by Grace Rogers

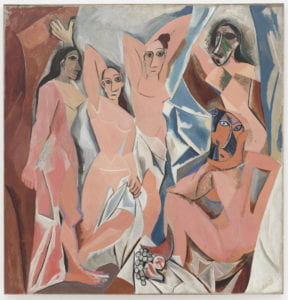

In the early 20th century, a new epoch of Western-dominated globalism took flight: the French colonial project began its “civilizing mission” in West Africa, the British linked their massive empire through telegraph cables, and Joseph Conrad published Heart of Darkness. African objects were brought back to Europe and placed in ethnological museums, giving Europeans visual representations of the far-off communities they read about in the papers. And around 1905, amidst swirling tales of cannibalism and exoticism, Pablo Picasso acquired one of these objects — a West African mask. He had little interest in the mask’s origins but admired its planes and cylinders, and quickly filled his studio with more objects from anonymously “exotic” people and places. There he would paint Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), credited as the seminal work of modernism, particularly within a trend that suddenly recognized “tribal” objects as powerful “art” in the early twentieth-century.

By the mid-1980s, the trend had fully taken shape — one could encounter tribal objects in an unusual number of noteworthy locations in New York City. This paper will focus on the period’s most prominent and perhaps most controversial exhibit, “‘Primitivism’ in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern,” which sought to explore tribal culture’s influence on modern art through an aesthetic perspective. Displayed at the Museum of Modern Art in 1984, the exhibit raises questions about how the modern art period “othered” non-Western culture, particularly via the art institution. This paper argues that the MoMA’s attempt to contextualize tribal culture within modern art depended on an assumed Western superiority in tastemaking: in deciding what to consider “art” globally. By only focusing on the aesthetic, the exhibit relied on a violent erasure of history that locked tribal culture into antiquity, serving primarily to inform a modern Western status.

“‘Primitivism’” was curated by William Rubin, the director of painting and sculpture at the MoMA from 1973-1988. It included modern art by Picasso, Max Ernst, Paul Klee, Henri Matisse, Paul Gauguin, Georges Braque, Alberto Giacometti, the Dadaists, Surrealists, the Fauves, and others; tribal works came from the Zunis in New Mexico, the Eskimos of the Northwest, the Dogon, Baule/Yuro/Guro, Dan, Yoruba, Fang, Kota, Kongo/Vili/Wogo, and other peoples of Africa and Oceania, especially those of what is now Indonesia and New Guinea.[1] Notable from the exhibit’s massive two-volume catalogue, the show was part of a wider revival of interest in “primitive” objects within modern art, marked by similar occurrences at the Israel Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Brooklyn Museum, the Ackland Museum (Chapel Hill, N.C.) and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, M.O.). But before that interest can be seen for what it is — a Western-oriented intrigue that excludes other histories — the term “primitive” must be defined.

To study to primitive is thus to enter an exotic world which is also a familiar world. That world is structured by sets of images and ideas that have slipped from their original metaphoric status to control perceptions of primitives — images and ideas that I call tropes….The ensemble of these tropes — however miscellaneous and contradictory — forms the basic grammar and vocabulary of what I call primitivist discourse, a discourse fundamental to the Western sense of self and Other .[3]

In describing the primitive from a Western perspective, the distinction between abstract metaphor and concrete perception becomes slippery, as each impacts the other to create primitivist discourse. In this discourse, images and ideas not only form how we describe the Other, but additionally, how we posit a standard opinion on the Other. It can further be likened to what Said refers to as the “exteriority” intrinsic to Orientalism, which includes the various styles, figures of speech, narrative devices, settings, and historical and social circumstances of or employed by the West.[4] Exteriority is not the truth about the Orient, but a representation — culture is the powerful infrastructure that articulates representation as truth. Indeed, the “‘Primitivism’” show is an apt example of the continued material investment that made Orientalism, as a system of knowledge about the Orient, an accepted grid for filtering into Western consciousness. Within the arts in particular, exteriority becomes complicated: art institutions in the West have modified its relationship to the primitive countless times, through seemingly small but nonetheless consequential aspects such as wall labels, layout design, and catalogue language. In 1984, the MoMA was undergoing such a modification, as it believed their newfound appreciation for tribal art was, culturally, a step in the right direction.

