Nonsense

A. n.

I. Senses relating to absence of rationality or meaning

i. a. That which is not sense; absurd or meaningless words or ideas

b. Foolish or extravagant conduct; silliness, misbehavior. Chiefly in negative contexts, as to stand (also take) no nonsense, there is no nonsense about (a person), etc.

c. Used as an exclamation to express disbelief or surprise at a statement

—- The Oxford English Dictionary[1]

November 24, 1986 — Around a circle surrounded by cryptic protestations “Without assassination of art, there can be no peace!”; “Art is like opium!”; and “Dadaism is Dead!”; the Xiamen Dadaists concluded their retrospective exhibition by burning nearly sixty artworks, mostly oil paintings in the public square of the Xiamen Palace Museum.[i] For Huang Yongping, the destruction of his body of work prior to 1986 was a liberating act, one that clarified his desire to break with the past. In his essay “Xiamen Dada-Postmodern?” written shortly after the exhibition, Huang declared that the public burning was to provoke further participation in the “chaos of the national avant-garde.”[2] He targeted not the political system, but rather the discourse of “mainstream avant-garde artistic trends of the time.”[3]

An act such as Huang Yongping’s burning of his works is labelled as “performance art,” yet the content is more complex. Huang declared that he has rebelled against the mainstream; in this aspect, he was not unique because many contemporaries of his time often also made works of art that are considered radical or anti-institution. As Lu Peng comments, “not all the participants subscribed to the spirit of Dada,[4]” but the way in which works were created and intentionally destroyed certainly did have Dadaist overtones. However, Lu Peng notes that Huang’s strategy was “methodical”; Huang aims to trigger many different ideas, provoke our personal connections to history, present, and future. Though inspired by the spirit of anti-materiality of the Western Dadaists, Huang noted in an essay that the term was simply a placeholder for much more complex thoughts and processes of thinking: “…the exhibition was named after Dada with the purpose of using the term Dada at will, without caring whether it fit in with the context or not…”[5]

Interpreting Huang Yongping is an intellectual challenge because his work is guided by many thoughts that are frequently contradictory. His work is closely connected to personal experience, such as responding to a book or an event in the news. To interpret Huang Yongping requires a certain degree the author’s lived experience, which is lacking in this paper. To create a coherent narrative, it is necessary to select certain pieces to not become lost; yet, one must in the words of John Dewey not “lose sight of the forest for the trees.” Specifically, I do not touch on his works of a religious and cultural nature. Instead, I have focused on works that provoke tension in academia and the world stage. He provokes critique of the writing of history as remembered and reported regardless of the veracity of the events. For Huang Yongping, history is about perception that incites argument and exchange. As Huang wrote in his personal notes in 1984 after reading a text by Wittgenstein, he felt a “need to reexamine instinct and unconsciousness.”[6] What Huang proposes is beyond an argument over revisions of history; Huang invites the viewer to think about a hidden authority during recording of every event. This line of thinking has become even more conscious in his recent work, which resonates with patterns of history and anticipates the future. Dadaism for Huang Yongping is not nonsense, but to make sense of the history of civilization.

EDUCATION AND REACTIONS TO PHILOSOPHY

In 1977, Huang Yongping entered the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Art, where he majored in oil painting. In school, he was influenced by peers and their anti-academicism.[7] One source of inspiration for anti-academicism were books that Huang Yongping read at the academy. He noted that the academy enabled students to read various texts but actively discouraged students from following their ideas.[8] Though Western literature had circulated in China in hand-copied manuscripts before the 1980s, it became legal to publish while Huang studied at the academy. According to the artist, original translations were less common because many books were heavily edited.[9] Meanwhile, printed catalogues of collections in overseas art museums were available, but textual explanations were terse and lacked context about the origin of an artwork. Consequently, Huang attempted to understand Western art through pieces of Chinese and Western philosophical texts, which he used to explain the work of art. The writings of artist-philosophers like Duchamp, and Daoist classics provided for him an approach to art. Huang wrote in his notebook between 1980 and 1982 that his spray gun that he used to paint “no longer serves simply to represent the ideas of the painter…a tool here is no longer a simple tool but has changed from the passive to the active…the tool inspires us more than anything else.[10]

