by John Leake

On May 1, 1930 the main line of the Turkestan-Siberian Railroad, or Turksib, opened in the Kazakh Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic after almost four years of a projected five-year construction. A part of the Soviet Union’s First Five-Year Plan, the railroad was built to connect Central Asia to Siberia and its neighboring countries. Other industrial projects were being implemented concurrently with the construction of Turksib from 1927-1933, specifically the Dnepr Dam in Southeastern Ukraine and the Magnitogorsk steel plant near the Ural Mountains. Diverse visual representations of the Turksib and Magnitogorsk projects were disseminated to the public by government officials through various media including film, pamphlets and photographs. The visual representations of Turksib and Magnitogorsk differ greatly in their portrayals of their subjects in terms of human characteristics, rhetoric and style. Upon the conclusion of Turksib’s construction, a government pamphlet distributed to French, German and English audiences read that the railroad’s construction, “hums where formerly long caravans crossed the desert lands.”[1] This colonialist tone did not appear in the representations of Magnitogorsk. Yet despite these industrial projects’ differences in visual representation, the ideological goal of crafting model citizens who subscribe to socialist rhetoric and shed their old methods of thinking and practice, were the same. The visual representations of Turksib relate heavily to the idea of Asia in the Russian cultural and political imagination as well as in historiographical debates surrounding Russia’s relationship to Asia during the Russian Empire, the early Soviet period and during the construction of Turksib itself.

Turksib’s construction began in December 1926 with the goal of connecting the railway to the Trans-Siberian Railroad in order to easily facilitate the trade, production and growth of crops such as cotton and grain across Central Asia, Siberia and parts of Mongolia and Western China. The initial length of Turksib, prior to the addition of new lines, amounted to roughly 1,400 kilometers (870 miles) in length running from Seminpalatnisk, Kazakhstan to Frunze (now Bishkek), Kyrgyzstan.[2] Engineers employed by the Soviet government hired roughly 50,000 local Kazakhs to construct the railroad. Turksib’s construction developed within the context of the Soviet Cultural Revolution.[3] Traditionally, the Cultural Revolution was viewed as the State’s attempt to control the cultural institutions of Russia in an effort to create a uniquely Soviet culture. Historians have argued that the ideology of the Cultural Revolution can be applied to Soviet intervention in Central Asia in the 1920s by using the rhetoric of the “backwards nation” or “civilizing mission” in regards to building a multi-ethnic state and incorporating Central Asians into the Soviet proletariat.[4] This rhetoric of ‘civilizing’ reflects ideas of Asia in Russian ideologies that traditionally only focused on changing culture within Russia. Another ideology that developed around this time was Eurasianism, which promoted the unification of all the peoples of Eurasia. [5] Racial tensions emerged during the construction of Turksib between Kazakhs and the Bolshevik engineers, the latter struggled with the former’s proposed integration into the proletariat. There was a desire to oppose the nativization of the Kazakhs and hope that the Soviet Union would recolonize the Kazakh Steppe deeming it backwards and uncivilized.[6] This example of prejudice towards Kazakh workers ties into debates surrounding Russian Orientalism.

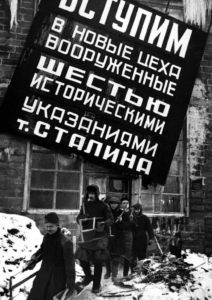

The construction of Magnitogorsk began in 1929 with the goal of “building socialism” in urban areas. As part of the first Five-Year Plan, the project would ideally “catch up and overtake” the West in industrial capacity and demonstrate to the international community the benefits of a socialist system over a capitalist one and usher Russia into the rank of first rate nations.[7] Iron and steel had become a symbol of the the Soviet Union’s potential for industrial might. The plans for the steel plant were modeled after a prominent steel plant in Gary, Indiana.[8] The endeavor of Magnitogorsk itself was two-fold. One portion involved the construction and operation of a steel plant. The Bolsheviks believed that industrialization would transform society.[9] Industrialization would bring the class war between capitalists and socialists to fruition and the act of setting production quotas to achieve industrial goals would help the economy. The other portion of the project revolved around building a “socialist city” in Magnitogorsk as a way of developing “socialist” people who would become indoctrinated into the ideologies of a socialist society. The idea of a socialist city proved to be one of the hardest to realize because it was intangible unlike the prospect of fulfilling specific quotas. The visual representations of Magnitogorsk and Turksib offer insight into the goals of Bolshevism. They also display conceptions of Asia in the Russian imagination, indicated by the details chosen to be included and excluded from the pertinent media.