In the exhibit catalogue, Rubin defines primitivism as “the interest of modern artists in tribal art and culture, as revealed in their thought and work” [5]. He explicitly notes it is an ethnocentric term, but that the MoMA’s usage is “never pejorative” precisely because it is an “art term” [6]. He places blame on the public of the nineteenth-century for using such terms pejoratively, casting such attitudes as complete and in the past because the West now considers their objects “artful.” Indeed, the brochure available to each visitor at “‘Primitivism’” encapsulates how most modern artists viewed the tribal cultures they were taking from. It states:

The term “primitivism” does not refer to tribal art itself, but only to modern Western interest in it. Our exhibition thus focuses not on the origins and intrinsic meanings of tribal objects themselves, but on the ways these objects were understood and appreciated by modern artists. The artists who first recognized the power of tribal art generally did not know its sources or purposes. They sensed meanings through intuitive response to the objects, often with a “creative misunderstanding” of their forms and functions.[7]

This quotation shows that omission of political and ethnographic concerns from the exhibit were deliberate. Clearly, the writers of this statement recognized and sidestepped the political problems inherent in the show, yet these disclaimers do not vindicate the exhibitors. In fact, these deliberate omissions raise new concerns that are based in a centuries-old, Orientalist ideology. The MoMA’s framing of tribal objects in “‘Primitivism’” had three main consequences: it (a) sought innocence through aestheticization, (b) assumed a Western superiority of taste and ability, and (c) locked non-Western cultures in a vague past, conceiving them as an abstract symbol of mankind. The latter half of this paper is dedicated to discussing these three effects.

“‘Primitivism’” read tribal culture through an explicitly aesthetic lense and therefore disregarded the objects’ historical context, cultural significance, and locality. The modern artists featured at the exhibit lacked knowledge of what these objects meant, who made them, and where they were made, and the exhibit itself expressed no desire for such context. Indeed, the catalogue states that Picasso “usually did not even distinguish between African and Oceanic art,” and instead used tribal sculpture as “an elective affinity and secondarily a substance to be cannibalized”[8]. Rubin comments on a Pende mask by describing its linear abstraction and precise edges, and contrasts the convexity of the forehead with the concave areas of its bottom[9]. His description is completely void of meaning and context, though it is fairly assumed Rubin knows that all African masks were parts of costumes and dances. This example highlights the attitude central to the belief that the West’s newfound ability to artistically appreciate tribal objects allowed them to ignore the contexts and consequences of their actions. As historian James Clifford states in his book, The Predicament of Culture, an ignorance of cultural context seems almost a precondition for artistic appreciation[10]. The object is detached from its history in order to circulate it freely in another — in a world of modern art, museums, and markets. For the United States in particular, this feeds into the liberal consensus that “true” knowledge must be non-political, just like how the primitive speaks to an essential human nature. Said states:

Nevertheless the determining impingement on most knowledge produced in the contemporary West (and here I speak mainly about the United States) is that it be nonpolitical….Once can have no quarrel with such an ambition in theory, perhaps, but in practice the reality is much more problematic. No one has ever devised a method for detaching the scholar from the circumstances of life, from the fact of his involvement (conscious or unconscious) with a class, a set of beliefs, a social position, or from the mere activity of being a member of a society.[11]

This pertains to the American artist or art curator studying the primitive, in that he cannot detach himself from his own Western hegemony that — by very nature of its Orientalist framework — is far from the “truth.” Thus, even artistic appreciation (or, to use the exhibit’s phrasing, “affinity”) of the primitive cannot be done neutrally as a Euro-American, even if boiled down to an aesthetic conversation. Importantly, this aestheticization of tribal objects requires an artistic assessment, which is controlled by the West — not only at the MoMA, but globally.

The MoMA not only heralded tribal objects as aesthetically beautiful works, but it also gave credit to Western “voyagers, colonials, and ethnologists” for “discovering” the objects and to modern artists for turning them into art[12]. Similar to the West’s conception of Tutankhamun (“King Tut”)’s treasures, which were found by English archaeologist Howard Carter in 1922, the tribal objects displayed at the MoMA were posited as art that — because of modern artists — were “elevated” from the status of artifact. Further, Rubin described the entire continent of Africa as a society that falls short of having gifted artists and a concept of Fine Arts in the exhibit’s catalogue[13]. Rubin’s framing perpetuates an Orientalist image of a tasteless, uncultured primitive and relies on a concept Melani McAlister calls “imperial stewardship.” The logic of imperial stewardship depends on combining universalist rhetoric with a presumption of American and Western superiority so profound it remains unspoken [14]. Imperial stewardship within a Western art institution like the MoMA creates the image of the Western curator as the “rescuer” that turns non-Western objects into art. Rubin frames this logic as a virtue to be celebrated:

