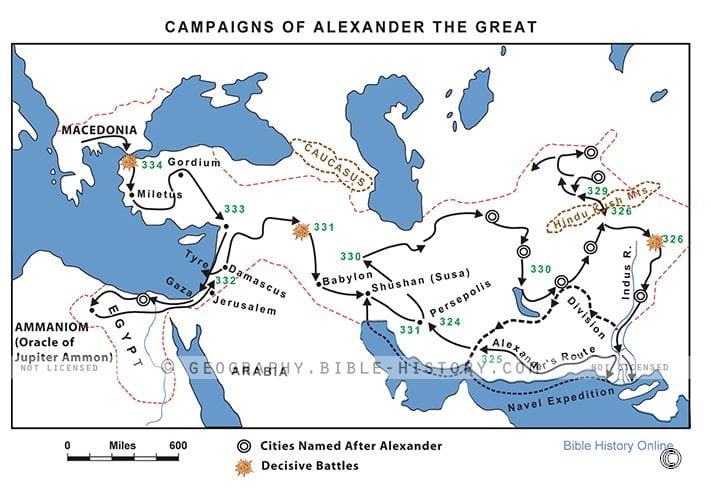

- The very long first millennium, from ancient Greeks to medieval Mongols, is the formative epoch for Global Asia time-space, when societies, cultures, and political economies all around Eurasia took shape. People transformed spaces all around Eurasia with mobility that circled around the Central Steppes and Southern Seas. Classical ancient civilizations with canonical histories in separate, self-contained fictional territories were produced by transformative mobile forces traveling that epochal time-space.

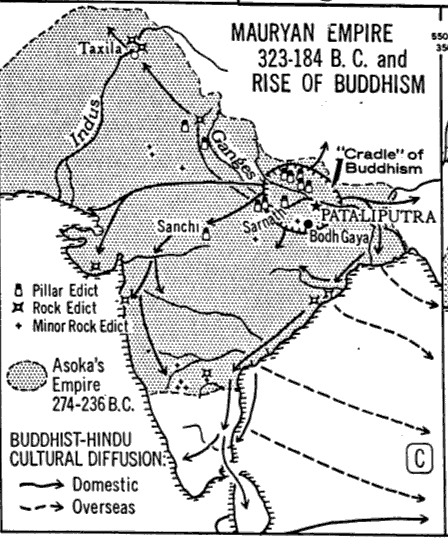

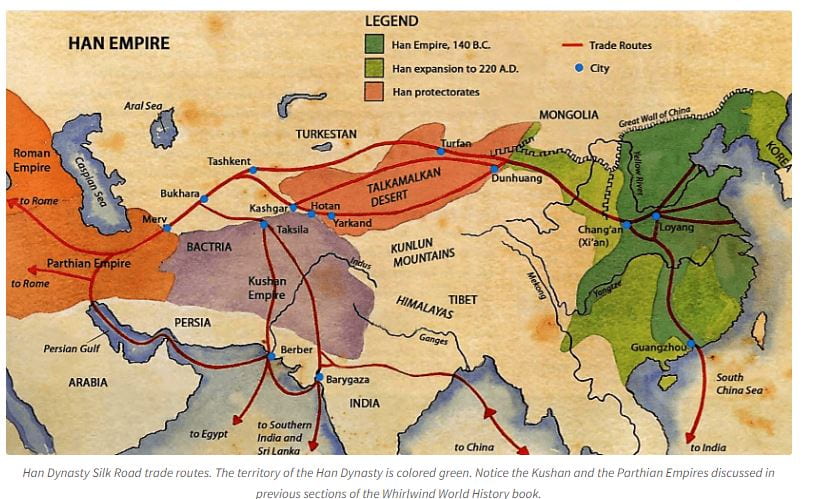

- Ancient mobility shaped distant territories. All major religions illustrate that process; so do pandemics that traveled slowly in ships and caravans from East and South West Asia to sicken Roman armies and workers and help unravel the Roman Empire. Ptolemy and The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea record known ancient spaces of Afro-Eurasia connectivity.

