by Xandi McMahon

At a campaign speech in Gilford, New Hampshire in January 1976, while audience members gasped and laughed, Ronald Reagan announced, “In Chicago, they found a woman who holds the record. She used 80 names, 30 addresses [and] 15 telephone numbers to collect food stamps, social security [and] veterans benefits for four nonexistent deceased veterans husbands, as well as welfare. Her tax-free cash income alone has been running $150,000 a year.”[1] That woman was Linda Taylor, and she was, according to Reagan, a “welfare queen.” During the 1970s, welfare fraud had become a vastly overstated issue, and Reagan’s 1976 campaign strategy reflected the rise of a new narrative of poverty. Strongly influenced by image and racialized discourse surrounding welfare, the success of the “welfare queen” epitomized this new narrative. The American people—who had previously understood welfare recipients as primarily white and working-class, which they demographically were—now saw welfare recipients as primarily black and female.[2] The “welfare queen” image did not exist in a vacuum: it played into 2 long-held stereotypes about women, African Americans, and low-income people. In other words, the rise of the “welfare queen” narrative was both predictable and intentional. This shift in perception surrounding welfare recipients reflected the efforts of numerous politicians, as well as the structures and systems which guided them, toward three primary objectives, all of which had deep historical roots. First, coding poverty as black and female would enable the state and those in power to continue to monitor and control black and female bodies under the guise of assistance.[3] Second, it would enable people in power to incrementally and pointedly dismantle the welfare state through the support of white supremacy and patriarchy. Third, it would further perpetuate the false conception of poverty as a personal failure as opposed to an institutional, structural one. The new narrative of poverty created a non-consensual identity politics around welfare mothers, but the imposition came with one significant unintended consequence: it mobilized intersectional and radical solidarity and organizing among welfare recipients.

In The Politics of Disgust: The Public Identity of the Welfare Queen, Ange-Marie Hancock writes that “a developed democracy usually turns its attention to issues about which there is a genuine debate, but the underlying assumptions—the unquestioned consensus about certain topics—influence democratic deliberation before, during, and after a specific policy or issue debate.”[4] How did the American people collectively come to its “unquestioned consensus” surrounding poverty?

Many of the same harmful and false stereotypes about black women have persevered for centuries, and continue to inform what Hancock brands our unquestioned consensus about welfare. In 18th and 19th century America, through the legal system of slavery, white slave-owners owned black women as property, and regularly degraded and plundered their bodies. Black women would sometimes become pregnant by white men and, were also often sold into prostitution and forced to become objects of white men’s sexual conquest.[5] Out of this brutality grew the “Jezebel” stereotype: the “promiscuous, predatory, overly sexual” black woman. Accompanying the “Jezebel” stereotype were similarly erroneous and offensive stereotypes of black women, such as those of the “lazy” or “angry” black woman.[6] These were affective stereotypes: they primarily attacked black women by implying that they had too much emotion. Men’s misogynistic views toward women and their emotions infantilized women to justify the often violent control of their bodies. A seeming contradiction, the simultaneous hypersexualization and infantilization of black women served the same greater purpose of bodily control.[7]

Welfare has long been a way to police women’s bodies and sexualities. In early 20th century New York, eligibility requirements for welfare—then in the form of mothers’ pensions—were quite strict and often prevented women from joining the workforce, a detail which appeased conservative “family values” advocates. Among requirements like citizenship and evidence of destitution were “behavioral standards” for the recipients of mothers’ pensions. Although mothers’ pensions gave women a taste of independence which they had previously lacked, the “behavioral standards” very literally worked to control them. Regulations to mothers’ pensions included a “man in the house” law, which allowed social workers to investigate women’s homes to see if a man had been living there, and if one had, to subsequently bar these women from receiving aid.[8] The “man in the house” law and “behavioral standards” for pension recipients mandated the sexual regulation of women’s bodies and began a long-lasting tradition of distrusting women on welfare.[9] As Anna Marie Smith highlights in Welfare Reform and Sexual Regulation, welfare initiatives have often been “designed to advance the broader goal of patriarchal and racial population management among the poor.”[10] It is crucial here that we remember the most fundamental requirement for receiving a mothers’ pension: one needed to be a mother.