Fascination by the medium’s materiality is not an original idea. Clearly, Huang’s early years were spent in study and constant reflection. As his ideas became more coherent, Huang was not very different from his Western counterparts. Due to his own efforts, Huang received a different kind of education from “folk artists,” who learned the “craft” but not “ideas.” Fei Dawei, Chinese art critic and professor at CAFA, writes that Huang Yongping’s “early works often use the method of subverting logical thinking to reveal the internal contradictions of art as a cultural phenomenon…from 1980 to 1989…the scope and scale of the issues involved — was like an exploratory fleet getting ready to pull up anchor and set sail.”[11] Instead of being fixated on the craft, Huang Yongping became aligned to a mode of thinking. That mode of thinking is interpreting a work of art as an event to break free from the practice of art, as he explained in an essay from 1987: “…walking out of the studio and using all kinds of means, with all kinds of purposes or without purpose, to carry out an event…becomes a principal means for those who are resolved to break away from painting or sculpture but want to go on existing with the identity of ‘arts.’”[12]

XIAMEN AS INDUSTRIAL CITY

The late 1970s through mid-1980s was an exciting time to be living in southern China. The immediate effect of relaxing rules in the 1980s was the rise of independent art exhibitions. During this time, Huang Yongping began to question his “nationality” and even cultural identity. Benjamin Anderson proposes in in Imagined Communities that a nation is a “an imagined political community – and imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign.”[13] It is imagined because people of disparate cultures happen to be grouped in one boundary, and limited because that group will always develop a feeling of mistrust for people outside the boundary. As the home to many variations of Buddhist, Daoist, and even Christian teachings or cults, Huang would have observed conflicts over faith. Thierry Raspail, director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Lyon has said that Xiamen was a multidimensional space. Located in southern Fujian province, across the island of Taiwan, and between the Pearl and Yangtze River Delta regions, Xiamen had been a transit city for pilgrims, merchants, scholars, and soldiers. People come to Xiamen, the exit point from China to Southeast Asia, not to stay but to leave. In 1661, Xiamen was the launching point of the military general Koxinga’s expedition to Taiwan to expel the Dutch, the first and only oversea military expedition undertaken by China against a colonial power. In 1683, the Kangxi Emperor reclaimed the island, and opened Xiamen as a port for trade. Qing forces reclaimed the island, and Kangxi opened Xiamen as the only trading port from Taiwan to Southeast Asia.[14] In the mid-19th century, Xiamen witnessed another period of explosive growth when the British secured Singapore as its headquarters in Southeast Asia,[15] and Xiamen dropped its trade restrictions against non-Chinese ships after the First Opium War. An Englishman from 1843 noted at the time that “”[Xiamen] is very extensive, and contains at least two hundred thousand inhabitants. All its streets are narrow, the temples numerous, and a few large houses owned by wealthy merchants…Vessels can sail up close to the houses, load and unload with the greatest facility, have a shelter from all winds, and in entering or leaving the port experience no danger of getting ashore.”[16] Between the isolation period from 1949 to 1971, Xiamen became a staging area for China’s plan to invade Taiwan. Though the plan was abandoned, the city remained on high alert as Taiwanese planes flew overhead and dropped propaganda leaflets. However, Xiamen retained its role as the go-between city; the Gaoji Causeway and Yingxia Railway projects took place in Xiamen during China’s “industrial revolution” in the 1950s.[17] From 1980 onwards, Xiamen became a special economic zone under orders from Deng Xiaoping to reform China’s economy for re-entry to the world.[18] Thus, Xiamen became an “example city” for China’s experiments with economic reform.

