I left the police facility many hours later, he was still there.I was upset and disappointed with the institution and the administration by the time I arrived home at 3:30am but only read your email this morning. It is full of inaccuracies and disingenuous statements and the AAUP has already challenged those claims. But most of all there was absolutely no “hate, disruption, and intimidation” at the student protest. You understand that vague and false allegations like these expose faculty like me, who did not hide my face to doxxing and threats. As a faculty member I feel completely unprotected by the university. I worry in particular about my untenured and insecure colleagues who were there and about what kind of climate we will have at the university moving forward.I have been a faculty here for ten years, and have been teaching for more than twenty, and was a student for a decade before that. I have never been so disappointed and ashamed of my administration as I am now. You are not being called on to agree with the criticisms the students are leveling of Israeli aggression or of the colossal loss of life in Palestine. You are being called on to defend academic freedom and the idea of a university as a place for debate and dissent. This is one of the crucial roles of a university needs to play in a democracy and your actions yesterday have fundamentally undermined our confidence that NYU can play that role. You need to work to earn our trust again.SincerelyGianpaolo Baiocchi

Dr. Linda G. Mills

President, New York University

Dr. Georgina Dopico

Interim Provost, New York University

6 February 2024

Dear President Mills and Provost Dopico,

We the undersigned faculty and staff of New York University write to express our dismay at our university leadership’s repression of pro-Palestine activism and our deep concern over the state of academic freedom. This is of particular concern at this moment because, as the university attempts to silence our calls for ceasefire and our grief for Palestinian lives, academic life and institutions in Gaza are being deliberately decimated by the Israeli military. As noted by the Middle East Studies Association, “Israeli forces destroyed the last remaining major university in Gaza” on January 17 and “hundreds of faculty and staff and thousands of students and their families…have been killed in military assaults.” We join our colleagues in MESA, alongside many other scholars and scholarly organizations, in calling on our university leadership to take the moral stance: please condemn this destruction of university life in Gaza, with all of its consequences for a whole generation of Palestinians.

Not only have you as NYU leaders failed even to mention Gaza in your communications during the nearly four months since the Israeli assault began—in stark contrast to your immediate condemnation of the Hamas attack on October 7—but you have imposed new limits on faculty and students who wish to draw attention to the massive loss of life there. Over the last several months you have sent many letters to the NYU community affirming, in the words of your 10-Point Plan for Student Safety and Wellbeing, “our university’s standing as a place of reflection, free expression, shared respect and security.” But the university’s actions convey a different message: that those of us who take a principled stand against this violent war will be reprimanded, threatened, and disciplined. Last semester, three students brought a lawsuit against NYU that “seeks to require that NYU terminate employees and suspend or expel students responsible for antisemitic abuse.” Although you have acknowledged that the lawsuit is specious and packed with misinformation it seems nonetheless to have inspired NYU leadership to portray anti-war and pro-Palestine speech as inherently discriminatory. In your January 23 letter you exhort faculty and students engaging in protest to avoid “sloganeering that employs phrases meant only to provoke or whose ambiguity is meant to hide hateful intent.” While this exhortation is far from the “plain-spoken” speech you call on us to abide by in the same letter, in the current context it insidiously reproduces the suit’s assumption that pro-Palestinian protest is “hateful,” and its conflation of anti-Zionism with antisemitism. We reject this conflation, and call upon the university to join us firmly and publicly in doing so.

While you have not gone as far as some university presidents to explicitly prohibit specific words and phrases based on their “ambiguity,” you have implied that it is within the power of the university to do so. As we write, the university exercises its power through punitive disciplinary measures toward students and faculty who have criticized Israel’s project of dispossession, occupation, and apartheid in Palestine. The university has summoned students and faculty named in the lawsuit for questioning, subjected some students to disciplinary proceedings for putting up pro Palestine flyers with scotch tape and suspended others for up to a year for removing pro-Israel flyers. The university has also investigated students for writing the names of dead Palestinian

children with chalk on a blackboard, hosting an on-line teach-in featuring Palestinian university students, and for reading Palestinian poetry out loud (without amplification) for 20 minutes in the lobby of Bobst library. Faculty are also increasingly at risk, as illustrated by the recent suspension of adjunct professors Amin Husain and Tomasz Skiba for their extramural critiques of Israel. The university has exerted its power over the right to teach, study, and protest in subtler form as well, from censoring Palestine-related programming (by both faculty and students) at various schools, to frequent reminders of (ever-changing) student conduct policies, to informal warnings to faculty about our syllabi, publications, and political activity. These actions are an unacceptable violation of academic freedom, and a departure from NYU’s practice with regard to every other form of political speech. NYU must protect the space of expression for those on campus who condemn the US-funded Israeli assault on Gaza, its people, and its educational and cultural institutions.

NYU has exacerbated and enforced the culture of fear about campus speech and activism through its intensification of campus security and surveillance, directly in response to the war and subsequent anti-war activity. Through the “10-point-plan” implemented in October, NYU has added “over 9,000 hours of additional, enhanced Campus Safety officer patrol and deployment activity…. We have also strengthened our partnership with the NYPD, and benefited from the addition of more than 1,300 hours of NYPD officer patrol shifts around campus.” We challenge your assertion that armed police represent a “benefit” to the university; rather, the presence of NYPD on our campus disproportionately endangers students of color, and intimidates and threatens all students, faculty, and staff engaging in political protest and speech. In this new climate CSOs swarm peaceful protests and gatherings, employing newly-installed video cameras and ID-swipe data from lobby computers to identify and discipline students and faculty for peaceful protests. Fully-armed police collaborate with the university in response to and anticipation of student protests, stationing themselves adjacent to and inside campus buildings. This represents an abrupt departure from VP of Campus Safety Fountain Walker’s reassurance, in a June 2020 statement to the community, that “As a rule, the presence of the NYPD is not common in NYU’s midst; they have no standing presence here.” We request that the university adhere to its previously agreed-upon memorandum of understanding about the NYPD on campus, roll back the increase of campus safety hours, and refrain from surveillance of the political activities of students and faculty.

NYU is not alone among US institutions struggling to make space for free expression during this perilous time. The repressive environment on our campus reflects a national crackdown on political speech critical of Israel, the occupation, and the current war, manifest in congressional hearings, fired university presidents, and canceled cultural events. To some degree this extraordinary sequence of events reflects what many scholars and legal experts have called “the Palestine exception” to free speech. At the same time, we must recognize the material continuity between the current turn of events and the long-standing attack on Black Studies, critical race studies, and diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives at universities. (The right-wing, book-banning activists behind Claudine Gay’s forced resignation from Harvard are but one example.) We are disappointed to see our university leadership align itself with the same racist and repressive forces that seek to dismantle our shared academic mission, values, and community. We had hoped that NYU, priding itself as it does on its global educational network, would speak out against the demolition of universities and cultural institutions abroad, along with the staggering destruction of infrastructure, ecology, and precious human life. But even if you will not speak out, we will continue to do so.

In the week that NYU gathers to celebrate the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., let us remember one of his most astute and controversial positions: his opposition to the Vietnam War.

Speaking in Riverside Church in April 1967 he connected the dots between racial oppression and poverty at home, and America’s financial and military involvement in a deadly war abroad. Citing a statement from the “Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam,” who had invited him to speak, he affirmed that “a time comes when silence is betrayal” and vowed to break his own silence on Vietnam. He did so in part to maintain his “conviction that social change comes most meaningfully through nonviolent action” a conviction which felt to him increasingly untenable in the midst of a violent war. “I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos,” he wrote, “without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today — my own government.” Our students and colleagues who take action against the war in Gaza today both study and undertake civil disobedience in this tradition, disrupting business-as usual with a dignified demand for peace. As scholars, teachers, and people of conscience, we cannot celebrate Dr. King and remain silent on Palestine. On the contrary, in order to take up his multifaceted call for justice around the world, “we must speak. We must speak with all the humility that is appropriate to our limited vision, but we must speak.”