The devaluation of reproductive labor—and by extension, of motherhood—frames our understanding of the “welfare queen” image, and largely shapes welfare discourse today. Women have long held the responsibility to literally reproduce humanity: to bear and raise children. This labor, however, has not been adequately recognized for its economic value and impact on society. Capitalism was founded on the expectation that women provide reproductive and care labor for free; the lack of wages for this work has been crucial to the social subordination of women.[11] Debates about work requirements—whether or not welfare recipients should be mandated to work a certain amount in order to receive benefits—have long pervaded conversations about welfare, and crucial to these debates and our discussion of welfare is the false understanding that reproductive labor and housework are not themselves work, let alone work worth a wage.

In 1935, the creation of Aid to Dependent Children (ADC), which later became Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), essentially extended the mothers’ pension of the early 20th century.[12] AFDC, a program which largely served single white mothers, did not affect white people and people of color in the same way. As a state-run program, eligibility differed throughout the country and the “separate but equal” doctrine and Jim Crow laws prohibited black people from full participation in many states. Racism augmented the stigmatization of poverty and supported “the growing association of whiteness with moral superiority earned through the avoidance of public institutions and blackness with a deplorable reliance on the state.”[13]

In the 1960s and 70s, as television news became more and more popular, images became more and more important to the public understanding of poverty. The image of the “welfare queen” existed within the context of various other, often similarly false images of poverty. The American public and politicians have reciprocally shaped each other’s respective opinions and agendas, and both thus shaped the way legislation was created and carried out. Because images have played a large role in forming public opinion on welfare, they also play a large role in determining the response to welfare legislation and reform. During these years, the image of poverty, which had formerly been one of a rural white man and divorced or a widowed white mother, became increasingly one of an urban black mother; and the newly formed portrait was well documented in newspapers and other media outlets.[14]

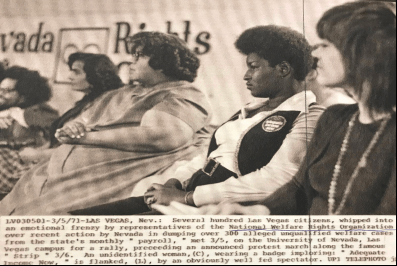

Figure 1. Photograph by unknown photographer from United Press International on 5 March 1971, found in The Daily Worker and the Daily World at the Tamiment Library.[15]

Figure 1. Photograph by unknown photographer from United Press International on 5 March 1971, found in The Daily Worker and the Daily World at the Tamiment Library.[15]

In the above photograph, four women sit together at a meeting for the National Welfare Rights Organization in Nevada. The caption below the photograph reads,

LAS VEGAS, Nev.: Several hundred Las Vegas citizens, whipped into an emotional frenzy by representatives of the National Welfare Rights Organization over recent action by Nevada in dumping over 300 alleged unqualified welfare cases from the state’s monthly ‘payroll,’ met 3/5, on the University of Nevada, Las Vegas campus for a rally, preceding an announced protest march along the famous ‘Strip’ 3/6. An unidentified woman, (C), wearing a badge imploring: ‘Adequate Income Now,’ is flanked, (L), by an obviously well fed spectator.

Several phrases used here are telling, especially when considered within their respective historical contexts. First, the author of the caption notes that the National Welfare Rights Organization “whipped” Vegas citizens “into an emotional frenzy.” The word frenzy conveys a state of uncontrollable, wild behavior and thus infantilizes the pictured women. In a patriarchal society in which emotion is seen as weakness, the adjective “emotional” serves to devalue the opinions and actions of the welfare rights activists and to deny that welfare is an inherently emotional issue, affecting every aspect of one’s daily life: disproving it as a politics of survival. Would the phrase “emotional frenzy” have been used if those pictured were not women? Further, the author describes one of the women as “obviously well fed.” This not only evokes a long tradition of monitoring and scrutinizing women’s bodies, but also undermines the precarious circumstances of many welfare recipients.

In the years following, gendered, racialized welfare discourse only became more volatile, and welfare rights movements were systematically destroyed. Overemphasizing “welfare fraud” became a significant point of strategy for some campaigning politicians such as Ronald Reagan. Reagan was able to paint welfare as a “black problem,” despite the fact that the majority of welfare recipients are white. In creating a narrative about welfare recipients which drew on slavery-era stereotypes about black women, Ronald Reagan mobilized white supremacy against welfare—a mobilization which aimed to destroy existing and potential solidarity among welfare recipients. White supremacy gave Reagan the power to erode the American welfare state without facing strong white working-class opposition. Many of Reagan’s claims about Linda Taylor were conjecture, but that did not matter. Reagan struck a chord with the “welfare queen” narrative, and what mattered then was not what was actually true, but what people believed to be true.