- Asian circuits of mobility expanded dramatically overland during a millennium after the fall of Rome. This transforming of space around Eurasia began with Turkic migrations (500s) and peaked with Mongol (1200s) imperial armies riding and settling west from Mongolia as far as Ukraine and the Balkans. Meanwhile, Arab armies, merchants, and settlers traveled from the arid southwest along ancient Greek and Roman routes from Spain to the Steppe (600-700s), where Caliphate troops defeated armies from Tang China at the Talas River, in 751, at the hinge of overland mobility.

- Overland mobility propelled overseas mobility, as more and more ships sailed routes spanning Tang China and Abbasid Persia. One telling ship has been found that was built in the West, filled with Chinese porcelain made for export, bound for Persia, and sunk off Sumatra near Belitung Island, around 830. Foreigners living in the Tang port of Guangzhou included Muslims, Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians from the West.

- During warmer centuries (900-1200), expanding agrarian productivity propelled commercial mobility in southern seas, as the weight of Asian populations shifted south into more fertile rice-growing lands, feeding imperial territories along the coast in South (Cholas), Southeast (Sri Vijaya), and East (Sung) Asia. More and more spices, cotton, silks, and porcelain sailed from India and China to the Abbasid West; more Arab and Jewish merchants sailed east and south to settle in India and East Africa; more Tamil and Gujarati merchants sailed East to set up shop in Southeast, East, and Far East Asia.

- In the Far West, Egypt and Palestine had connective Roman consumers to the Asia trade. After the Fall of Rome, Arab merchant-warriors seized all the connective spaces. Increasing Asia trade then produced increasing profits in Arab lands (recorded by tenth century Cairo merchants), and rulers in the north Mediterranean launched Crusades, in 1092, fighting for Palestine.

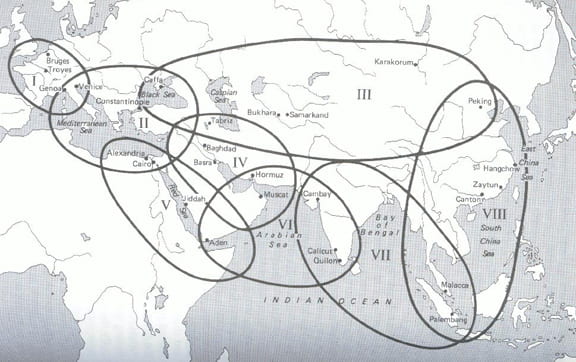

- Mongol imperial expansion (1200-1300s) combined massive military force with compliant commercial capital to expand all kinds of mobility across the Steppe into the Northwest (around the Caspian, Ukraine, Crimea, and Black Sea), and into South (Indo-Persia), East, Southeast, and Far East Asia. Mobile Mongol imperial territory tied coastal regions into inland networks of mobility to expand inland and overseas travel and trade from the Far East to Far West, all around the Steppe and Southern Seas, and into the Black Sea. Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta traveled those expansive mobile spaces mapped by Janet Abu-Lughod as a series of “circuits” in what she called a pre-modern Eurasian “world system.”

- Black Sea ports became connectors for the Asia trade traveling steppe routes controlled by the Golden Horde. Ships heading south from Crimea delivered riches to Mediterranean consumers and investors, most of all in Venice, where diverse Asian goods and slaves arrived in Venetian ports and traveled around Europe. Bubonic Plague came that way (1347) to kill up to half the European population and begin the unraveling of feudalism.

- Post-Mongol imperial territories in the West (Ottomans and Safavids), East (Ming and Qing), and South (Delhi Sultans and Mughals) arose in spaces where expansive mobile Mongol strategies and technologies for military domination acquired finance from commercial investors and systematic taxation. Interwoven imperial territories across Eurasia diversified, refined, and elaborated strategies of commercial militarism combining military power with commercial interests at unprecedented levels of scale and intensity, dramatized in grand imperial capital cities.

- A trend that became modern began with Mongols: imperial powers mobilized massive military force to expand and protect market networks and investment opportunities, increasing all kinds of mobility. The trend began in 1220, when Chinggis Khan conquered Khwarazm, in the western steppe, at the hinge of overland mobility, where he laid spatial foundations for the world’s largest commercial territory, a model for the future.

- Expanding mobile inland territory embraced seaports to increase capital accumulation in expanding spaces of military commercialism from Ottoman Anatolia, to Mughal Surat and Bengal, to the Ming/Qing Yangtze and Pearl River deltas.