Portrayals of Turksib’s construction were circulated immediately after the groundbreaking in 1926. Hired photographers recorded the construction process and a feature-length film was produced in 1929 in order to enlighten Kazakh audiences as to how the railway had changed their society for the better.[10] The visual representations of Turksib generally displayed hardworking Kazakhs in a desert landscape with joyous expressions. One photograph depicts a group of Kazakh and Russian workers in the beginning months of construction (Figure 1.1).

The workers are in awe of the magnitude of the project. Their satisfied expressions imply that Turksib will bring about the modernization of Kazakh society and improve their daily lives. The camera angle makes the photograph have a majestic quality because the viewer must infer what the workers are looking at in the distance. The photograph provides a mechanism for portraying Turksib’s potential as a truly modernizing project for the Kazakh people. Another photograph shows Kazakh women on camels in traditional dress presumably watching the construction unfold (Figure 1.2).

Based on their facial expressions, the women seem to be opposed to the idea of the construction and by taking photographs of the native population, Russian audiences were supposed to witness how the railroad would modernize Kazakhs into the integrated proletariat. More concrete evidence of the civilizing mission is provided in the pamphlet produced by VOKS that detailed the progress made during construction. A Russian engineer assigned to the project, N. Bulgakov, stated that one of the significances of Turksib was not only to induct Kazakh workers into the proletariat, but to educate the children of the newly minted proletariat through establishing boarding schools, kindergartens, technical schools and building gymnasiums, auditoriums, and libraries which were lacking in the area.[11] Although these plans were not fully realized, the fact that an entire socialist education system was supposed to be implemented in Turksib points to the civilizing mission and the idea that Central Asia was a backwards region in the minds of Russians. Overall, the representations of Turksib displayed the civilizing mission and implicit racist attitudes that Russians harbored against Central Asians.

Despite analyzing these representations and coming to the conclusion that they are different because Turksib focuses on race, while Magnitogorsk does not, there is room for nuance and, perhaps, a reworking of what could be considered an obvious conclusion. The idea of the civilizing mission is more complex than what is taken at face value. Although it is clear that there was rhetoric of the civilizing mission during Turksib in order to mold Kazakhs into the proletariat and, subsequently, model Soviet citizens, Magnitogorsk implicitly used the rhetoric of developing new Soviet citizens through industrialization tactics. Living in a “socialist city” and becoming a believer in socialist ideologies was a way to become a new, model citizen in Magnitogorsk. In 1936, after the construction of the Magnitogorsk steel plant had been completed, the Stakhanovite movement based on Soviet miner, Alexey Stakhanov, emerged as a result of Stakhanovite over fulfilling his production quota. He subsequently received bolstered benefits from the government, specifically a new apartment.[12] The propaganda that ensued became known as the Stakhanovite movement, which was designed to increase morale, worker productivity, and send a message to capitalist societies that socialism was superior. The key message for the population was that if one worked just as hard as Stakhanov, they too could reap the benefits of the socialist system. Yet, Stakhanov also represents the ideal Soviet worker or citizen that the government envisioned. The goal for all workers to be like Stakhanov and demonstrate that socialism was superior to capitalism. Here, there is the idea that industrialization will make the Soviet Union not only stronger, but indoctrinate people into the socialist rhetoric and see a communist society come to fruition. Just as one of Turksib’s engineers focused on education for Kazakh workers and their children, the engineers of Magnitogorsk also stressed education for the largely illiterate Russian workers in the Magnitogorsk steel plants. John Scott writes in his memoir that “the absence of unemployment and the consequent assurance of being able without difficulty to get a job in any profession learned, supplemented and stimulated the intellectual curiosity of the people” through night classes in which workers were taught how to read and write or, if literate, classes on technical skills or other topics.[13] In other words, it appears that both Turksib and Magnitogorsk were intent on creating new, ideal Soviet citizens by civilizing them into a socialist doctrine and modernizing them into a socialist society based on a highly industrialized planned economy. Although race does play a factor in the representations of the projects, the overarching goals of civilizing and modernizing are the same. Perhaps, this plays into the idea that socialist rhetoric is universal, but it also relates to how ideas of empire and civilization are explored in scholarship and are not clearly defined and need to be defined more acutely.