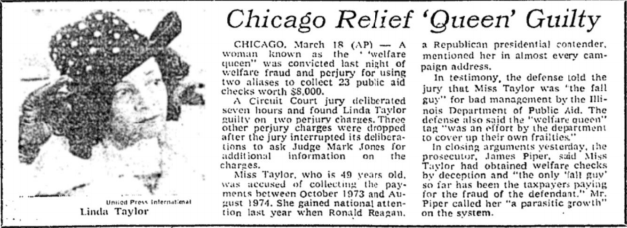

Figure 2. Article from the New York Times, published on 19 March 1997. Found in the TimesMachine archive.

Figure 2. Article from the New York Times, published on 19 March 1997. Found in the TimesMachine archive.

Many New York Times articles from the 1970s publicize Linda Taylor and “welfare fraud,” two of which are titled “Chicago Relief ‘Queen’ Guilty,” and “‘Welfare Queen’ Loses Her Cadillac Limousine.”[16] “Chicago Relief ‘Queen’ Guilty” includes a photograph of Linda Taylor with a lavish hat and gloves (Figure 2).[17] The photograph was taken by a United Press International photographer, which, notably, is the same group that captured the image of the women from the National Welfare Rights Organization in Figure 1. Linda Taylor became not just the face of welfare fraud, but of welfare itself. Taylor was the manifestation of our “unquestioned” consensus about welfare recipients—politicians and media outlets painted her as the reason welfare did not work. During the rise of “welfare fraud” discourse, two contradictory narratives ran parallel: first, the narrative that black mothers did not deserve welfare because they were lazy—they were not even trying to get jobs and second, the narrative that black mothers were strategically and systematically cheating the system, and to expand welfare would only give them more opportunity to do so. With the new narrative of poverty during the 70s and 80s came the turn to neoliberalism and austerity politics, and thus the erosion of the social safety net.

But this is not the whole story. The “welfare mother” identity did not always destroy solidarity—rather, in Las Vegas, it created it. In 1971, Nevada’s government had decided to significantly reduce the reach of its welfare program, with one third of recipients seeing a reduction in benefits and one in three families losing benefits altogether.[18] Welfare mothers in Las Vegas were sick and tired of the contradictory expectations of government officials, who wanted these women off of welfare but did not recognize their work as mothers or help them get jobs aside from motherhood. Three welfare mothers, Rosie Seals, Alversa Beals and Ruby Duncan, realized how little they knew about legislation and their rights as welfare recipients, and they thus began advocating to raise consciousness of issues surrounding welfare and accompanying other mothers to local welfare offices. Johnnie Tillmon, a poor mother’s advocate and organizer, verbalizes this shift in awareness: “In the past, most of us had been so ashamed that we were on welfare that we wouldn’t even admit it to another welfare recipient. But as we talked to each other, we forgot about that shame. And as we listened to the horrible treatment and conditions all over the country, we could begin thinking…that maybe it wasn’t us who should be ashamed.”[19] Welfare mothers in Las Vegas began rejecting the shame and stigma of welfare—they took an identity, the “welfare mother,” which had been weaponized against them, and created a movement. The women were up against numerous obstacles: specifically George Miller, who popularized his own version of the “welfare queen” in Nevada by alleging that one-quarter of mothers on welfare in Nevada were cheating the system. Welfare mothers in Las Vegas aimed to turn this rhetoric on its head and demonstrate the failures of the state through “Operation Nevada,” a march Ruby Duncan and other women organized. The women, joined by various civil rights and labor organizers, stormed Caesar’s palace chanting “We Are into Caesars Palace, and We Shall Not Be Moved.”[20] “Operation Nevada” marked the inception of an incredible solidarity movement among women who decided to reclaim an identity which had been imposed upon them. Ruby Duncan and other Westside mothers took power and demanded better treatment. Yes, they were welfare mothers, and they were damn proud of it.