- When Ottomans conquered Black Sea ports, in the 1450s, Renaissance Venetian merchants sailed West to find other routes East. Europeans then sailed all the oceans, building and conquering ports, producing global networks of seaborne mobility, where the “Columbian Exchange” of goods, people, and disease traveled among seacoasts around the world, boosting littoral productivity and commerce from the Cape of Good Hope to Japan.

- Europeans joined the expanding Asian sea trade, among post-Mongol inland territories where coastal productivity enriched and expanded overseas trade. After 1500, Europeans accelerated that trend and connected it to seacoast ports on all the continents; it has continued to the present day.

- Europeans entered Asian coastal conflicts, where territorial claims by sailing warriors, called pirates, had swarmed around ports and mingled with inland politics for centuries, notably in Sri Vijaya, Malacca, and Japan. Europeans increased armed conflict on the coast and at sea globally.

- Inland and overseas spaces interweave on the coast: for 450 years after 1400, in the age of sail, increasing trade and gunpowder militarism combined with investments by farmers, merchants, artisans, and merchants to boost productivity and conflict around Asian ports where ships growing in size and number carried goods and services for consumers and along the coast and around the world.

- Seaport coastal environments became distinctively dynamic, culturally, economically, and politically, with more diverse European settlers, more Eurasians, more import-export businesses, and more financial services for trade, taxation, and production. More numerous, wealthier, belligerent Europeans increased demand on the coast for ship- and port-building and related services: multilingual, intercultural, military, and diplomatic.

- Inland military commercialism met overseas commercial militarism around ports: expanding European territorial ambitions to control routes through inland commercial spaces where imperial taxation also required financing for military, economic, and diplomatic resources provided financiers on the coast with investment opportunities and increasing commercial capital accumulation around ports from Cape Town to Edo, in the coastal heartlands of global commercial capitalism.

- Eurasian imperial territory evolved on the coast combined inland and overseas imperial status ranks, rituals, power relations, and economic interests, all intricately entangled. In that context, there was very little resistance around seaport to the increasing power wielded by Dutch, French, and English companies expanding their control of inland mobility ater 1750.

- Coastal Eurasian imperial territory conquered inland space with increasing force, after 1800, as industrialization increased the mobile coercive power of armies backed by Euro-American governments extending their imperial territories into Asia. By the 1850s, white Christians from Europe and the US occupied highest ranks of status, command, control, and wealth in imperial territories extending inland from Asian ports on the coast.

- Imperial territory became Eurocentric and global after 1820. Europeans commanding Eurasian armies conquered inland spaces that industrial infrastructure locked into iron frames of territorial mobility with railways and steamships speeding inland Asia through ports and global networks where Euro-American people and places held top imperial ranks.

- The intensity of imperial control over mobility increased, as discipline, surveillance, punishment, evaluating, measuring, mapping, and regulating exerting ever more control over mobile space, exemplified by the conquest of steppe nomads by imperial Russia and China, of natives in Australia and the Americas, and of mobile cultivators all over Asia.

- Imperial modernity covered the globe by 1920, dividing Asia into three macro-regions, based on the time/space of European imperial ascendancy, which began in the South, moved East, and finally embraced the West.

- Unlike the Americas, Africa, and Australia, Asia did not host any major European settler colonies during the expansion of Euro-American imperial supremacy, and the ongoing and very long spatial histories of Eurasian connective became dynamic force forming and transforming spaces of imperial modernity

- Resistance in the interior — warrior regimes connect to the West via the steppe and Indo-Persia. Survival from migrations in all directions. Aspiration upward mobility in imperial ranks, particularly in sites of Eurasian imperial formations and capital accumulatioin oh the coast. And competition with aspiration b raking through the ranks as in all the earlier imperialt eritories, e.g. Mongols ….

- ons, ithy in the twentieth century.

- the formative ity interaction

- Spatial histories in each … resistance, survival, aspiration, competition …

- ethno-national Europeans

- Resist wealth and had from overseas territory privileged sites for settler mingling and mobility in overlapping Asian coastal and European overseas spaces, as secure attractive sites for mobile investors and capital accumulation, and as arenas for developing expansive imperial power relations traveling inland and overseas.

- inside Asian spaces. who mutually invested … connecting all the world’s coastal regions, where inland met overseas territorial power. relations.