The early Soviet period saw the emergence of the Soviet Empire in the Baltic region, the Caucasus, and Central Asia, which would ultimately become socialist republics of the Soviet Union. It is important to note that most of the territories that became a part of the USSR were originally a part of the Russian Empire. From the mid-1920s through the mid-1930s, Soviet officials went into Central Asia in order to civilize what they presumed were backwards countries in order to make them modern. In a process called Nativization (“korenizatsiia”), Soviet officials attempted to select certain indigenous peoples for leadership positions in political, economic and cultural institutions, and the use of native languages over Russian in an attempt to make Central Asian members of the proletariat and for the party to refute the imperialist belief of the Tsarist government that Central Asia was forever backwards. Through modernizing Central Asia the Soviets could prove that the region was capable of shedding its traditionalist (primarily Muslim) ways.[16] In terms of these government goals impact on culture, examples from film display the ways in which the Soviet government displayed these civilizing missions to both Russian and Central Asian audiences. One example is from 1929 in Tashkent, Uzbekistan in which the main message from the film is that new houses for Uzbek proletariat workers were destroying the old ways of life in the predominantly Muslim city. The clip juxtaposes images of dirt houses presumably lived in by native Uzbeks, with new buildings inhabited by the Uzbek proletariat and Russians as the screen reads, “In the new houses, lives the new people.”[17] Another example is the All-Union Conference of the Wives of Red Army Commanders’ attempt to remove the traditional veils of Turkmen women in order to put on gas masks. The clip depicts Russian women demonstrating to a crown of Turkmen women how to properly put on a gas mask, as it is a symbol of modernity and will protect them during an emergency situation.[18] Both these visual depictions of the nativization in Central Asia provide insight into how the process was viewed and thought of by propagandists and that the idea of old versus new fit into the civilizing mission, but also the mission of the entire Soviet project, both internally in Soviet Russia and externally as well.

The encouragement of the use of native languages over Russian is intriguing because it calls into question the idea of empire and cultural conquest in Central Asia. By encouraging the use of local languages, the Soviet government was encouraging that indigenous peoples preserve their linguistic culture, so long as they would become a part of the proletariat. It raises the question: to what extent was the Soviet intervention a conquest? Adeeb Khalid argues that Soviet intervention in Central Asia was not similar to the modes of conquering done by a traditional empire, writing that “early Soviet Central Asia cannot be understood as a case of colonialism” due to the Soviet desire to create “the activist, interventionist, mobilizational state that seeks to sculpt its citizenry in an ideal image.”[19]

Khalid further argues that traditional empires perpetuate difference by keeping a distance between the colonizers and the colonized and proposing that the colonized could one day become a part of a “universal civilization.“ In contrast, Soviet intervention in Central Asia was based on the conquest of difference in that the Soviets sought to transform Central Asians into ideal Soviet citizens and proletarian members. By shedding the old ways of life and ushering in the new ways, the Soviets attempted to conquer differences that existed between the multi-ethnic peoples of the country and form a Soviet citizen in whom racial differences did not matter over socialist ideology. This utopian goal for Central Asia reflects how ideas of Asia during the early Soviet period shifted from a myriad of debates on Russia’s relationship to Asia to a socialist ideology of a less racialized society spearheaded by the Communist Party..

The construction of the Turkestan-Siberian Railroad ushered in a new wave of modernization and technology in Central Asia, specifically Kazakhstan, under the direction of Soviet Russia. In a similar vein, the construction of the Magnitogorsk steel plant and city of the same name ushered in a new industrialized spirit to Soviet Russia that had never been experience before. The visual representations of Turksib and Magnitogorsk differ drastically in their style and approach. The visual representations of Turksib promote a civilizing mission in which the railroad would bring modernity to a backwards and barbaric country. In contrast, the visual representations of Magnitogorsk focus solely on the modernization of Russia and make no reference to race or ethnicity. However, despite differing visual representations, the ideological goals of the project are the same in that they both strived to create model, Soviet citizens through education and labor that adhered to socialist ideologies. This raises the question as to how terms such as “empire”, “modernization”, “conquest” and “civilizing mission” are defined in scholarship and if these terms need to be more clearly defined. Depictions of Turksib contribute to conceptions of Asia in the Russian context during the Russian Empire and early Soviet period. The representation of infrastructure projects provide insight into Russian views on race and ethnicity as it relates to their relations with Asia and the precarious balancing act of an “antiquated” mindset with socialist ideology.

***

[i] Shaiket, Arkady, S., Photographer. “Kazakhi- stroilteli Turksiba. Na puske Turksiba.” Photograph. Moscow: 28 April 1930. From Multimedia Art Museum and Moscow House of Photography: Istoriia Rossii v fotografiiakh. https://russiainphoto.ru. (Accessed 28 September 2016).

[ii] Source: Shaiket, Arkady, S., Photographer. “Na smychku turksiba. Turkmenkina verbliuge.” Photograph. Moscow: No publisher. 1930. From Multimedia Art Museum and Moscow House of Photography: Istoriia Rossii v fotografiiakh. https://russiainphoto.ru. (Accessed 4 November 2016).