Sincerely,

- Andrea Adomako, Assistant Professor, English, FAS

- Ashley Ngozi Agbasoga, Assistant Professor, Gallatin

- Khaled Al Hilli, Clinical Faculty, MEIS

- Neveen AlQasas, Research Associate, WRC, NYUAD

- Bedoor AlShebli, Assistant Professor, NYUAD

- Guillermina Altomonte, Assistant Professor, Sociology

- Jens Andermann, Professor, Spanish and Portuguese

- Jane Anderson, Associate Professor Anthropology and Program in Museum Studies 9. Samuel Mark Anderson, Senior Lecturer of Writing, NYUAD

- Prince Steven Annor, Associate Instructor of Engineering, NYU Abu Dhabi 11. Ahmed Ansari, Assistant Professor, NYU Tandon

- Sinan Antoon, Associate Professor, Gallatin

- Emily Apter, Silver Professor of Comparative Literature and French

- John M. Archer, Professor, English

- Mirene Arsanios, Expository Writing Program

- Laure Assaf, Assistant Professor, NYUAD

- Robert Ausch, Adjunct, Psychology, SPS, GSAS and Steinhardt

- Elaine Ayers, Visiting Assistant Professor, Gallatin

- Minju Bae, Assistant Professor, Gallatin

- Gianpaolo Baiocchi, Professor, Gallatin and Sociology

- Abigail Krasner Balbale, Associate Professor Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies and History

- Chris Barker, Associate Director, Institute of Human Development and Social Change 23. Alex Barnard, Assistant Professor, Sociology

- Miriam Basilio Gaztambide, Art History & Museum Studies

- Mohamad Bazzi, Associate Professor and Director, Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies

- Gordon Beeferman, Adjunct Professor, Music

- Elizabeth Benninger, Adjunct Faculty, Gallatin

- Howard Besser, Emeritus Professor of Cinema Studies

- Emanuela Bianchi, Associate Professor, Comparative Literature

- Jamie “Skye” Bianco, Clinical Associate Professor, Media Culture and Communication 31. Federico Bokser Sor, Clinical Assistant Professor, International Relations, Clinical Assistant Professor

- Caroline Bowman, Postdoctoral Lecturer, Philosophy

- Lindsay Brown, Senior Research Scientist, Steinhardt

- Leila Buck, Alumna and Adjunct faculty, Gallatin

- Roxane Caires, Project Managing Director, Steinhardt (IHDSC)

- Dilara Caliskan, Assistant Professor, The Gallatin School

- Marisa Carrasco, Silver Professor of Psychology and Neural Science 38. Michelle Castañeda, Assistant Professor, Performance Studies

- Dean Chahim, Assistant Professor, Department of Environmental Studies 40. Paula Chakravartty, James Weldon Johnson Associate Professor of Media Studies, MCC and Gallatin

- Anastasia Chiu, Scholarly Communications Librarian, Division of Libraries 42. Talya Cooper, Research Curation Librarian, Division of Libraries

- Lou Cornum, Assistant Professor, Social and Cultural Analysis

- Aimee Meredith Cox, Associate Professor of Anthropology, Department of Anthropology 45. Honey Crawford, Assistant Professor, English

- Marie Cruz Soto, Clinical Associate Professor, Gallatin School

- Robyn d’Avignon, Associate Professor, History

- May Al-Dabbagh, Associate Professor, NYUAD

- Kimberly DaCosta, Associate Professor, Gallatin

- Mohammed Daqaq, Professor, Engineering Division, NYUAD

- Ethiraj Dattatreyan, Anthropology

- Matthew Daunt, PhD Candidate, Department of Physics

- Arlene Davila, Professor, Anthropology/SCA

- Subah Dayal, Assistant Professor, Gallatin

- Vanessa Deane, Assistant Clinical Professor of Urban Planning and Public Service, Wagner School of Public Service

- Patrick Deer, Associate Professor, English

- Pierre Depaz, Lecturer of Interactive Media, NYU Berlin

- Dipti Desai, Professor, Art and Art Professions, Steinhardt

- Anne DeWitt, Clinical Associate Professor, Gallatin

- Hasia Diner, Emerita, History and Hebrew and Judaic Studies

- Rossen Djagalov, Associate Professor of Russian and Slavic Studies, FAS 62. Lorraine Doran, Clinical Associate Professor, Expository Writing Program 63. Lisa Duggan, Professor, Department of Social & Cultural Analysis

- Stephen Duncombe, Professor, Galatin School and MCC Steinhardt 65. Zaynab El Bernoussi, Visiting Assistant Professor, Social Research and Public Policy, NYUAD

- Mona El-Ghobashy, Clinical Associate Professor, Liberal Studies

- Hebah Emara, Librarian for Open Innovation, DoL

- Kathy Engel, Associate Arts Professor, Dept of Art & Public Policy, Tisch School 69. Jessica Enriquez, Program Administrator, the LatinX Project

- Gregory Erickson, Clinical Professor, Gallatin

- Jacob Faber, Associate Professor, Wagner School of Public Service and Department of Sociology

- Elisabeth Fay, Clinical Associate Professor, Expository Writing Program

- Liza Featherstone, Adjunct Professor, Journalism

- Sibylle Fischer, Associate Professor, Spanish & Portuguese, History, CLACS 75. Jameson Fitzpatrick, Clinical Associate Professor, Expository Writing Program, College of Arts & Science

- Nicole R. Fleetwood, James Weldon Johnson Professor, Department of Media, Culture, and Communication, NYU Steinhardt

- Juliet Fleming, Professor, Department of English

- Finbarr B. Flood, William R. Kenan, Jr., Professor of the Humanities, Institute of Fine Arts & Dept. of Art History

- Valerie Forman, Associate Professor, Gallatin

- Rosalind Fredericks, Associate Professor, Gallatin

- Hannah Freed-Thall, Associate Professor of French

- Elaine Freedgood, Professor, Dept of English, FAS

- Tania Friedel, Clinical Associate Professor, Expository Writing Program 84. Sharon Friedman, Gallatin

- Ifeona Fulani, Clinical Professor, Liberal Studies

- Andrea Gadberry, Associate Professor, Gallatin and FAS (Dept. of Comparative Literature)

- Toral Gajarawala, Associate Professor, English, CAS

- Ola Galal, Faculty Fellow, Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies 89. Alexander R. Galloway, Professor, MCC

- Tejaswini Ganti, Associate Professor, Anthropology

- Brett Gary, Associate Professor, MCC

- Benjamin Gassman, Clinical Associate Professor, Expository Writing Program 93. Charles Gelman, Adjunct Professor, Gallatin

- Michael Gilsenan, Emeritus, Meis and Anthropology

- Meira Gold, Faculty Fellow, Gallatin

- Martín Gómez, ‘10 CAS Alum & IT Manager, NYU Stern

- Sophie Gonick, Associate Professor, Social & Cultural Analysis

- Jeff Goodwin, Professor, Sociology

- Gayatri Gopinath, Professor, Dept of Social and Cultural Analysis

- Hannah Gurman, Clinical Associate Professor, Gallatin

- Steven Hahn, Professor of History

- Hala Halim, Associate Professor, Departments of Comparative Literature and Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies

- B. Colby Hamilton, Chief Communications Officer, McSilver Institute for Poverty Policy and Research

- Yukiko Hanawa, Clinical Associate Professor, East Asian Studies

- Lynne Haney, Professor, Sociology

- Lennie Hanson, Asst. Professor, English

- Ellie Happel, Adjunct Professor, School of Law

- April M. Hathcock, Director of Scholarly Communications & Information Policy, Division of Libraries

- Pato Hebert, Associate Arts Professor, Department of Art & Public Policy 110. Radha Hegde, Professor, MCC

- Phyllis Heitjan, Reference Associate, Division of Libraries

- Caroline Hiott, Research Scientist, Institute of Human Development and Social Change, Steinhardt

- David W Hogg, Professor of Physics and Data Science

- Karen Hornick, Clinical Associate Professor, Gallatin

- Kristin Horton, Associate Professor of Practice, Gallatin

- Amin Husain, adjunct faculty, Steinhardt and Social and Cultural Analysis 117. Hafeezah Hussein, Instruction Assessment Associate, Libraries