- aspirations traveled inland and inland territories embraced the coast. The post-1500 combination of inland Asian and overseas European territorial power formed a spatial frame for imperial modernity marching inland for the next four centuries under competing flags of European supremacy.

- Imperial modernity became global, after 1820, as industrial mobility controlled more and more rapidly moving living space with iron frames of railways, ports, roads, cables, cities, and military force; imperial regimes on all continents channeled increasingly productive resources up spatially organized ranks of wealth and power; and as increasing global productivity disfigured nature and launched climate change.

- Imperial modernity has new global forms and old spatial dynamics. As mobility expand, over millennia, territorial controls over mobility also expand; they also intensify, as more people in more places exert more control over more territorial resources. Imperial territory became a resilient, adaptable space form of social power relations traveling and working to establish and maintain interdependent status ranks among people who exert power down the ranks and channel rewards upward. These dynamics of imperial territory appear in Global Asia from ancient; they persist and change across regimes over centuries, now in the world of nations.

- Asian ports acquired territorial privilege in imperial modernity, which traveled inland from ports and privileged people and places according to their strategic value in the expansion and stability of imperial territory. Railways and later transport and communication infrastructure privileged the ports connecting inland and overseas imperial territory for for all kinds of investments and as homes for all kinds of imperial investors. . , is most strategic places on its routes of mobile expansion. The top 10 richest cities in Asia are Tokyo, Shanghai, Beijing, Seoul, Mumbai, Osaka, Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Taipei and Singapore.

- ty spaces following the old pattern, spatial ranks of empirePeople have control in proportion to rank (per capita wealth is a good marker). with higher status have acquire assets and scope to improve their status in proportion to rank. spatially, and, at the same time, intensifies ed in scale as mobility has sped up more dramatically than ever before since 1850, propelled by social power relations on imperial spaces where people and places enjoy livelihood assets in proportion to their status imperial ranks. resistance, survival, aspiration, competition.

- port cities, where all forms of capital accumulated along routes of inland and overseas mobility. Imperial investments in ports and railways produced port city centers of wealth and power inside imperial territories aspiration … investment … competition … y, anchored global seaborne mobility, cities whose power relations organized . formed by railways tied to ports hosting massive ships GLOBAL TERRITORY …. 1880s

- Ports became global cities .Global mobility.. imperial aspirations Meiji Period (1868-1912). Japan has the most ports per land area of any political territory in the world. ‘s industry was dramatically transformed, creating a better economy. Some of the reforms included new railroads to join all four major islands, shipping lines, telegraph and telephone systems, and deep water harbors to allow bigger ships. conflict…