For Huang Yongping, Xiamen was the point of departure from China to France in 1989. In Xiamen, Huang observed the influx of enterprises from Taiwan and the West, as well as return of overseas Chinese. In Xiamen, Huang practiced the method of deconstructive thought by identifying parallels between Chinese and Western philosophical texts. While teaching art in a local school, Huang Yongping analyzed Xiamen like a scholar of comparative literature, politics, and culture – a comparative anthropologist. As French critic Donatien Grau comments, Huang became the “propagandist, or popularizer, of a world foreign to the context in which he now lives.”[19] Known as Amoy to outsiders but Xiamen to insiders, Huang aimed to discover the essence of the city that exist somewhere between perception of the city by outsiders and insiders. Huang said that “…my creative path was primarily formed in China, and I have not fundamentally changed…one always adheres to a certain perspective, and at the age of thirty-five my worldview had already been formed, so it was very difficult to change.”[20]

THE THINKING PROCESS

Before the event of November 24, 1986, Huang Yongping wrote the “Statement on Burning.” In this testament, Huang railed against art criticism and the definition of an artist by one’s portfolio.[21] Quoting Duchamp, the sayings of Chan Buddhist monks, Huang criticized the concept of artistic freedom in “Xiamen Dada, Postmodern?”[22] Huang pointed to the self-collapsing nature of “artistic freedom”; if freedom has to be given to the artist, how can one say that the artist is “free?” Huang arrived at one conclusion: the destruction of everything he had done before that moment.

After the event of November 24, 1986, Huang Yongping and his colleagues had difficulty finding a space willing to host their exhibits. During this time, Huang constantly clashed with a constant swing between approval and disapproval by official art venues. The Xiamen Dada submitted a fake proposal to an official gallery space, the Fujian Provincial Art Gallery. Huang intended to create “an event…an exhibition with unlimited boundaries,”[23] and the plan was to bring random objects from around the museum that were not made by artists into the hall. When the show was finished, they would return the objects to their original places. When the staff realized Huang’s mischief, they immediately shut the exhibition. This “event” is revealing of Huang’s state of mind. Huang was infused with many thoughts that his early works were identified by their lack of philosophical or discursive logic. Yet, Huang constantly wrote notes about his thoughts and collected photographs like an archivist. For example, in 1987, Huang and his colleagues “threw” their artworks in a garbage dump. When people came to inspect the thrown-out frames and painted canvas, Huang began taking pictures of the people. When his “audience” realized that they had unintentionally stepped onto Huang’s stage, some became violent and tried to snatch their cameras away from them.[24] Hence, Huang could not easily forget things that he had thought about; for example, Huang admitted that he was drawn to Wittgenstein’s theory because he discovered parallels between his and Wittgenstein’s thoughts.[25] He had felt a kind of exoneration and excitement at independent but relatable developments in Chinese and Western thinking. From his 1984 notes, “Reflections on Wittgenstein,” Huang wrote, “It seemed that my thoughts were rather confused, and in many ways I still could not get away from formalism. The forms we had learned and seen had already penetrated our instinct and unconsciousness. We need to reexamine the so-called instinct and unconsciousness.”[26] Huang copied a few lines from Wittgenstein’s text, including “An action without purpose is not necessarily an instinctual action” and “Most instinctive gestures already penetrated into the realm of meaning and purpose.”[27]Huang’s method is the scientific method; he creates a hypothesis in art, and searches for evidence through writings or historical events to support or invalidate his hypothesis. His works of art should be interpreted like a text. It is revealing to look at Huang’s mind maps, a technique taught to young school children. The brainstorming process is fundamental to human thinking, a process that Huang deconstructs in his artwork.

