Spotlight Research Faculty

Sharon Traiberman

In the last few years, workers in developed countries have become skeptical of the pace of globalization, and policy makers have responded with increasing protectionism. My research agenda focuses on understanding which margins of adjustment are most costly for workers, why, and the ramifications of rising protectionism for workers.

In my paper, Occupations and Import Competition, I show that workers find switching occupations particularly hard. In a model of frictionless mobility, wages across occupations for otherwise identical workers should be equated. Indeed, this is the assumption of the workhorse quantitative trade models.1 However, in raw data, occupational wage differentials are large. These differences can be accounted for by the fact that comparing “otherwise identical workers” is difficult—aside from observable characteristics like age, educational background, or gender, workers can differ in unobservable factors such as their innate comparative advantage. Accumulated experience can also explain differences in wages—this is especially important for thinking about reallocation since workers who change occupations will have far less experience than the average incumbent worker.

To estimate the importance of comparative advantage, and the returns to occupational experience, for explaining wage differences, I exploit a long panel of Danish workers. I borrow tools from statistics and machine learning to group workers into different comparative advantage types. Persistence in wages over time, conditional on observable covariates and occupational tenure, can reveal absolute advantage; at the same time, differences in where workers are in the income distribution for different occupations reveals their comparative advantage. For example, a worker that is persistently in the 90th percentile of the residual distribution of an occupation has a clear absolute advantage in that job. Moreover, if the aforementioned worker is persistently in the 10th percentile of residual earnings in another occupation, they must have a comparative advantage in the first.

When looking at wage differentials, I estimate an average cost to switching occupations of 31% of income. However, over half of this cost can be explained by differences in comparative advantage and accumulated experience. That is to say, workers are reluctant to move because it is better to be a top earner in an occupation they are skilled at, then start over at the bottom of the ladder somewhere else. Nevertheless, similar looking workers still appear to leave up to 17% of their income on the table. In current work, I am continuing to explore the sources of these costs—particularly differences in major choice across college graduates.

I embed my estimates in a quantitative trade model to simulate the impact of trade frictions when workers face occupational switching costs. The model I build features frictions in moving across manufacturing and services, allowing a comparison to the existing literature,2 frictions across occupations, and input-output spillovers in the production of different goods. The input-output spillovers generate heterogeneity in the elasticity of substitution between occupations and imports: the reduction in the price of a good should lower the demand for occupations used intensively in that good, but raise demand in occupations intensive wherever the same good is used an input. This “productivity enhancing effect of trade”3 is what makes the exercise interesting: more import competition has totally ambiguous impacts on the demand for occupations, even within import-competing industries.

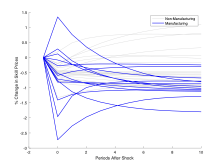

The first key result of this exercise is summarized in the figure below: adjustment of wages to a 10% change in import prices takes about 10 years, and both the biggest winners and losers from lower trade barriers are within the manufacturing sector, across occupations. My second key result is that 5% of workers see absolute declines in lifetime earnings, even though lower prices tend to make the majority of workers better off. As real wages in each occupation increase for all workers, it can be inferred that the majority of losses are incurred by inexperienced workers squeezed out of their comparative advantage occupation, rather than by experienced workers forgoing their accumulated human capital.

While this work highlights the kind of tradeoffs that workers must make when faced with import competition, it does not speak to the impact of rising protectionism. Understanding protectionism requires a model that can simulate the impact of tariffs and trade wars on global prices and factor demands. In my preliminary work, Globalization, Trade Imbalances, and Labor Market Adjustment, joint with Rafael Dix Carneiro, Joao Pessoa, and Ricardo Reyes-Heroles, we build a model where workers in different countries face costs of adjustment, prices are determined in a global equilibrium, and savings and borrowing decisions across countries lead to endogenous trade imbalances. Estimating this model has been a data-intensive undertaking, requiring us to combine micro data from several different countries. However, we plan to use our model to predict how workers in different countries will reallocate in response to a possible trade war, and the resulting effect on wages.

1 Eaton, J., & Kortum, S. (2002). Technology, geography, and trade. Econometrica, 70(5), 1741-1779.

2 Artuç, E., Chaudhuri, S., & McLaren, J. (2010). Trade shocks and labor adjustment: A structural empirical approach. American Economic Review, 100(3), 1008-45.

3 Grossman, G. M., & Rossi-Hansberg, E. (2008). Trading tasks: A simple theory of offshoring. American Economic Review, 98(5), 1978-97.