- Asli Igsiz Associate Professor MEIS

- Yeshim Iqbal, Senior Research Scientist, Steinhardt

- Misho Ishikawa, Assistant Professor, English

- Natasha Iskander, Professor, Wagner School of Public Service

- Amal Ismail, Research Fellow, Marine Biology Lab, NYU Abu Dhabi 123. Asmaa Jrad, Postdoctoral Associate, NYUAD WRC

- Harini Kannan, UX Analyst, Division of Libraries

- Marion Kaplan, Professor Emerita of Modern Jewish History

- Rebecca E Karl, Professor, History Department

- Nina Katchadourian, Clinical Professor, NYU

- Marion Katz, Professor of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies

- Rosanne Kennedy, Assistant Clinical Professor, Gallatin

- Arang Keshavarzian, Associate Professor, Department of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, FAS

- Erich J Kessel Jr, Assistant Professor of Black Diaspora Arts, IFA 132. Dipti Khera, Associate Professor, Art History and Institute of Fine Arts 133. Roozbeh Kiani, Associate Professor, Center for Neural Science

- John King, Associate Adjunct Professor, SPS/DAUS, member Joint Council ACT-UAW local 7902

- Eugenia Kisin, Associate Professor, Gallatin

- Ilya Kliger, Associate Professor, Russian and Slavic

- Chenjerai Kumanyika, Assistant Professor, Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute, CAS 138. Michael S Landy, Professor of Psychology and Neural Science

- Toby Lee, Associate Professor, Cinema Studies

- Karen Lepri, Associate Clinical Professor, Expository Writing Program 141. R. L’Heureux Lewis-McCoy, Associate Professor, Applied Statistics, Social Science and Humanities, Steinhardt

- Tatiana Linkhoeva, Associate Professor, History

- Julie Livingston, Silver Professor of Social and Cultural Analysis

- Zachary Lockman, Professor, MEIS and History

- Ying Lu, Associate Professor, Steinhardt

- David Ludden, Professor, Department of History

- Ritty Lukose, Associate Professor, Gallatin

- Beth Boyle Machlan, Clinical Associate Professor, Expository Writing Program 149. Samer Madanat, Professor, NYUAD

- Chase Madar, Adjunct Professor, NYU Gallatin

- Rachel Mahre, Audiovisual Processing Archivist, Division of Libraries 152. Jane B Malmo, Teacher (retired) Dept of Drama TSOA

- Amita Manghnani, Associate Director, Asian/Pacific/American Institute 154. Michele Matteini, Associate Professor, Art History and Institute of Fine Arts 155. John Maynard, Emeritus Professor, Department of English

- Anna McCarthy, Professor, Cinema Studies, Tisch School of the Arts 157. Maureen N. McLane, Professor, Dept. of English, FAS

- Prita Meier, Art History and Institute of Fine Arts

- Maria Mejia, Open Scholarship Librarian, Division of Libraries

- Eve Meltzer, Associate Professor of Visual Studies, Gallatin

- Danny Mendelson, Division of Libraries

- Sienna Merope-Synge, Adjunct Professor of Law, School of Law 163. Mary Mezzano, Undergraduate Program Administrator, English

- Duja Michael, Data Scientist, Steinhardt (IHDSC)

- Mara Mills, Associate Professor, Department of Media, Culture, and Communication, Steinhardt

- Ali Mirsepassi, Professor, Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, Gallatin/MEIS 167. Nicholas Mirzoeff, Professor, MCC.

- Michele Mitchell, Associate Professor, History

- Mostafa Mobasher, Assistant Professor, NYUAD Engineering

- Jorge Montalvo. Advanced Manufacturing Workshop Manager. Engineering 171. Jennifer L. Morgan, Professor, SCA & History

- Sara Murphy, Clinical Associate Professor, Gallatin

- Bernadette Myers, Faculty Fellow, Gallatin

- Andrew Needham, Associate Professor of History and Director of the Native Studies Forum

- Vasuki Nesiah, Professor of Practice, The Gallatin School

- Danielle Nista, Assistant University Archivist, NYU Special Collections 177. Mary Nolan, Professor of History emerita

- s.o. O’Brien Operations Manager, Division of Libraries

- Gerard O’Donoghue, Clinical Associate Professor, Expository Writing Program, FAS 180. Shannon O’Neill, Curator for Tamiment-Wagner Collections, NYU Special Collections 181. Sana Odeh, Clinical Professor, Computer Science, NYU

- Elayne Oliphant, Associate Professor, Departments of Anthropology and Religious Studies

- Noah Ortega, Adjunct Lecturer, Tisch Drama

- David Palmer, Adjunct Assistant Professor, Liberal Studies, CAS 185. Chrysa Papadaniil, Senior Research Scientist, Center for Brain Imaging 186. Crystal Parikh, Professor, FAS

- Robert Parthesius, Associate Professor Heritage and Museum Studies NYUAD 188. Asli Peker, Clinical Professor, FAS

- Ann Pellegrini, Professor, Performance Studies, TSOA

- Ren Pepitone, Assistant Professor, History

- Roxane Pickens, Community Engagement Librarian & Head, External Engagement, Division of Libraries

- Amira Pierce, Associate Clinical Professor, Expository Writing Program 193. Maurice Pomerantz Professor of Literature and Arab Crossroads NYUAD 194. Jillian Porter, Visiting Associate Professor, Russian and Slavic Studies and Comparative Literature

- Sonya Posmentier, Associate Professor, English

- Myisha Priest, Gallatin

- Sara Pursley, Associate Professor, Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies 198. Mohammad A. Qasaimeh, Associate Professor of Engineering, NYUAD 199. Ramin Rahni, Postdoctoral Associate, Biology

- Arvind Rajagopal, Professor, Media Studies

- Vicky Rampin, Librarian for RDM & Reproducibility, Division of Libraries 202. Mitra Rastegar, Clinical Associate Professor, Liberal Studies

- Michael Rectenwald, Professor, Liberal and Global Liberal Studies (Retired) 204. Dara Regaignon, Associate Professor, English

- Timothy J Reiss, Professor Emeritus, Comparative Literature

- Erica Robles Anderson, Associate Professor of Media, Culture, and Communication, Steinhardt School of Human Development

- Sahar Romani, Clinical Assistant Professor, Expository Writing Program 208. Sophia Roosth, Associate Professor, Gallatin School of Individualized Study 209. Andrew Ross, Professor, Social and Cultural Analysis

- Jess Row, Clinical Professor, English

- Everett Rowson, Emeritus Professor, Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies 212. Martha Rust, Associate professor, English

- Lara Saguisag, Associate Professor, Teaching and Learning

- Avgi Saketopoulou, NYU Postdoctoral Program in Psychotherapy and Psychoanalysis 215. María Josefina Saldaña-Portillo, Professor, CLACS and the Department of Social & Cultural Analysis

- Michael Salgarolo, Faculty Fellow, Department of Social & Cultural Analysis 217. Zach Samalin, Assistant Professor, English Department

- Sabrina Sanchez, Administrative Aide, Office of the Provost

- Alex Santana, CAS ’14 Alum, currently The Latinx Project at NYU 220. Suroor Seher Gandhi, PhD candidate, GSAS

- Camille-Mary Sharp, Faculty Fellow, Program in Museum Studies 222. Normandy Sherwood, Clinical Associate Professor, Expository Writing Program 223. Mari Shiratori, PhD Candidate, GSAS Biology Department

- Habibat Shittu, Student Success Specialist, Office of Student Success 225. Ella Shohat, Professor, Art and Public Policy

- George Shulman, Professor Emeritus, Gallatin School

- Dina M. Siddiqi, Clinical Associate Professor, Liberal Studies

- Denise Ferreira da Silva

- Nikhil Pal Singh, Professor of Social and Cultural Analysis and History 230. John Victor Singler, Professor Emeritus, Linguistics

- Laura Slatkin, Professor, Gallatin

- Shanté Paradigm Smalls, Associate Professor, Department of Art & Public Policy 233. Carol Anne Spreen, Associate Professor, ASH, Steinhardt

- Sreshtha Sen, Clinical Assistant Professor, EWP

- Robert Philip Stam, University Professor based in Cinema Studies 236. Juliet Stanton, Associate Professor, Linguistics