A HISTORY OF CHINESE AND WESTERN PAINTING

In the mind map of A History of Western and Chinese Art Washed in a Washing Machine for Two Minutes, Huang started with the character xi, which by itself means “to wash,” and grew the character-idea. The idea changes when xi is paired with another character; it can change drastically from an act of washing to “indoctrination” and “purification.”[28] The artwork consisted of washing for two minutes in a washing machine two standard art history textbooks in China in the 1980s, Herbert Read’s A Concise History of Modern Painting and Wang Bomin’s The History of Chinese Painting. The end product is an unrecognizable pulp, which Huang placed on top of a broken piece of glass placed on top of an open wooden box. Why should Huang Yongping take up this subject? From his personal notes, Huang felt that reading philosophical works from East and West allowed him to “subvert logical thinking to reveal internal contradictions of art as a cultural phenomenon.”[29] Like the divergent perceptions of Xiamen/Amoy, Huang encountered two “credible” viewpoints of history. A Chinese artist educated in the academy in the 1980s would have studied the history of art that built up to the greatness of Abstract Expressionism. These categorical eras of art history – Abstract Expressionism, Realism, Expressionism, and “multimedia…conceptualism” did not feel right to Huang Yongping, who thought that postmodern Western philosophy specifically aimed to demolish these categories. [30] Indeed, Huang Yongping’s various run-ins with official art venues in the mid-1980s fed his resentment of the art institution-system, like a scholar who has been rejected by the court in dynastic China. In 1983, his graduation thesis and exhibition was not opened to the public because authorities deemed the contents “not fit in with official tastes.”[31] Chinese artists had consumed all of Western art history within ten years between 1980 and 1990 to catch up to the West, so that the problem that they faced was similar to artists from the West: how to break the canon of art history? Huang’s solution is simple but effective: create a version of art history that is not written, but “created” by human action to destabilize the art history canon.

This work is said to reflect the intellectual development of Chinese contemporary artists from imitating the West to fabricating their own conceptual approaches. Fei Dawei writes that Huang Yongping has created a radical and comprehensive theory to shift thinking about art.[32] His decision to destroy two classics of art history that were available in China is to challenge the projection of China to the West, and the West’s projection to China. In fact, Huang’s paper presented at the “Annual Conference on Aesthetics” in Fujian suggested that there is not yet modernism in Chinese painting, even though “intrinsic links exist between Western modern thought and Oriental traditions.”[33] Huang Yongping gathered from Western postmodern philosophy that the West was coming close to China, and Huang asks, “Why not art?” His first step was to identify commonalities between Chinese and Western culture, as Donatien Grau writes, “[Huang] plays on the commonplaces of each civilization, constituted as such. There are hints of incisive rhetoric in his approach: it is through commonplaces that we come to knowledge”[34] Like a map reader, Huang looks at a cultural map of the world and circles overlapping zones with his artworks. Huang theorizes that identity is built by one’s experience in life; hence, a person from the West could have a similar method of comprehension as a person from China, if they went through the same experiences. Huang mentioned in an interview that he put the books in a washing machine quite spontaneously; it was a magical instrument that cleaned clothes automatically, and he wanted to “express an attitude.”[35] Huang added that he had a very shallow understanding of the concepts discussed in A Concise History of Modern Painting. Hence, Huang washed the two books together to express his frustration and desire for something to be revealed to him. The result, as Fei Dawei explains, is an end-product that “does not follow any method, or logic…not about replacing one tradition with another, but rather about two cultures chaotically overlapping one another after their original structures have been pulverized.”[36] After the books have been mangled, the work is more than an expression of collision between East/West and contemporary/classic; it is about the destruction of categorization, a declaration that all art history leading to this point is relativistic and meaningless. Like greater events of human history, art history is not about individual entries or movements, but its ability to fit into the larger narrative of human history: the development of agriculture, iron-casting, the Mongol invasions, etc.[37]