Month: January 2024

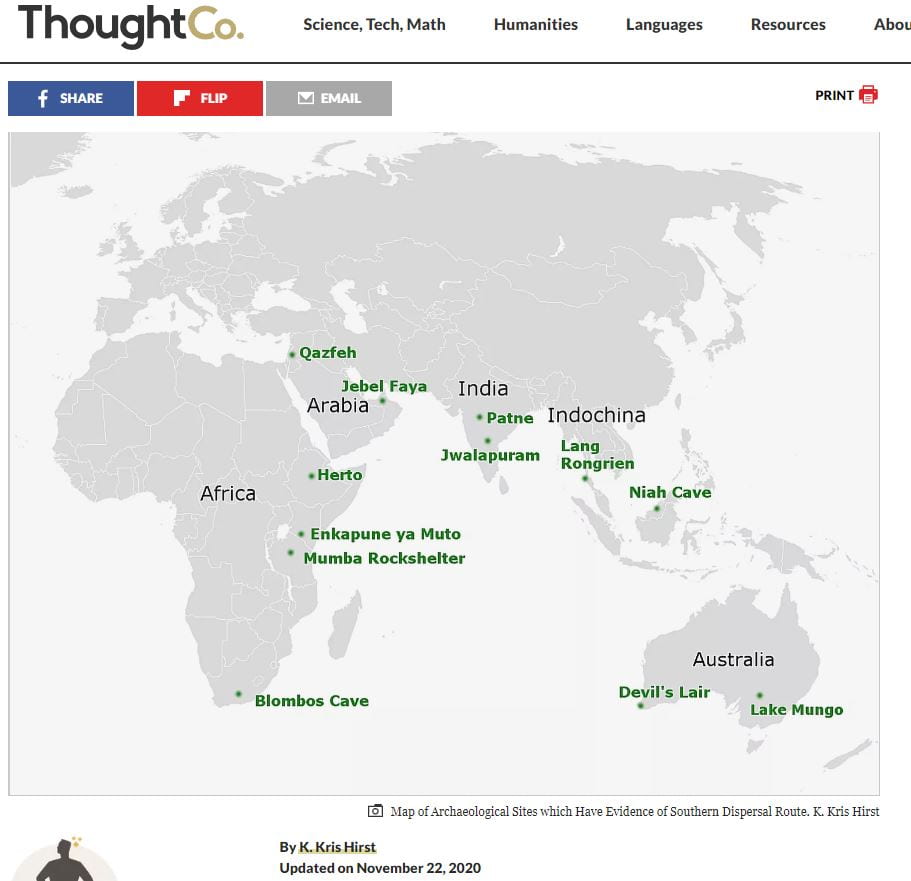

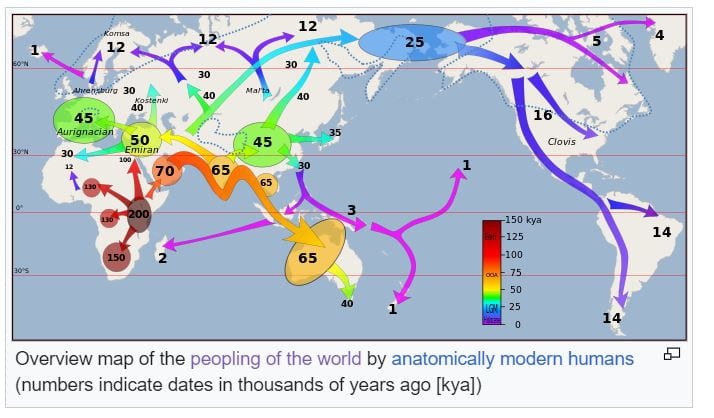

Visualizing Early Human Mobility

List of first human settlements (from Wikipedia)

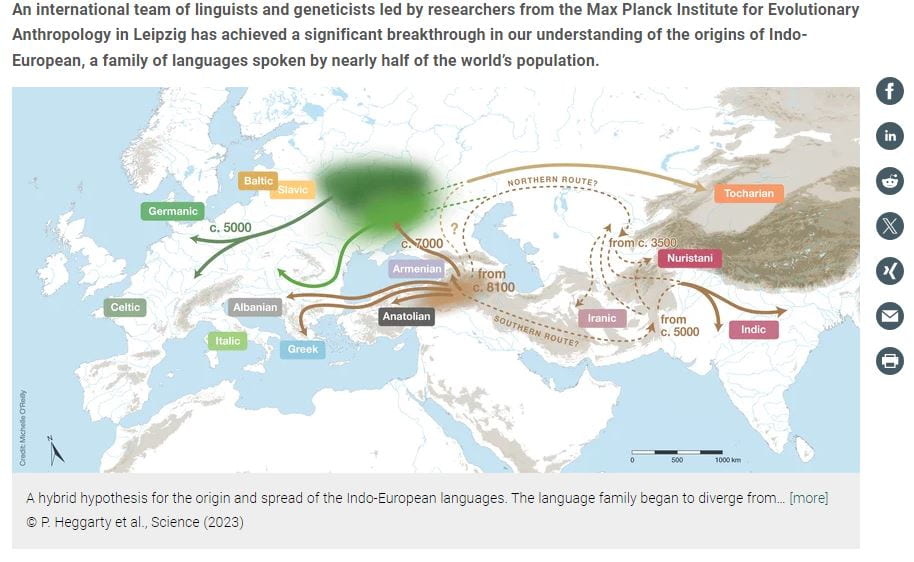

Linguistics and genetics combine to suggest a new hybrid hypothesis for the origin of the Indo-European languages.

The Southern Dispersal Route refers to a theory that an early group of modern human beings left Africa between 130,000–70,000 years ago. They moved eastward, following the coastlines of Africa, Arabia, and India, arriving in Australia and Melanesia at least as early as 45,000 years ago. It is one of what appears now to have been multiple migration paths that our ancestors took as they left out of Africa.