- Justin Stearns, Professor of Arab Crossroads Studies, NYUAD

- Ruby Steedle, researcher, Cash Transfer Lab

- Corinne Stokes, Senior Lecturer of Arabic, Arabic Studies Program 240. Lisa M. Stulberg; Associate Professor; Applied Statistics, Social Science and Humanities; NYU Steinhardt

- Pacharee Sudhinaraset, Assistant Professor, English

- Helga Tawil-Souri, Associate Professor, MCC & MEIS

- Diana Taylor, University Professor, NYU

- Sonali Thakkar, Assistant Professor, Dept. of English

- Madina Thiam, Assistant Professor, History

- Sinclair Thomson, Associate Professor, History Department

- Simón Trujillo, Associate Professor, English

- Thuy Linh Tu, Professor, SCA

- James S. Uleman, Professor Emeritus, Psychology, FAS

- Benjamin Wainwright, Program Coordinator, NYU Grossman School of Medicine 251. Yijun Wang, Assistant Professor, history

- Lia Warner, Alum (Gallatin ‘21 and GSAS ‘23), Reference Associate, Division of Libraries 253. Bryan Waterman, Associate Professor, English

- John Waters, Clinical Associate Professor, English and Irish Studies

- Andrew Weiner, Associate Professor, NYU-Steinhardt Dept of Art and Art Professions 256. Barbara Weinstein, Silver Professor of History

- Jerome Whitington, Clinical Assistant Professor, Gallatin School of Individualized Study and Liberal Studies

- Elizabeth Witwer, Research Manager, Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development

- Susanne Wofford, Professor, English and Gallatin

- Amy Zhang, Anthropology, FAS

- Angela Zito, Associate Professor Anthropology & Religious Studies

(Signatories as of February 12, 2024, in alphabetical order)

CC: Debra Furr-Holden, Dean of the School of Global Public Health

Sherry Glied, Dean of the Wagner School of Public Service

Allyson Green, Dean of the Tisch School of the Arts

David K. Irving, Chair, T-FSC

Jack Knott, Dean of the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development Jelena Kovačević, Dean of the Tandon School of Engineering

Antonio Merlo, Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Science

Noelle Molé Liston, Chair, C-FSC

Julie Mostov, Dean of Liberal Studies

Jason B. Pina, Senior Vice President for University Life

Rafael Rodriguez, Associate Vice President and Dean of Students

Victoria Rosner, Dean of the Gallatin School for Interdisciplinary Studies

Fountain Walker, Vice President of Global Public Safety

Author: David Ludden

Global Asia time/space

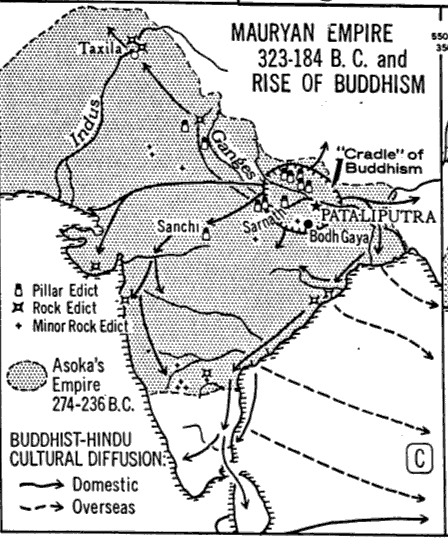

- The very long first millennium, from ancient Greeks to medieval Mongols, is the formative epoch for Global Asia time-space, when societies, cultures, and political economies all around Eurasia took shape. People transformed spaces all around Eurasia with mobility that circled around the Central Steppes and Southern Seas. Classical ancient civilizations with canonical histories in separate, self-contained fictional territories were produced by transformative mobile forces traveling that epochal time-space.