Another series of works related periodically and thematically to A History of Western and Chinese Art Washed in a Washing Machine for Two Minutes are the roulette paintings. For this series, Huang wrote a manual “Paintings Made Following a Procedure Yet Unrelated to Me (Nonexpressive)”[38] with specific instructions about the design of the roulette wheel and procedure. Inspired by the I Ching and its system of matching certain geometric arrangements with meanings, Huang created a set of instructions taken from art history textbooks, the dictionary, and other books.[39] Then, he spun the wheel to determine which color and type of paint to use, and how and where to paint. When asked about divination, Huang explained, “The way that a coin or a die falls….as if your eyes were closed all allow the action to be free from the intervention of judgment made by the eyes and the brain.”[40] By removing the conscious effort of choosing color in painting, and relegating it to laws of probability, he has made the process of art-making and the history of art a non-visual and non-aesthetic living process. The result painting bears visual similarities to expressionism, but it is achieved through a completely, anti-style and anti-movement method. In later iterations, Huang added throwing the dice, lottery tickets, and other methods of divination and chance.

Huang Yongping’s spectacular rise to international recognition post-1989 ran the risk of turning him into a hypocrite. When he lived in China in the 1980s, despite the relative freedom for artists to organize exhibitions for their works, he tussled with official art authorities with iconoclasm and non-political rebellion. With the worsening political situation in 1989, Huang Yongping opted to stay in France after his participation in the Magicien de la terre exhibition. In the Western world, Huang met other challenges relating to the exhibition. He described exhibitions as problematic because an exhibition always presents a partial truth despite best efforts to be “complete.” [41]Thus, his future work became entirely based on commissions for a public audience.

THE BAT PROJECT

U.S. PLANE IN CHINA AFTER IT COLLIDES WITH CHINESE JET

April 1, 2001 — A United States Navy spy plane on a routine surveillance mission near the Chinese coast collided on Sunday with a Chinese fighter jet that was closely tailing it. The American plane made an emergency landing in China, and the United States said it was seeking the immediate return of the 24 crew members, all said to be in good condition, and of the sophisticated aircraft and all its intelligence equipment.–The New York Times, in print, April 2, 2001

It is the 21st century. Huang Yongping looked back at a fully modernized China that had recently become integrated into the World Trade Organization. However, China’s re-entry to the world could not happen without a major incident. On 1 April 2001, a Chinese J-8 fighter jet collided with an American EP-3 surveillance plane over the South China Sea, near Hainan Island. The collision killed the Chinese pilot and forced the damaged American plane to land. The incident became the first major international crisis of newly inaugurated U.S. President George W. Bush.