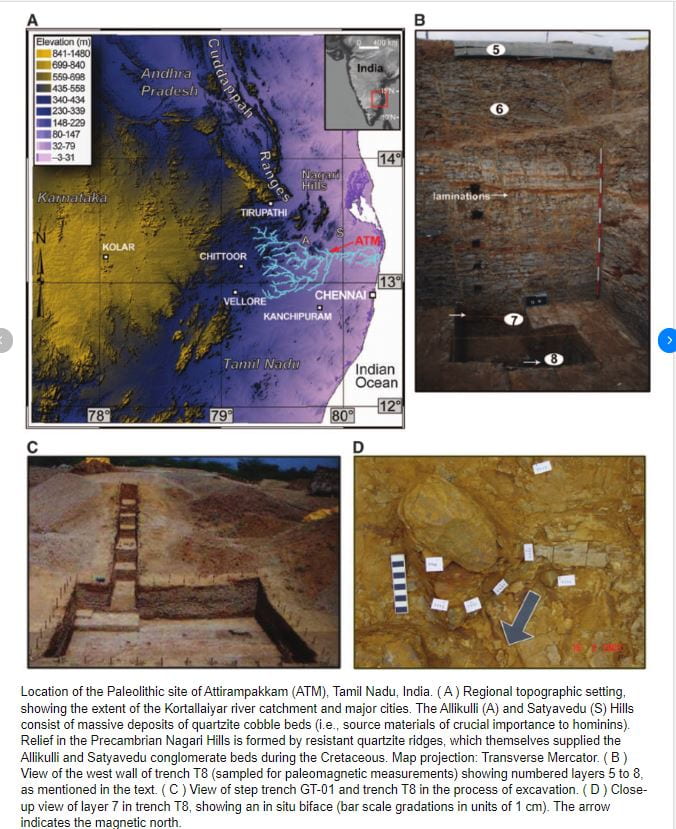

Akilesh, K., et al. “Early Middle Palaeolithic Culture in India around 385–172 Ka Reframes Out of Africa Models.” Nature, vol. 554, 2018, pp. 97–110.

Luminescence dating at the stratified prehistoric site of Attirampakkam, India, has shown that processes signifying the end of the Acheulian culture and the emergence of a Middle Palaeolithic culture occurred at 385 ± 64 thousand years ago (ka), much earlier than conventionally presumed for South Asia.

New insights into the origin of the Indo-European languages

Published online by the Max Planck Institute

JULY 27, 2023

Original publication

Paul Heggarty, Cormac Anderson, Matthew Scarborough, Benedict King, Remco Bouckaert, Lechosław Jocz, Martin Joachim Kümmel, Thomas Jügel, Britta Irslinger, Roland Pooth, Henrik Liljegren, Richard F. Strand, Geoffrey Haig, Martin Macák, Ronald I. Kim, Erik Anonby, Tijmen Pronk, Oleg Belyaev, Tonya Kim Dewey-Findell, Matthew Boutilier, Cassandra Freiberg, Robert Tegethoff, Matilde Serangeli, Nikos Liosis, Krzysztof Stronski, Kim Schulte, Ganesh Kumar Gupta, Wolfgang Haak, Johannes Krause, Quentin D. Atkinson, Simon J. Greenhill, Denise Kühnert, Russell D. Gray

Language trees with sampled ancestors support a hybrid model for the origin of Indo-European languages