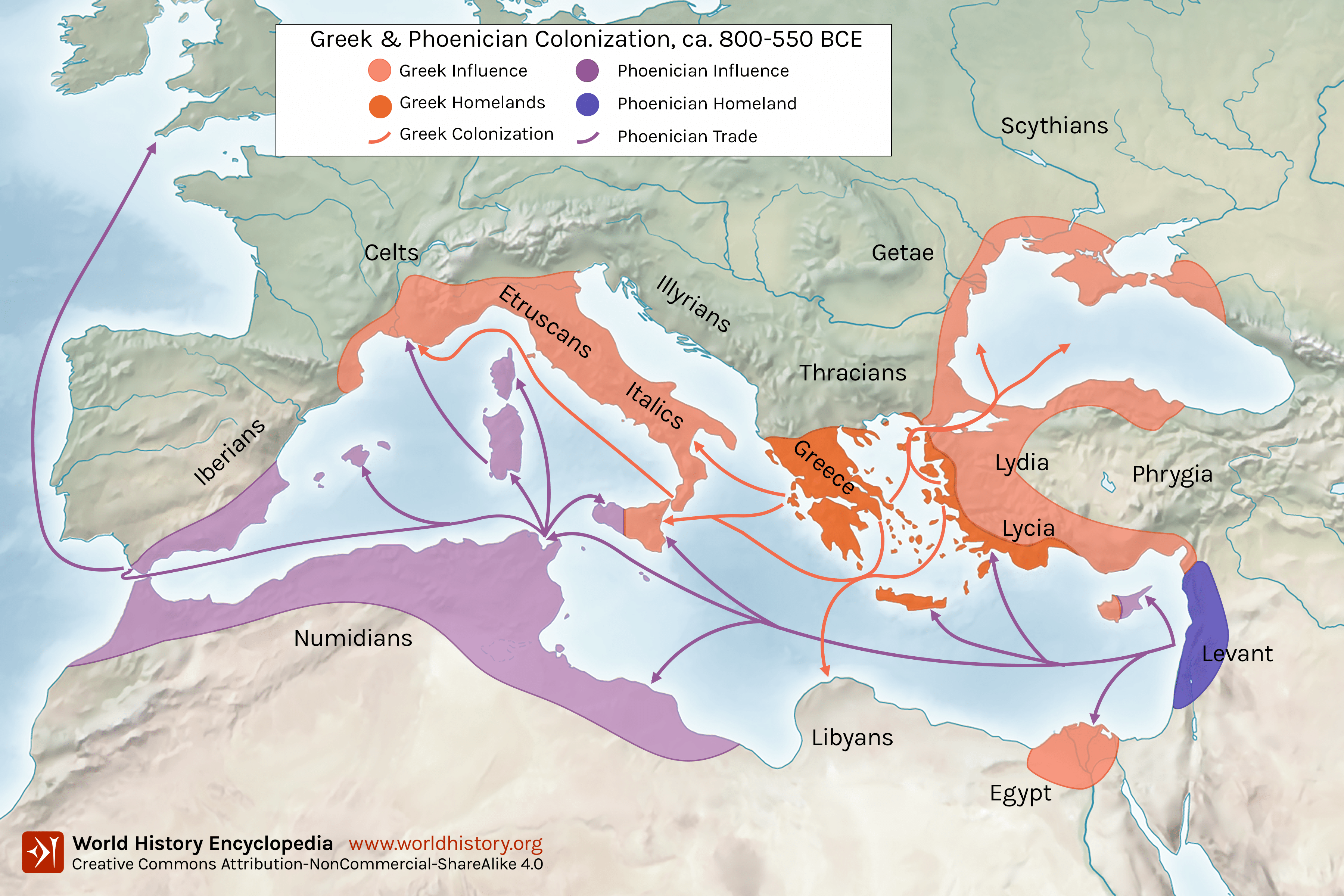

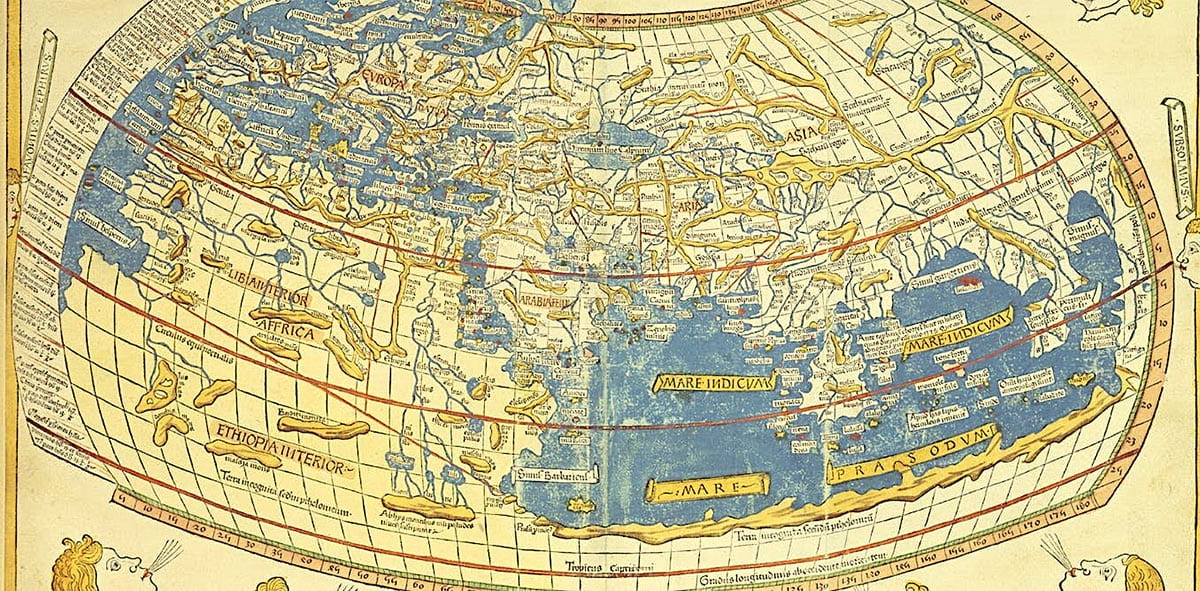

- Ancient mobility shaped distant territories. All major religions illustrate that process; so do pandemics that traveled slowly in ships and caravans from East and South West Asia to sicken Roman armies and workers and help unravel the Roman Empire. Ptolemy and The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea record known ancient spaces of Afro-Eurasia connectivity.

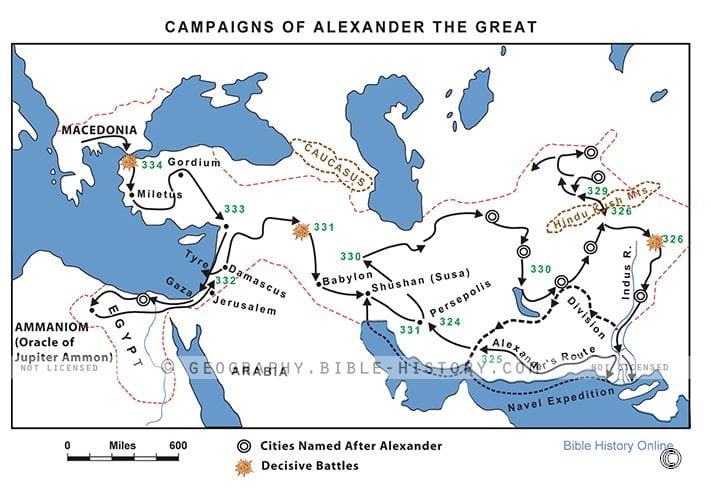

- Asian circuits of mobility expanded dramatically overland during a millennium after the fall of Rome. This transforming of space around Eurasia began with Turkic migrations (500s) and peaked with Mongol (1200s) imperial armies riding and settling west from Mongolia as far as Ukraine and the Balkans. Meanwhile, Arab armies, merchants, and settlers traveled from the arid southwest along ancient Greek and Roman routes from Spain to the Steppe (600-700s), where Caliphate troops defeated armies from Tang China at the Talas River, in 751, at the hinge of overland mobility.

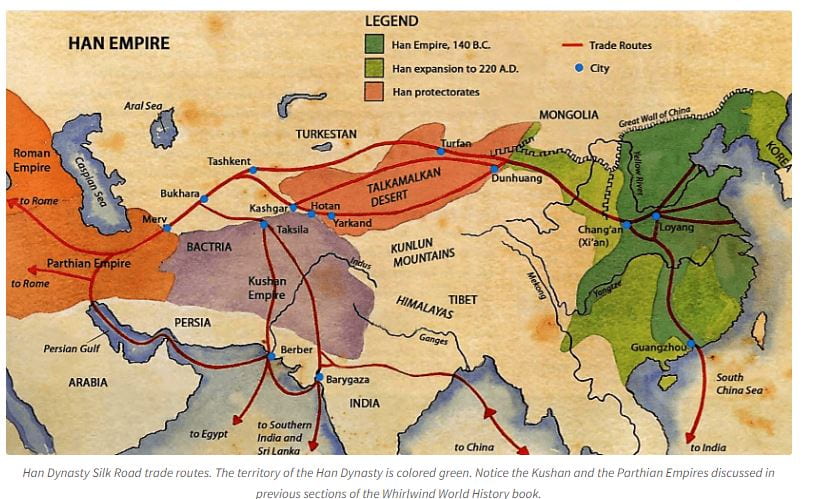

- Overland mobility propelled overseas mobility, as more and more ships sailed routes spanning Tang China and Abbasid Persia. One telling ship has been found that was built in the West, filled with Chinese porcelain made for export, bound for Persia, and sunk off Sumatra near Belitung Island, around 830. Foreigners living in the Tang port of Guangzhou included Muslims, Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians from the West.

- During warmer centuries (900-1200), expanding agrarian productivity propelled commercial mobility in southern seas, as the weight of Asian populations shifted south into more fertile rice-growing lands, feeding imperial territories along the coast in South (Cholas), Southeast (Sri Vijaya), and East (Sung) Asia. More and more spices, cotton, silks, and porcelain sailed from India and China to the Abbasid West; more Arab and Jewish merchants sailed east and south to settle in India and East Africa; more Tamil and Gujarati merchants sailed East to set up shop in Southeast, East, and Far East Asia.

- In the Far West, Egypt and Palestine had connected Roman consumers to the Asia trade. After the Fall of Rome, Arab merchant-warriors seized all the connective spaces. Increasing Asia trade then produced increasing profits in Arab lands (recorded by tenth century Cairo merchants), and rulers in the north Mediterranean launched Crusades, in 1092, fighting for Palestine.

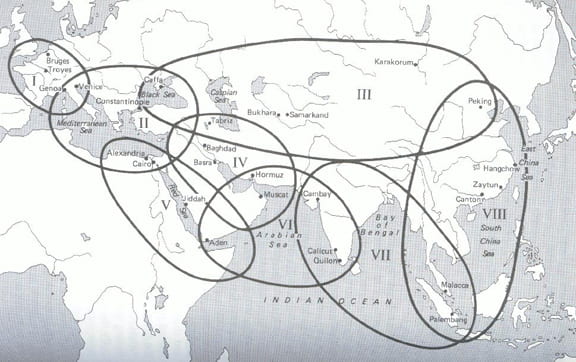

- Mongol imperial expansion (1200-1300s) combined massive military force with compliant commercial capital to expand all kinds of mobility across the Steppe into the Northwest (around the Caspian, Ukraine, Crimea, and Black Sea), and into South (Indo-Persia), East, Southeast, and Far East Asia. Mobile Mongol imperial territory tied coastal regions into inland networks of mobility to expand inland and overseas travel and trade from the Far East to Far West, all around the Steppe and Southern Seas, and into the Black Sea. Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta traveled those expansive mobile spaces mapped by Janet Abu-Lughod as a series of “circuits” in what she called a pre-modern Eurasian “world system.”

- Black Sea ports became connectors for the Asia trade traveling steppe routes controlled by the Golden Horde. Ships heading south from Crimea delivered riches to Mediterranean consumers and investors, most of all in Venice, where diverse Asian goods and slaves arrived in Venetian ports and traveled around Europe. Bubonic Plague came that way (1347) to kill up to half the European population and begin the unraveling of feudalism.