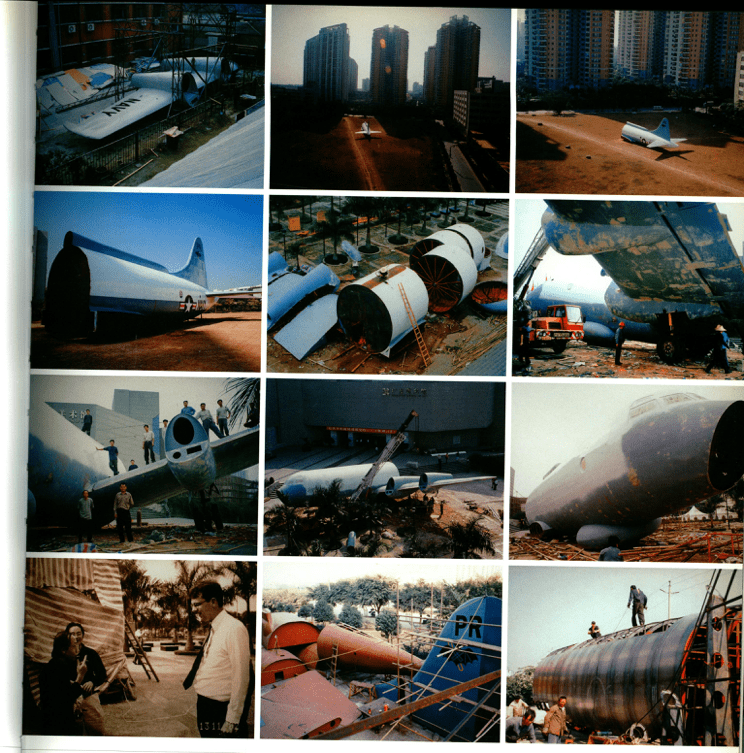

In early 2001, Huang received a commission by the OCAT Shenzhen, which had planned a joint exhibition between China and France to showcase works by Chinese and French contemporary artists. He developed the concept for the exhibition in his journal on 29 May, 2001, after reading about the peaceful resolution of the Hainan Island Incident. Huang wrote down his thoughts prior to the Bat Project: though the issue would be peacefully resolved, Huang wanted to “…keep this event going in China, however, to make it ‘unfinished.’” While collecting newspaper clippings and detailed engineer’s schematics of the plane, Huang in July 2001 expressed his intention to fabricate a life-size replica of the plane’s tail to Huang Zhuan, curator of the He Xiangning Art Museum. At the time, Huang Zhuan was supportive, and even sounded optimistic; he wrote that the work could “provoke a series of changes in cultural rules and the national psychology,” and that the work showed China’s ability to resolve the accident peacefully. In October, Huang’s work was halted, and to Huang’s great chagrin the work was changed without his permission to a nearby public park, where the tail of the plane was turned upright to resemble a tower. In April 2002, Huang wrote a letter to Ren Kelei, the CEO of the Overseas Chinese Town Corporation of Shenzhen to express his disapproval:

Now the situation is like this: the rear portion of the plane has been erected vertically, like a tower; the horizontal and vertical stabilizers of the tail have been pulled apart and stuck into the ground; the fuselage portions have been taken apart and placed on top of fake rocks made of concrete. And flowers have been planted all around this. The whole work is totally distorted beyond recognition.

At the same time, he received an offer from the Guangdong Museum of Art, which had heard about the controversy and wanted to include the Bat Project in the First Guangzhou Triennial of Contemporary Art. Professor Wu Hung, then the curator of the museum, discussed specifics of the sculpture with Huang Yongping in September 2002, and Huang decided to make a life-size replica of the fuselage and wing. Again, the Guangzhou Museum suddenly removed Huang’s artwork from the exhibition and catalog in late 2002 even though the fabrication of the fuselage and wing had been finished. In 2003, an independent land development company teamed up with an independent curator, seeking permission to display the Bat Project in Beijing. All seemed to be well this time; Huang’s original Bat Project finally opened to the public in Shenzhen after nearly two years. Then, the Beijing commission fell through when Beijing authorities refused to grant a safety permit that the construction company required to move the fabricated cockpit to its exhibition location. Finally, the drama concluded with irony when the complete work was displayed at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis in August 2005.

In the Bat Project, Huang Yongping developed and managed the idea over a period of four years. By the time of its fourth and only successful implementation, a common series of happenings became well-established. First, Huang’s name was removed from the catalogue and exhibition. In Shenzhen and Guangzhou, not only was Huang’s name removed, but the French consulate also withdrew its official endorsement of the event. Second, the actions of the Chinese and French authorities agitated Huang’s colleagues from China and France, who co-signed letters of protest. In a letter sent on 12 November 2001, the artists criticized that censorship of the Bat Project was an “intolerant, unjust, and laughable action.” In another letter sent in September 2002, the artists wrote that banning the Bat Project “violates the Chinese art system, which is just growing up, it violates the image of contemporary China and it also violates the image of the democratic Western countries.”[42] Third, the motivation behind each cancellation was always ambiguous. Huang did not know who or what led to each exhibition’s cancellation, but discovered only vague explanations after years of self-directed investigation. Huang gradually learned that the museum in China and French cultural emissaries had been pressured by higher-ups from the U.S. and China, which was expressed through a sequence of seemingly unrelated actions: an embargo of works by French artists at the Shenzhen-Hong Kong border; protests by French members of parliament; the French consulate’s questioning of the exhibition’s French curator; and Raymond Rocher, cultural attaché of the French consulate, declining to attend the Guangzhou Triennial in 2001. In the end, Huang could not attribute the reason for cancellation to a person, authority, or even a country. The inexplicable effect of the show’s cancellation (a cultural event) due to pressure from an international incident (a political event) attacks the norms of international relations, and reveals that censorship functions differently in China and in the West. Huang revealed through the Bat Project neither nationalism nor anti-American sentiment (a common reading of the work), but rather a systematic failure of the art museum and its experts when they give way to diplomatic pressure.