We experience the entire history of past art in varying degrees fragmentarily and largely shorn of context….This ethnocentrism is a function nevertheless of one of modernism’s greatest virtues: its unique approbation of the arts of other cultures. Ours is the only society that has prized a whole spectrum of arts of distant and alien cultures. Its consequent appropriation of these arts has invested modernism with a particular vitality that is a product of cultural cross-fertilization.[15]

Due to lack of context, nothing in the MoMA’s exhibit suggested that good tribal art was being made in the 1980s. The tribal objects on display lacked any position within history, as they were primarily located in a purely conceptual space defined by “primitive” qualities (Rubin cites magic, ritualism, closeness to nature, and mythic or cosmological aims)[17]. Indeed, the exhibit paid fetishistic attention to the dating of Western objects, but the tribal objects were merely labeled by centuries[18]. This is painfully reminiscent of the label “nineteenth-twentieth century” that accompanied African and Oceanic pieces in the Metropolitan Museum’s Rockefeller Wing at the time[19]. Reflective of how Western scholarship formulated the primitive, Western art institutions like the MoMA portrayed tribal culture as timeless and ahistorical, abstracting every detail to the point wherein tribal objects became symbols of humanity’s origins under a sort of “art universalism.” Art universalism rests in the belief that certain art has the ability to completely transcend cultural and historical contexts and therefore cannot be “owned” by any one nation or any group of people[20]. Much of the language that accompanied “‘Primitivism’” described modern artists finding a universal “truth” in tribal works that ultimately led to a self-analysis of the artist’s own origins. As Rubin states:

Yet there is a link, for what Picasso recognized in those sculptures was ultimately a part of himself, his own psyche, and therefore a witness to the humanity he shared with their carvers….If the otherness of the tribal images can broaden our humanity, it is because we have learned to recognize the otherness in ourselves .[21]

It is precisely because Picasso and the MoMA are dominant influencers within a Western hegemony that claims rightful ownership of mankind’s objects, citing a superior knowledge of the shared humanity they represent. Said’s Orientalism makes a direct connection between knowledge, power, and authority that explains the contradictory nature of Western “ownership” of a common heritage of mankind:

Knowledge means rising above immediacy, beyond self, into the foreign and distant. The object of such knowledge is inherently vulnerable to scrutiny; this object is a “fact” which, if it develops, changes, or otherwise transforms itself in the way that civilizations frequently do, nevertheless is fundamentally, even ontologically stable. To have such knowledge of such a thing is to dominate it, to have authority over it. And authority here means for “us” to deny autonomy to “it” — the Oriental country — since we know it and it exists, in a sense, as we know it.[22]

Knowledge, in this sense, becomes a Western-dominated stance that claims to best understand the “foreign and distant” while disregarding any alternative from the cultures in question. It is a deterministic act that, by creating knowledge of the Other, denies the Other power to construct its own narrative. Art universalist rhetoric, then, is employed by Western art institutions like the MoMA as an assertion of knowledge and, thus, an assertion of power. By claiming to know tribal culture better than anyone who has the capacity to appreciate art, Western art institutions grant themselves the authority to imply that noteworthy tribal art (and, even further, tribal people) do not currently exist. This results in distorted, inaccurate representations of groups of people within entire continents that — because of a certain power position — is absorbed as truth.

***

[i] Installation View of “Primitivism in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern.” September 19, 1984–January 15, 1985. Photographic Archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. IN1382.54. Photograph by Katherine Keller

[1] Marianna Torgovnick, Gone Primitive: Savage Intellect, Modern Lives (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 120.

[2] Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books, 1978), 3.

[3] Torgovnick, Gone Primitive, 8.

[4] Said, Orientalism, 21.

[5] William Rubin, “Introduction” in “Primitivism in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern, vol. 2 (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1984), 1.

[6] Rubin, “Introduction,” 5.

[7] Rubin, “Introduction,” iv.

[8] Rubin, 14.

[9] Rubin, 60.

[10] James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988), 200.

[11] Said, Orientalism, 10.

[12] Rubin, “Introduction,” 7.

[13] Rubin, 21.

[14] Melani McAlister, “King Tut, Commodity Nationalism, and the Politics of Oil, 1973-1979” in Epic Encounters: Culture, Media, and U.S. Interests in the Middle East Since 1945 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 129.

[15] Rubin, “Introduction,” 41.

[16] Torgovnick, Gone Primitive, 82.

[17] Rubin, “Introduction,” 9.

[18] Torgovnick, Gone Primitive, 121.

[19] Clifford, The Predicament of Culture, 201.

[20] McAlister, “King Tut,” 129.

[21] Rubin, “Introduction,” 73.

[22] Said, Orientalism, 32.