- Post-Mongol imperial territories in the West (Ottomans and Safavids), East (Ming and Qing), and South (Delhi Sultans and Mughals) arose in spaces where expansive mobile Mongol strategies and technologies for military domination acquired finance from commercial investors and systematic taxation. Interwoven imperial territories across Eurasia diversified, refined, and elaborated strategies of commercial militarism combining military power with commercial interests at unprecedented levels of scale and intensity, dramatized in grand imperial capital cities.

- A trend that became modern began with Mongols: imperial powers mobilized massive military force to expand and protect market networks and investment opportunities, increasing all kinds of mobility. The trend began in 1220, when Chinggis Khan conquered Khwarazm, in the western steppe, at the hinge of overland mobility, where he laid spatial foundations for the world’s largest commercial territory, a model for the future.

- Expanding mobile inland territory embraced seaports to increase capital accumulation in expanding spaces of military commercialism from Ottoman Anatolia, to Mughal Surat and Bengal, to the Ming/Qing Yangtze and Pearl River deltas.

- When Ottomans conquered Black Sea ports, in the 1450s, Renaissance Venetian merchants sailed West to find other routes East. Europeans then sailed all the oceans, building and conquering ports, producing global networks of seaborne mobility, where the “Columbian Exchange” of goods, people, and disease traveled among seacoasts around the world, boosting littoral productivity and commerce from the Cape of Good Hope to Japan.

- Europeans joined the expanding Asian sea trade, among post-Mongol inland territories where coastal productivity enriched and expanded overseas trade. After 1500, Europeans accelerated that trend and connected it to seacoast ports on all the continents; it has continued to the present day.

- Europeans entered Asian coastal conflicts, where territorial claims by sailing warriors, called pirates, had swarmed around ports and mingled with inland politics for centuries, notably in Sri Vijaya, Malacca, and Japan. Europeans increased armed conflict on the coast and at sea globally.

- Inland and overseas spaces interweave on the coast: for 450 years after 1400, in the age of sail, increasing trade and gunpowder militarism combined with investments by farmers, merchants, artisans, and merchants to boost productivity and conflict around Asian ports where ships growing in size and number carried goods and services for consumers and along the coast and around the world.

- Seaport coastal environments became distinctively dynamic, culturally, economically, and politically, with more diverse European settlers, more Eurasians, more import-export businesses, and more financial services for trade, taxation, and production. More numerous, wealthier, belligerent Europeans increased demand on the coast for ship- and port-building and related services: multilingual, intercultural, military, and diplomatic.

- Inland military commercialism met overseas commercial militarism around ports: expanding European territorial ambitions to control routes through inland commercial spaces where imperial taxation also required financing for military, economic, and diplomatic resources provided financiers on the coast with investment opportunities and increasing commercial capital accumulation around ports from Cape Town to Edo, in the coastal heartlands of global commercial capitalism.

- Eurasian imperial territory evolved on the coast combined inland and overseas imperial status ranks, rituals, power relations, and economic interests, all intricately entangled. In that context, there was very little resistance around seaport to the increasing power wielded by Dutch, French, and English companies expanding their control of inland mobility ater 1750.

- Coastal Eurasian imperial territory conquered inland space with increasing force, after 1800, as industrialization increased the mobile coercive power of armies backed by Euro-American governments extending their imperial territories into Asia. By the 1850s, white Christians from Europe and the US occupied highest ranks of status, command, control, and wealth in imperial territories extending inland from Asian ports on the coast.

- Imperial territory became Eurocentric and global after 1820. Europeans commanding Eurasian armies conquered inland spaces that industrial infrastructure locked into iron frames of territorial mobility with railways and steamships speeding inland Asia through ports and global networks where Euro-American people and places held top imperial ranks.

- The intensity of imperial control over mobility increased, as discipline, surveillance, punishment, evaluating, measuring, mapping, and regulating exerting ever more control over mobile space, exemplified by the conquest of steppe nomads by imperial Russia and China, of natives in Australia and the Americas, and of mobile cultivators all over Asia.

- Imperial modernity covered the globe by 1920, dividing Asia into three macro-regions, based on the time/space of European imperial ascendancy, which began in the South, moved East, and finally embraced the West.

- Unlike the Americas, Africa, and Australia, Asia did not host any major European settler colonies during the expansion of Euro-American imperial supremacy, and the ongoing and very long spatial histories of Eurasian connective became dynamic force forming and transforming spaces of imperial modernity

- Resistance in the interior — warrior regimes connect to the West via the steppe and Indo-Persia. Survival from migrations in all directions. Aspiration upward mobility in imperial ranks, particularly in sites of Eurasian imperial formations and capital accumulatioin oh the coast. And competition with aspiration b raking through the ranks as in all the earlier imperialt eritories, e.g. Mongols ….

- ons, ithy in the twentieth century.

- the formative ity interaction

- Spatial histories in each … resistance, survival, aspiration, competition …

- ethno-national Europeans

- Resist wealth and had from overseas territory privileged sites for settler mingling and mobility in overlapping Asian coastal and European overseas spaces, as secure attractive sites for mobile investors and capital accumulation, and as arenas for developing expansive imperial power relations traveling inland and overseas.

- inside Asian spaces. who mutually invested … connecting all the world’s coastal regions, where inland met overseas territorial power. relations.

- aspirations traveled inland and inland territories embraced the coast. The post-1500 combination of inland Asian and overseas European territorial power formed a spatial frame for imperial modernity marching inland for the next four centuries under competing flags of European supremacy.

- Imperial modernity became global, after 1820, as industrial mobility controlled more and more rapidly moving living space with iron frames of railways, ports, roads, cables, cities, and military force; imperial regimes on all continents channeled increasingly productive resources up spatially organized ranks of wealth and power; and as increasing global productivity disfigured nature and launched climate change.

- Imperial modernity has new global forms and old spatial dynamics. As mobility expand, over millennia, territorial controls over mobility also expand; they also intensify, as more people in more places exert more control over more territorial resources. Imperial territory became a resilient, adaptable space form of social power relations traveling and working to establish and maintain interdependent status ranks among people who exert power down the ranks and channel rewards upward. These dynamics of imperial territory appear in Global Asia from ancient; they persist and change across regimes over centuries, now in the world of nations.

- Asian ports acquired territorial privilege in imperial modernity, which traveled inland from ports and privileged people and places according to their strategic value in the expansion and stability of imperial territory. Railways and later transport and communication infrastructure privileged the ports connecting inland and overseas imperial territory for for all kinds of investments and as homes for all kinds of imperial investors. . , is most strategic places on its routes of mobile expansion. The top 10 richest cities in Asia are Tokyo, Shanghai, Beijing, Seoul, Mumbai, Osaka, Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Taipei and Singapore.

- ty spaces following the old pattern, spatial ranks of empirePeople have control in proportion to rank (per capita wealth is a good marker). with higher status have acquire assets and scope to improve their status in proportion to rank. spatially, and, at the same time, intensifies ed in scale as mobility has sped up more dramatically than ever before since 1850, propelled by social power relations on imperial spaces where people and places enjoy livelihood assets in proportion to their status imperial ranks. resistance, survival, aspiration, competition.