Huang wrote, “All political events are easily forgotten…but art is not politics; it tries to stand up against the course of time and to allow something that is supposed not to be kept to stay there.” When asked if the Bat Project was a political work, Huang declined but added, “”What interests me are tactics, strategies, actions, and provocation that are related to politics.” In the Bat Project, Huang revisits the theme of the fragility of labels, now applied in the realm of international relations. Consequently, Huang launches a critique against the separate realms of international culture and politics, which reveals that an interconnected world does not make misunderstandings less threatening to global stability. The strategy he applies in the Bat Project engaged fellow artists, art critics, politicians, diplomats, and military generals even though an airplane is “…neither humiliating nor encouraging for people…no connection with the so-called national passion; it has only the accuracy and coldness of engineering techniques, a perfect aviation form, an immense volume, and hard and sleek surfaces.”[43] The result is the work derives its meaning from the participants provoked by its subject matter rather than from its physical appearance or materiality. As Huang dissected the EP-3 to reveal its secretive internal components, the Bat Project exposed deep resentment that exist underneath global partnerships, as Huang writes, “…power at its peak is always linked to its decline, and the omnipotence of high technology cannot be separated from its incapacity…”[44]

CONCLUSION

Looking back, the Bat Project currently in the Walker Art Museum in a warmly lit room generates an extreme sense of artifice.[v] In another room, several sticks hold up several filmstrips of photographs of the various incarnations of the Bat Project, so that the installation resembles a tent. Former controversy surrounding the plane has become silent. In effect, the work has suffered the same fate of aestheticization that Huang railed against when his host in Shenzhen had moved the Bat Project to a landscape garden. To understand the Bat Project, visitors are compelled to read the catalog and description unless they recognize the allusion, precisely the opposite of Huang’s intended effect when he wanted the work to “speak for itself” when “connected in an organic way with its venue.”[45]

In May 2016, Huang Yongping returned to the subject of his immigration from China to France with Empires, a visual behemoth created in the Grand Palais in Paris for Monumenta 2016. A skeleton of an imaginary beast spirals among countless shipping containers with the words “capital” printed on the containers in English and Chinese. Above two towers of perilously stacked containers perches Napoleon’s Bicorne hat. Asked about the shape of the creature, Huang referenced that the serpentine shape of the sculpture resembles Xiamen at the beginning of the 1990s, when industrialization paved the way to trade between China and the world. [46] Huang felt a sense of affinity for both Paris and Xiamen as transformational cities in the world; Paris, as a city of old Europe that was once the cultural capital of the world, and Xiamen, a city of a “new China” that is becoming the economic capital of the Taiwan Straits. Yet, Huang says that globalization comes at a cost, for the beast that glides among the containers is an expression for thirst for power and greater possibility of conflict among participants of globalization.