Non-consensual imagery and identities about welfare recipients, however, were not reserved solely for the perceived “welfare queens” of the 1970s, nor were they isolated to any campaign or time period. The gendered, racialized language became slightly more nuanced in the 1990s, focusing on teenage pregnancy and intergenerational dependence, but nonetheless pervaded welfare discourse.[21] In Scandalize My Name, Terrion L. Williamson recalls her adolescent years in Peoria, Illinois, during which “teenage pregnancy” became a hot topic among news publications, parents and schools. In 1994, Journal Star, a major newspaper in Peoria, ran a series called “Unwed Parents.”

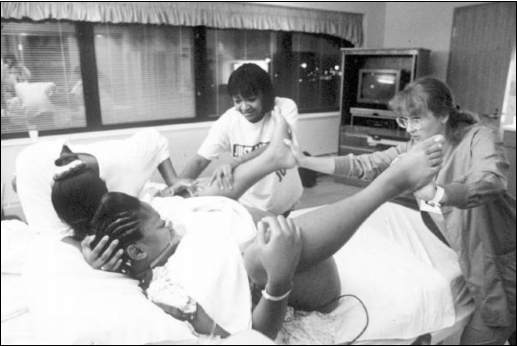

Figure 3. Photographed by Linda Henson for Journal Star, printed in “Unwed Parents” series on 6 February 1994.[22]

Figure 3. Photographed by Linda Henson for Journal Star, printed in “Unwed Parents” series on 6 February 1994.[22]

In this series, photographer Linda Henson captured various images of these so-titled “unwed parents,” most of which were black and female.[23] In one of the more invasive photographs, a sixteen year-old girl is captured giving birth alongside her best friend, who is pregnant for the second time, and her older sister, who is also a mother (Figure 3). In a later photo, these girls are seen signing up together for a municipal public program for baby formula. Debates about the “problem” of teenage pregnancy and what to do about it had plagued the town for years, and although the racialized nature of this debate was not explicitly verbalized, “nothing characterized the underside of the debate better than Journal Star’s dubious attempt at ‘humanizing’ [teenage pregnancy] through its ‘Unwed Parents’ series.”[24] While the photographer and newspaper were indeed humanizing the “unwed parents,” in humanizing teenage pregnancy, they were also stereotyping it. They were imposing an identity politics on the issue. Teenage pregnancy was no longer just “a problem” in Peoria: it was a decidedly black and female problem. Williamson writes,

Inasmuch as the body of a laboring black woman-child became, in Peoria, Illinois, in 1994, the hyper-visual site on which public shame(ing) was both visualized and enacted, that same body is, by historical, cultural, and social extension, a comment on the sexual regulation of black women’s bodies that endures into the contemporary moment.[25]

Journal Star publicized black women’s bodies on its front pages to demonstrate that there was, indeed, a “teenage pregnancy problem” in 90s Peoria. The focus on images of teenage pregnancy, it would seem, was simply rebranding of age-old stereotypes about black women and girls. These young black mothers were “welfare queens” incarnate—a manifestation of poverty as a moral failure as opposed to a structural one. Journal Star’s use of these images was, to the core, a distraction from the structural and institutional forces that keep black women in poverty, as well as under watch of the public eye. In the 1990s, as debates about welfare walked onto the national stage once again, Bill Clinton promised to “end welfare as we know it.”[26] The 90s saw the end of AFDC and the creation of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), which gave states significant control over federal aid and limited the assistance to five years per recipient. Additionally, and crucially, teenage mothers were denied access to TANF.[27]

Why are false narratives about poverty like the “welfare queen” created and perpetuated? Simply put, the “welfare queen,” as other false narratives spanning two centuries, manifested out of a desire to keep capitalism alive. The “welfare queen” was not an isolated incident: it was embedded within a history of the patriarchal and racist control of black and female bodies and the capitalist devaluation of reproductive labor, as well as the vast and ever-present conception of poverty as a moral failing. Capitalism would not have survived without free reproductive labor, without the plunder and exploitation of bodies, and without a perception of poverty that blamed poor people for their own existence. In our current moment, as rollbacks of social services like welfare become more and more threatening, our imaginaries become increasingly limited. It has become more difficult for us to imagine a comprehensive welfare state in America—one with free education, accessible healthcare, guaranteed jobs and income for all, and funded by redistributive and progressive taxation—let alone a society free from oppression and inequality.