- port cities, where all forms of capital accumulated along routes of inland and overseas mobility. Imperial investments in ports and railways produced port city centers of wealth and power inside imperial territories aspiration … investment … competition … y, anchored global seaborne mobility, cities whose power relations organized . formed by railways tied to ports hosting massive ships GLOBAL TERRITORY …. 1880s

- Ports became global cities .Global mobility.. imperial aspirations Meiji Period (1868-1912). Japan has the most ports per land area of any political territory in the world. ‘s industry was dramatically transformed, creating a better economy. Some of the reforms included new railroads to join all four major islands, shipping lines, telegraph and telephone systems, and deep water harbors to allow bigger ships. conflict…

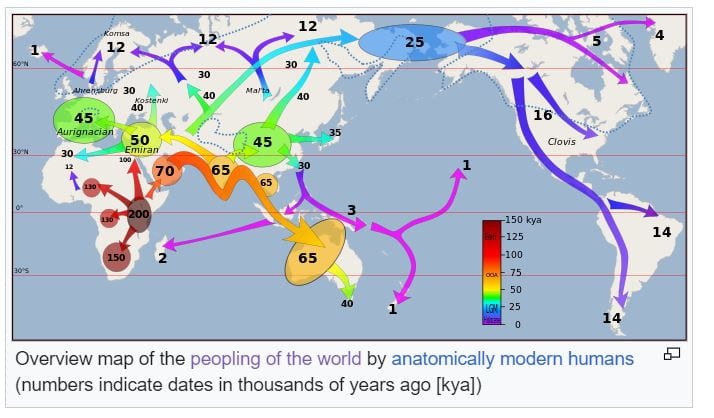

Visualizing Early Human Mobility

List of first human settlements (from Wikipedia)

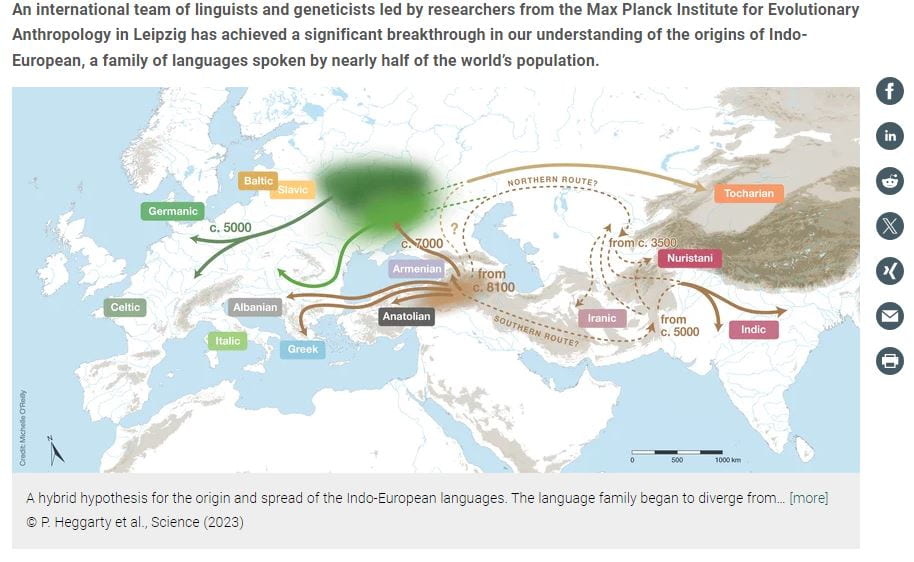

Linguistics and genetics combine to suggest a new hybrid hypothesis for the origin of the Indo-European languages.

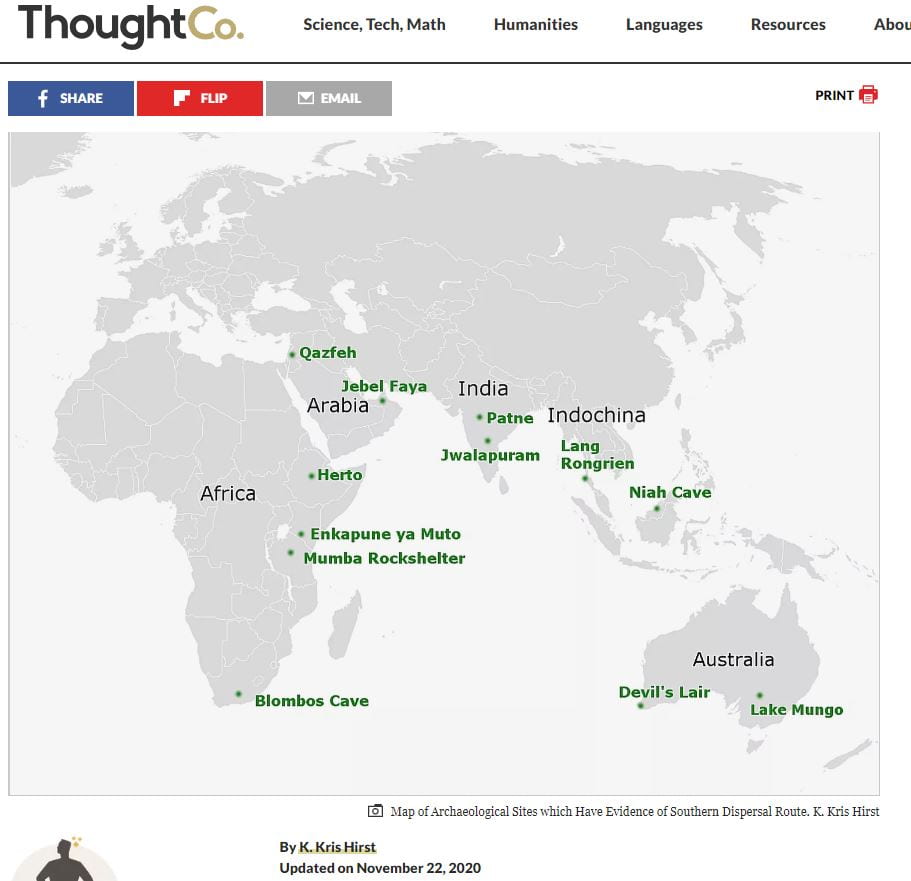

The Southern Dispersal Route refers to a theory that an early group of modern human beings left Africa between 130,000–70,000 years ago. They moved eastward, following the coastlines of Africa, Arabia, and India, arriving in Australia and Melanesia at least as early as 45,000 years ago. It is one of what appears now to have been multiple migration paths that our ancestors took as they left out of Africa.

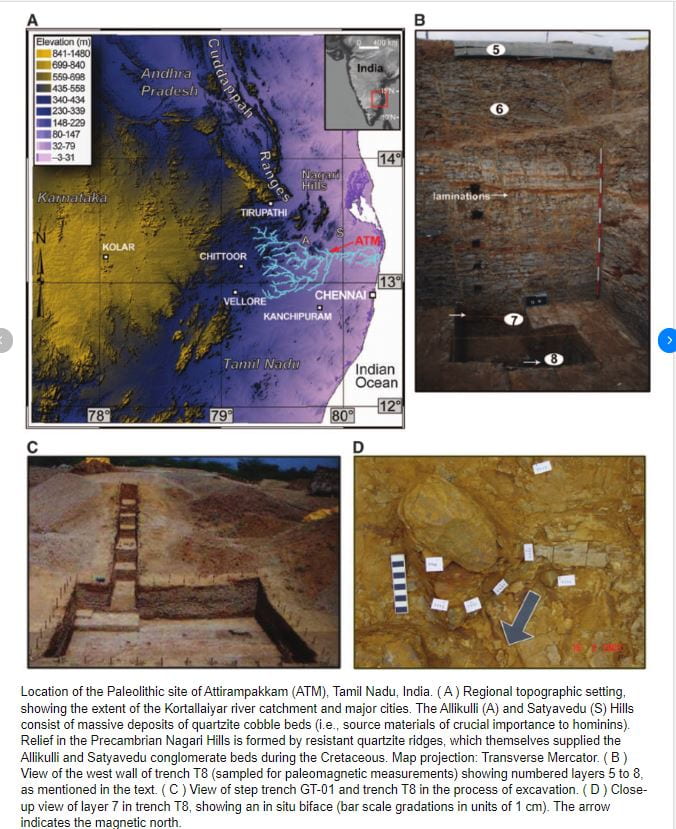

Akilesh, K., et al. “Early Middle Palaeolithic Culture in India around 385–172 Ka Reframes Out of Africa Models.” Nature, vol. 554, 2018, pp. 97–110.

Luminescence dating at the stratified prehistoric site of Attirampakkam, India, has shown that processes signifying the end of the Acheulian culture and the emergence of a Middle Palaeolithic culture occurred at 385 ± 64 thousand years ago (ka), much earlier than conventionally presumed for South Asia.