Science, 28 July 2023, DOI: 10.1126/science.abg0818

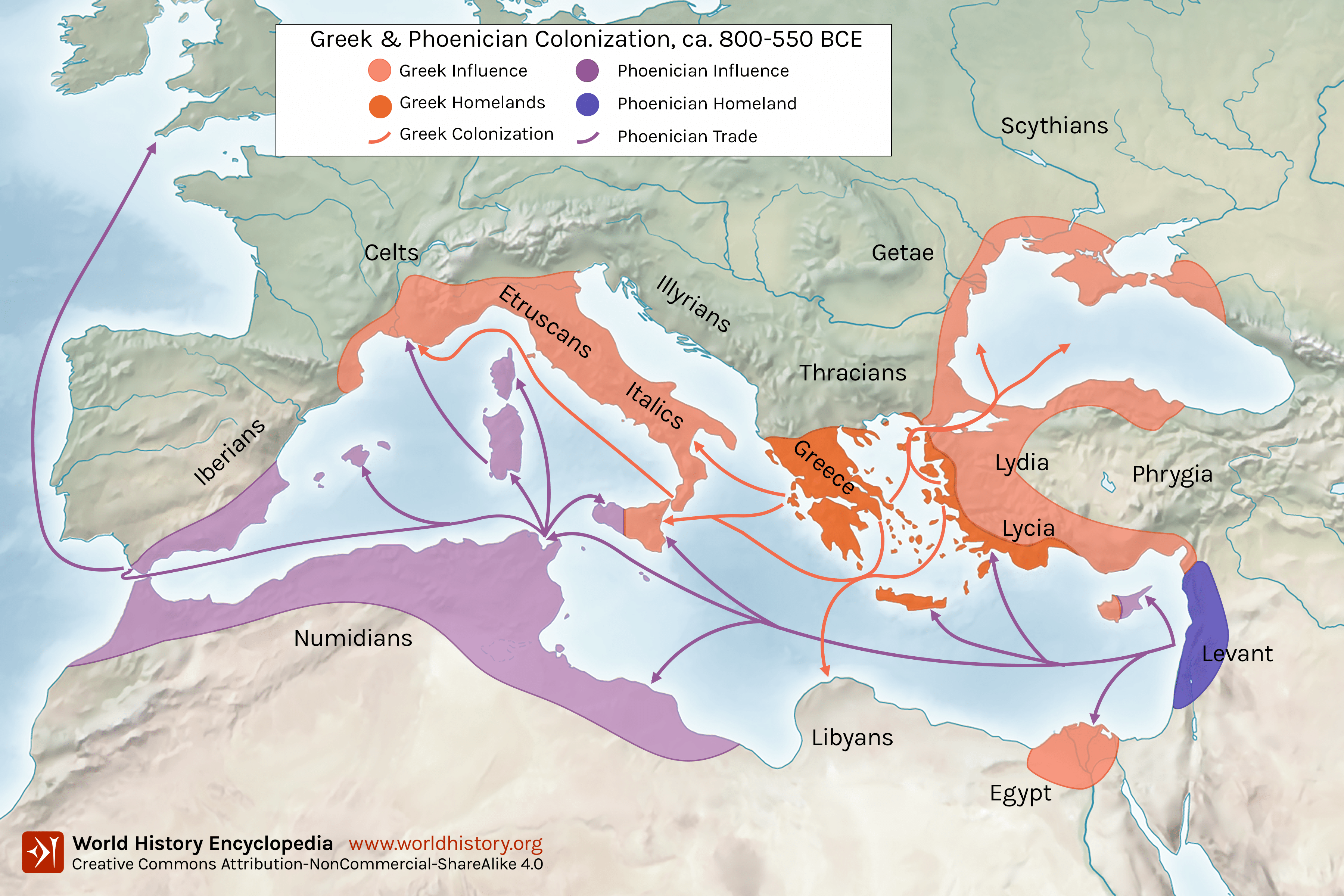

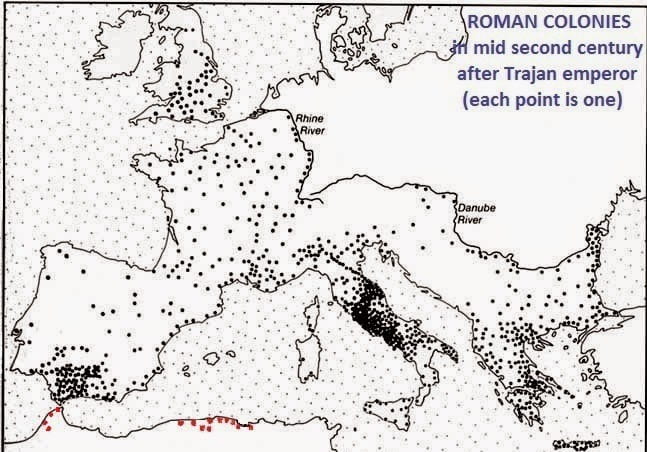

Colonies — an idea that seems to be prevalent only for/in Greco-Roman settlement mobility before European overseas expansion

The Achaemenid Empire at its greatest territorial extent, under the rule of Darius the Great (522–486 BC) — with Royal Road and Central Places