[iii] Source: Unknown, Photographer. “Magnitostroĭ.” Photograph. Chelyabinsk: No publisher. circa 1933. From The State Historical Museum of the Southern Urals: Istoriia Rossiiv fotografiiakh. . https://russiainphoto.ru. (Accessed 27 November 2016).

[iv] Source: Unknown, Photographer. “Mahnitogorskii <gigant>> i stroitel’.” Photograph. Chelyabinsk: No publisher. circa 1930. From The State Historical Museum of the Southern Urals: Istoriia Rossii v fotografiiakh. https://russiainphoto.ru. (Accessed 27 November 2016).

[1] Vsesoîuznue obshchestvo kul’turnoi svîazi s zagranitsei. Turksib; on the opening of the Turkestan-Siberian railway, (Moscow: Soviet Union, May 1st 1930) 1. The weekly pamphlet provided updates on the scientific, technological and artistic progress made in the Soviet Union.

[2] Matthew J. Payne, Stalin’s Railroad: Turksib and the Building of Socialism (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2001), 36.

[3] For the genesis of scholarship on the Soviet Cultural Revolution see Sheila Fitzpatrick, Cultural Revolution in Russia, 1928-1931 (Bloomington, IN, 1978).

[4] Michael David Fox, What Is the Cultural Revolution?: Key Concepts and the Arc of Soviet Cultural Transformation, 1910-1930s, in Crossing Borders: Modernity, Ideology and Culture in Russia and the Soviet Union (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 2015), 118-119.

[5] For more of the historical roots of Eurasianism, see Mark Basin, Gumilev Mystique: Biopolitics, Eurasianism and the Construction of Community in Modern Russia (Ithaca, NY, 2016), 82-85; For more on modern Eurasianism in Russia, see Alexander Dugin, Eurasian Mission: An Introduction to Neo-Eurasianism (London: Arktos Media Ltd, 2014).

[6] Matthew J. Payne, Stalin’s Railroad: Turksib and the Building of Socialism (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2001), 10, 92.

[7] Stephen Kotkin, Magnetic Mountain: Stalinism as a Civilization (Oakland: University of California Press, 1997, revised edition), 42.

[8] John Scott, “Introduction” in Behind the Urals: An American Worker in Russia’s City of Steel, ed. Stephen Kotkin (Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1989), xviii. This memoir provides a first hand account of an American living in Magnitogorsk during its construction.

[9] Stephen Kotkin, Magnetic Mountain: Stalinism as a Civilization (Oakland: University of California Press, 1997, revised edition), 33.

[10] Turksib, directed by Viktor Turin (Turkmenistan, USSR: Vostokkino, 1929).

[11] Vsesoîuznue obshchestvo kul’turnoi svîazi s zagranitsei (Soviet Union), 25-26.

[12] Seventeen Moments in Soviet History, “Happy Housewarming, Comrade Busygin!” Russian State Film & Photo Archives at Krasnogorsk, January 2000, http://soviethistory.msu.edu.

[13] John Scott. Behind the Urals: An American Worker in Russia’s City of Steel, (Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1989), 49.

[14] Nathaniel Knight, “Grigor’ev in Orenburg, 1851- 1862: Russian Orientalism in the Service of Empire?,” Slavic Review 59, no. 1 (2000): 98.

[15] Adeeb Khalid, “Russian History and the Debate over Orientalism,” Kritika: Explorations in Russia and Eurasian History 1, no. 4 (2000): 697. This article was written partly in response to the article footnoted above. For more on the historiography of Russian Orientalism from Peter the Great to February Revolution of 1917, as well as an analysis of varying schools of thought on Asia within the imperial period, see David Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, Russian Orientalism: Asia in the Russian Mind from Peter the Great to the Emigration (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010), 8-11, Chapters 5 and 7. Also see, Kalpana Sahni, Crucifying the Orient: Russian Orientalism and the Colonization of the Caucasus and Central Asia (Bangkok: White Orchard Press, 1997).

[16] Yuri Slezkine, “The USSR as a Communal Apartment, or How a Socialist State Promoted Ethnic Particularism,” Slavic Review 53, no. 2 (1994), 419.

[17] Seventeen Moments in Soviet History, “Destroying the Old Life (1929).” Russian State Film & Photo Archives at Krasnogorsk, January 2000, http://soviethistory.msu.edu. The website is an online archive of primary source material.

[18] Ibid. , “Red Army Wives in Turkmenistan (1936)”

[19] Adeeb Khalid, “Backwardness and the Quest for Civilization: Early Soviet Central Asia in Comparative Perspective,” Slavic Review 65, no. 2 (2006), 232-233.

[20] Katherine Holt, “The Rise of Insider Iconography: Visions of Soviet Turkmenia is Russia- Language and Film, 1921- 1935” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2013) ProQuest (AAT 3595797), 90-91.