New insights into the origin of the Indo-European languages

Published online by the Max Planck Institute

JULY 27, 2023

Original publication

Paul Heggarty, Cormac Anderson, Matthew Scarborough, Benedict King, Remco Bouckaert, Lechosław Jocz, Martin Joachim Kümmel, Thomas Jügel, Britta Irslinger, Roland Pooth, Henrik Liljegren, Richard F. Strand, Geoffrey Haig, Martin Macák, Ronald I. Kim, Erik Anonby, Tijmen Pronk, Oleg Belyaev, Tonya Kim Dewey-Findell, Matthew Boutilier, Cassandra Freiberg, Robert Tegethoff, Matilde Serangeli, Nikos Liosis, Krzysztof Stronski, Kim Schulte, Ganesh Kumar Gupta, Wolfgang Haak, Johannes Krause, Quentin D. Atkinson, Simon J. Greenhill, Denise Kühnert, Russell D. Gray

Language trees with sampled ancestors support a hybrid model for the origin of Indo-European languages

Science, 28 July 2023, DOI: 10.1126/science.abg0818

Colonies — an idea that seems to be prevalent only for/in Greco-Roman settlement mobility before European overseas expansion

The Achaemenid Empire at its greatest territorial extent, under the rule of Darius the Great (522–486 BC) — with Royal Road and Central Places

Empire and Colony

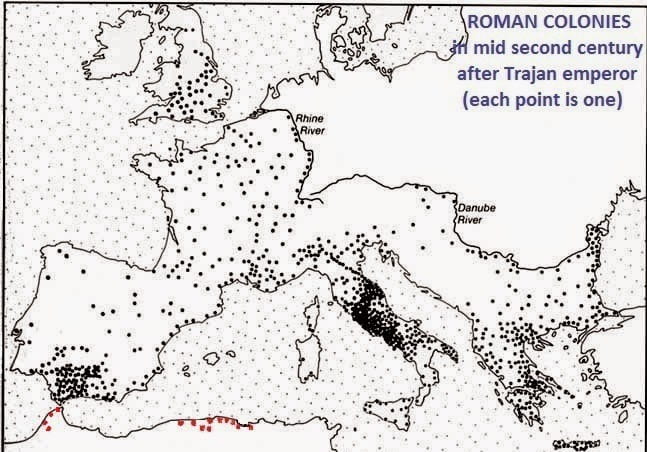

The territorial history of Global Asia involves many centuries of interaction among empires and colonies; that history underlies the violence of national state territory today, in our world of imperial modernity and US empire. All national state territories have been formed over centuries by accumulating settler colonies woven together by imperial authorities. Accumulating, overlapping, and conflicting settler and imperial territorial claims produced local conflicts, global wars, international law, and inequity enforced by colonial and imperial elites in the world of nations.

Imperial territories, in many shapes and sizes, dominate territorial history, because they create enduring archives and infrastructure. At any scale, in any cultural milieu, empire is a territorial process, a dynamic, mobile, territorial formation, extending outward into frontiers — typically with military force — penetrating down ranks of wealth, power, and authority from cities to towns to villages, forming social power relations that channel wealth and status up the ranks toward a central apex. Potentially embracing inequitably vast social and cultural diversity, empire has no fixed boundary, but limits and frailties imposed by cost of maintaining the upward flow of capital accumulation. Strengthening empire means expanding, deepening, and securing power to move assets upward toward the center; challenges to that control increase the cost and potentially weaken imperial power.

A colony is a territory where a group of people have moved to settle in a space occupied by other people. Colonies of settlers have come from elsewhere (at some point in the past); they are transplants, like colonies of bacteria in a host medium. They can likewise interact with the host in many ways: they can mingle and mix, dominate, submit, or remain separate nd marginal. Over the centuries, societies have grown as colonies of settlers arrive in various patterns traveling spaces of mobility expanding in scale over time. All localities begin with settlers arriving. Social space is typically inscribed somehow by the settler sequence. Strategic places on routes of mobility become specialized sites for settlers who live in in mobile spaces where towns and cities provide their homes and livelihoods. Its design as a place for mobile settlers makes urbanism a paradigmatic colonial process.

Colony-empire relationships are ancient, ongoing, complex, dynamic, multi-faceted, and hotly contested. Early-modern overseas European colonies and subsequent colonial conquest currently appear as the singular dominant model for colony-empire relationships in the Americas, Asia, and Africa, where colonialism and imperialism represent contrasting ways to describe Western domination, focused respectively on culture [Weber] and political economy [Marx].

to be continued — work in progress …

in the age of anti-colonial nationalism, when native cultures in colonial host environments.

f migrant settlers inside tions from omake that assumption, and when imperial troops form colonies, it clearly makes sense, as it did in ancient Romans and Mongol colonies . Colonies have diverse imperial connection. Countless migrant settlers have formed colonies in distant places: nomads, farmers, missionaries, merchants, artisans, and many others have formed culturally distinct territories in many spaces occupied by other cultures. That kind of settler mobility, settlement, and colony formation accumulates historically to produce most human environments, including all major cities.

At the same time, colonies have also served and developed inside empires. Empires have grown and strengthened by incorporating colonies into imperial ranks to augment the flow of wealth, power, and authority up the ranks. Colonies can also become unwitting imperial territories and still cling to other identities; they can begin as tools of empire, succeed or fail in that capacity, and develop opposing, independent agendas, which can fragment imperial territory.

Empires fall apart when constituent colonies become imperial territories internally strong enough to refuse to obey old imperial agendas and to independent control of their own resources.

wealth, power, and authority. That range of possibilities populated Global Asia …. ancient times to the present. . . … to be continued …. the world of mobility and settlement around the Central Asian Steppes and Sare evident historically. Some examples illuare useful. are host environments, mingled home to elsewhere. in foreign countries in recent history. , the mobility of many groups across state borders of businesses, missionaries, workers, students, and others across e business transnational businesses, missionary n call it into. on the frontier. That assumption Many colonies colonies Thave various kinds ofThe relationship idea of colonialism implies malignant a colonial process understood as invasive and pathogenic. ……… to be continued …. pandemic pathogens; specifically, in Africa and Asia, where European colonies formed empires, by extending their power forcefully outward, spatially, with military conquest, and downward vertically, with various forms of state power, to create modern state territories, where social movements emerged among people who identified themselves as representing the original native host medium invaded and conquered by colonial foreigners.

Empire and colony have acquired their distinctive contemporary identities in popular and academic discourse as ideas formed in the modern world of national states, where every nation has empires and colonies in its past and must work to construct itself, by contrast, as a cultural space of belonging with a permanent organic heritage inside its homeland.

That same contrast separates the idea of the nation from imperialism and colonialism, which have a more elaborate academic opposition.

Imperialism is an idea identified with Marx, Lenin, and the communist critique of capitalism: in that view, imperialism can continue after the official end of empires, because imperialism is about economic exploitation and imposed inequity rather than being a specific political form.

Colonialism, on the other hand, is identified with Weber and Cultural Studies. It is the foreign occupation of cultural territories where foreigners have inserted and reproduced their economic and cultural power inside a native cultural space. Foreign cultural values, languages as well as economic interests and political systems were imposed upon peoples who must free themselves of that foreign domination, or contamination, to become truly self-ruling and sovereign. Nations thus emerge as natives rising up to overcome and expel colonialism. The invasive species analogy is useful here, along with ideas of ecological survival, preservation, and restoration.

The academic opposition of empire/imperialism and colony/colonialism is a Cold War construct ………..ng these two strands together can begin by noting that colonies form imperial territories that expand with the multiplication and integration of networks among imperial colonies …. to be continued ..

Global Asia: Intro1

Global Asia:

Mobility, Territory, and Imperial Modernity

Intro 1

People on the move have made and remade human environments for millennia, by seeking, finding, and building places to call home, raising borders around cultures and peoples, investing in territory to include all kinds of things that travel with people on the move, transforming and demolishing old habitats, and moving on. As the scale of mobility has increased, over centuries, so has the scale and intensity of territorial control. That dynamic interaction continues to unsettle and reconfigure historical space, and has always been powerful in Asia, travelling around steppes and seas, from ancient times, then circling the globe, after 1500. The histories of Global Asia that we explore in this book serve to illuminate the contingent temporality of those borders on maps that separate spaces and places of all shapes and sizes to conceal the mobility of historical space transforming the world we live in. [Intro 2]