In the recent decade, Huang Yongping made artworks that made specific references to Chinese landmarks or issues confronting China’s position in relation to the West. As a great “eraser of boundaries,”[47] Huang reveals the vulnerabilities of civilization. The mid-20th century through early-21st century was the struggle between Communism and everything else; a new struggle will come in the future. As Hou Hanru writes, “All of [Huang Yongping’s style of art production] points to the ultimate destiny of life: that everything in the world is in constant flux and that life, turning around in endless circles, is an eternal dilemma, while destructive acts like wars are probably part of the process of regeneration, of creating a new world, and that this makes the efforts of the ‘multitude’ meaningful.” The struggle of the 21st century would be between pragmatism and idealism, globalism and isolation. In Huang Yongping’s art, the object is secondary to thought. With the proper concept, the object ceases to matter because he has successfully taken the conversation away from history of art into the history of human civilization. And his technique of constant comparative criticism, between East and West, makes us see more clearly the fragility of human institutions and labels. Yet among various positions that individuals take on specific issues, there is an essence that is constant that Huang hopes that we can achieve through his art.

***

[1] “nonsense, n. and adj.”. OED Online. December 2016. Oxford University Press. http://ezproxy.library.nyu.edu:2639/view/Entry/128094?rskey=PLl4Xe&result=1&isAdvanced=false (accessed December 18, 2016).

[2] Fei Dawei, House of Oracles: A Huang Yong Ping Retrospective (Minneapolis, MN: Walker Art Center, 2005), 9

[3] Fei Dawei, House of Oracles, 10

[4] Lu Peng, A History of Art in 20th Century China (Milano: Charta, 2010), 875

[5] Huang Yong Ping, House of Oracles: A Huang Yong Ping Retrospective (Minneapolis, MN: Walker Art Center, 2005), 36.

[6] Huang Yong Ping, House of Oracles, 36

[7] Huang Yong Ping, House of Oracles, 34

[8] “Frank Stella and Huang Yongping in Conversation,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed December 2, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CPB2dt5TC8w

[9] “Interview with Huang Yongping on Chinese contemporary art in the 1980s, by Asia Art,” Asia Art Archive, accessed December 2, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T50aruFuEKU

[10] Huang Yong Ping, House of Oracles, 34

[11] Fei Dawei, House of Oracles 6

[12] Huang Yong Ping, House of Oracles, 46.

[13] Benjamin Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 2006.), 6

[14] Qi Luo, China’s Industrial Reform and Open-Door Policy, 1980-1997: A Case Study from Xiamen. (Aldershot, Hampshire, England: Ashgate, 2001), 46.

[15] Qi Luo, 47

[16] Qi Luo, 50

[17] Qi Luo, 55

[18] Qi Luo, 58

[19] Thierry Raspail, Donatien Grau, et. al, Huang Yong Ping: Amoy/Xiamen (Paris: Kamel mennour, 2013), 92

[20] Fei Dawei, House of Oracles, 6

[21] Huang Yong Ping, House of Oracles, 38

[22] Huang Yong Ping, 77

[23] Huang Yong Ping, 38

[24] Huang Yong Ping, 46

[25] “Interview with Huang Yongping on Chinese contemporary art in the 1980s, by Asia Art Archive”

[26] Huang Yong Ping, 35

[27] Huang Yong Ping, 35

[28] “Frank Stella and Huang Yongping in Conversation”

[29] Fei Dawei, House of Oracles, 6

[30] Fei Dawei, 6

[31] Huang Yong Ping, House of Oracles, 34

[32] Fei Dawei, 6

[33] Huang Yong Ping, 34

[34] Thierry Raspail, Donatien Grau, et. al,, Huang Yong Ping: Amoy/Xiamen, 94

[35] “Frank Stella and Huang Yongping in Conversation”

[36] Fei Dawei, 8

[37] Thierry Raspail, Donatien Grau, et. al,, 75

[38] Huang Yong Ping, 65

[39] Huang Yong Ping, 48

[40] Huang Yong Ping, 50

[41] Hou Hanru, House of Oracles, 12

[42] Huang, Yong Ping, and Philippe Vergne. House of Oracles, 68

[43] House of Oracles, page insert

[44] House of Oracles, page insert

[45] House of Oracles, page insert

[46] Grand Palais, MONUMENTA 2016 HUANG YONG PING EMPIRES. Paris: Kamel mennour.

[47] Thierry Raspail, Donatien Grau, et. al., 96