Linda Taylor, the original “welfare queen,” rejected a system she found inadequate and took action to work around it. In this way, she is not wholly dissimilar from the Las Vegas welfare rights activists. The concept that a Linda Taylor could even exist is radical: she is a black woman who took more than what she was given, more than what society had determined her to deserve. Our willingness to accept, criticize, and blame the “welfare queen” narrative is indeed founded in various systems of oppression—but perhaps it is also born out of our own narrow conception of what we deserve from the government, the state, society, and each other. The idea that a person, let alone a black woman, could so blatantly reject what many of us so readily accept challenges our own imaginaries. The prevalence of the “welfare queen” image dares us to consider what poverty actually means and how it is created.

Under the broader framework of capitalism, poverty necessarily exists. When we choose to accept this, the question then becomes about who in our society will be poor and how the system will work to keep people in poverty. Under the framework of American capitalism, a large part of the answer to this question lies in the history of institutional racism and sexism. But outside of a capitalist framework, poverty no longer has to appear inevitable.

***

[1] Slate Voice, “Ronald Reagan Campaign Speech, January 1976,” Soundcloud, 2014,

https://soundcloud.com/slate-articles/ronald-reagan-campaign-speech.

[2] Michael B. Katz, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse: A Social History of Welfare in America, 10th anniv. ed. (New York: Basic Books, 1996).

[3] Lisa Levenstein, A Movement Without Marches: African American Women and the Politics of Poverty in Postwar Philadelphia, (North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

[4] Ange-Marie Hancock, The Politics of Disgust: the Public Identity of the Welfare Queen (New York: NYU Press, 2004), 3.

[5] Gunja SenGupta, “From Slavery to Poverty: The Racial Origins of Welfare in New York, 1840-1918 (New York: New York University Press, 2009).

[6] Levenstein, “A Movement Without Marches”.

[7] Anna Marie Smith, Welfare Reform and Sexual Regulation, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

[8] Katz, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse, 132-134.

[9] Katz, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse, 132-134.

[10] Smith, Welfare Reform and Sexual Regulation, 8.

[11] Selma James, Sex, Race and Class—The Perspective of Winning: A Section of Writings 1952-2011 (Oakland, Calif.: PM Press, 2012).

[12] Katz, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse, 132-134.

[13] Levenstein, A Movement Without Marches, 179.

[14] Vivyan Campbell Adair, From Good Ma to Welfare Queen: A Genealogy of the Poor Woman in American

Literature, Photography and Culture, (New York: Garland Publishing, 2000).

[15] Photograph, 5 March 1971, Box 579, Folder 23644 “National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO) – Prints,” “The Daily Worker and the Daily World” Collection, Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Archives.

[16] “Welfare Queen’ Loses Her Cadillac Limousine,”, New York Times, Feb 29, 1976, in the TimesMachine, accessed April 28, 2018,

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1976/02/29/75221493.html?action=click&contentCollection=Arch

ives&module=LedeAsset®ion=ArchiveBody&pgtype=article&pageNumber=42.”

[17] “Chicago Relief ‘Queen’ Guilty,” New York Times, March 19, 1997, in the TimesMachine, accessed April 28, 2018, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1977/03/19/80214466.html?action=click&contentCollection=Arch

ives&module=LedeAsset®ion=ArchiveBody&pgtype=article&pageNumber=8.

[18] Annelise Orleck, Storming Caesars Palace: How Black Mothers Fought Their Own War on Poverty (Boston:Beacon Press, 2005), 1.

[19] Orleck, Storming Caesars Palace, 112.

[20] Orleck, Storming Caesars Palace, 157.

[21] Alma J. Carten, Reflections on the American Social Welfare State: the Collected Papers of James R. Dumpson, PhD, 1930-1990, (Washington, DC: National Association of Social Workers Press: 2015).

[22] Linda Henson, Journal Star, reprinted by Terrion L. Williamson, Scandalize My Name: Black Feminist Practice

and the Making of Black Social Life, (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017).

[23] Henson, Journal Star, reprinted by Terrion L. Williamson, Scandalize My Name.

[24] Williamson, Scandalize My Name, 94.

[25] Williamson, Scandalize My Name, 95.

[26] Katz, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse.

[27] Katz, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse.