In a world full of technological, medical and scientific advances, one might be surprised to learn that religion — societal concept conceived during a time when the common cold was a death sentence and freezing to death within one’s own home was a fully possible scenario — is still a defining presence within the present.

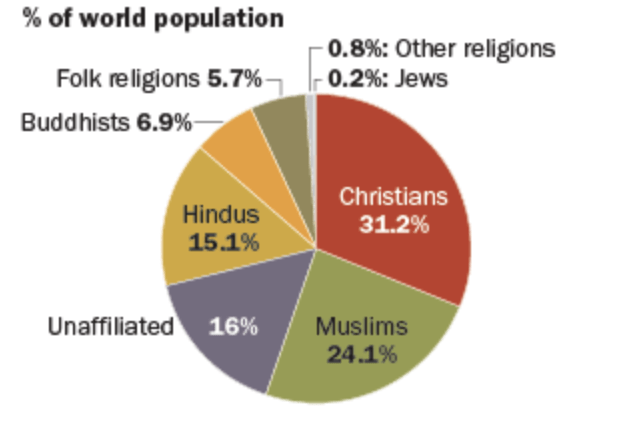

Then again, that “one” person who questions this represents an incredibly small percentage of the current world’s population — 16% to be exact. For this exact reason, religion and the state of our world must be considered in tandem if we are to resolve the current environmental crisis that has begun and only will continue to disastrously intensify and destroy whole countries, communities, and cultures.

I don’t declare this statement lightly — after all, I belong within that 16 percent, as an atheist. Frankly, I believe religion has no place within topics of great societal importance. such as political or economic policies — separation of Church and State is a thing after all — but desperate times call for desperate measures. In a time when report after report declares the Earth and its inhabitants as all basically doomed if carbon production and other climate change catalysts are not immediately halted on an unprecedented scale, I think we can take all the help we can get within the climate justice movement — as close to that 84 percent as we can reach.

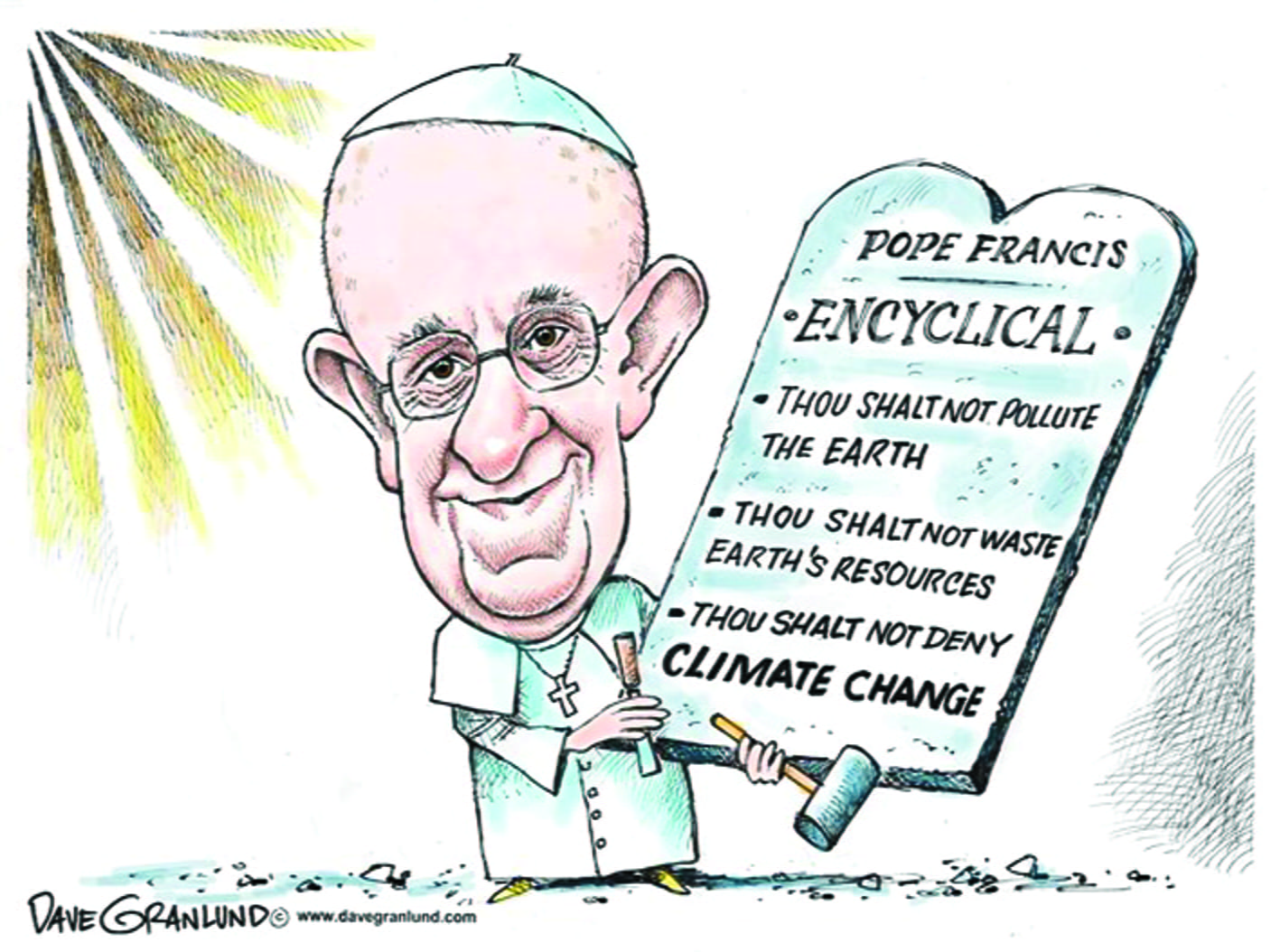

While reading The Week’s feature article entitled “How does religion influence our thoughts on climate change?“, I was relieved to learn that a surprisingly large amount of religious organizations and its leaders have asserted that we have a crucial role to play in order to protect the Earth, rather than destroy it. This assertion is grounded in a distinct interpretation of a religious notion known as the “dominion mandate”, a notion that has sparked tension and debate over centuries and across religions. One version of dominion, the one which Pope Francis outlines within the Climate Encyclical, Laudato si’, categorizes humans as superior to non-human animals, but also acknowledges that this does not allow us the right to exploit natural resources without limit, regardless of profitability. Most other religious systems agree with this sentiment in some form or another, such as Buddhism (Bhutanese Buddhism specifically), Islam (except Wahhabism), and inherited cosmovision (autonomy of nature, collective rights to sacred lands, etc), a view held by indigenous peoples worldwide.

So why then is religion in countries such as America, Saudi Arabia and China attributed to climate change in such a negative form? Well, to put it simply, it all comes back to politics and greed.

All three of these countries are economic superpowers due in no small part to the fossil fuel industry, which relies on constant utilization (and therefore, destruction) of natural resources. They are also vastly religious nations, but their interpretation of the dominion mandate is markedly more fiscally motivated than it is environmentally friendly.

The inherent problem with religious texts in a modern world is that we are incredibly separated from its original source time-wise, so our interpretations and translations may not be quite as accurate and holy as is perceived. The passing of time always leaves room for information gaps, and we must question who was (and is) left in charge of filling in these blanks.

In America, white Christian evangelicals make up the majority of climate change deniers, whereas non-white evangelicals in the U.S., and evangelicals in other countries are much less likely to speculate on its credibility. It does not seem coincidental then, that this distinct faction of evangelicals, is one of disproportionately high socio-economic and -political status and influence.

It is clear to me that we must appeal to religious people if we want to see any real change within the climate justice movement. It is also clear that we must call out instances in which religion is skillfully inserted within political conversations by those who financially benefit from the fossil fuel industry (such as politicians themselves and their fiscal supporters). No matter how much they explain away their greedy practices and utter disregard for the implementations of environment protection, we owe it to ourselves to stand up for the land in which we inhabit. Regardless of whether we identify as a believer in the dominion mandate or not, as Buddhist or Christian, Republican or Democrat, American or Indonesian, you name it — we will not have an Earth left to inhabit if we don’t do something, and fast.

Alice,

You are a force of nature – and intellect.

This is another well thought out, well-written post.

If you have time, would you post this under your pseudonym on the greenworld.NYC site? People should be able to read what you write.

Prof. Peter Terezakis