We plan to visit each of the sites titled in blue (and noted with an asterisk *) and do our best to visit them in the order they appear here. But, to keep on schedule, we will not stop at sites titled in black. We strongly encourage you to visit those we’ll skip — and, indeed, everything on the list — on your own!

Louis Valentino, Jr., Park and Pier

76 Van Dyke Street Brooklyn Clay Retort and Fire Brick Works Storehouse

Red Hook*

(adapted from Red Hook Water Stories, PortSide, Landmark Preservation Commission, Brooklyn Public Library, Waterfront Museum, Bowery Boys)

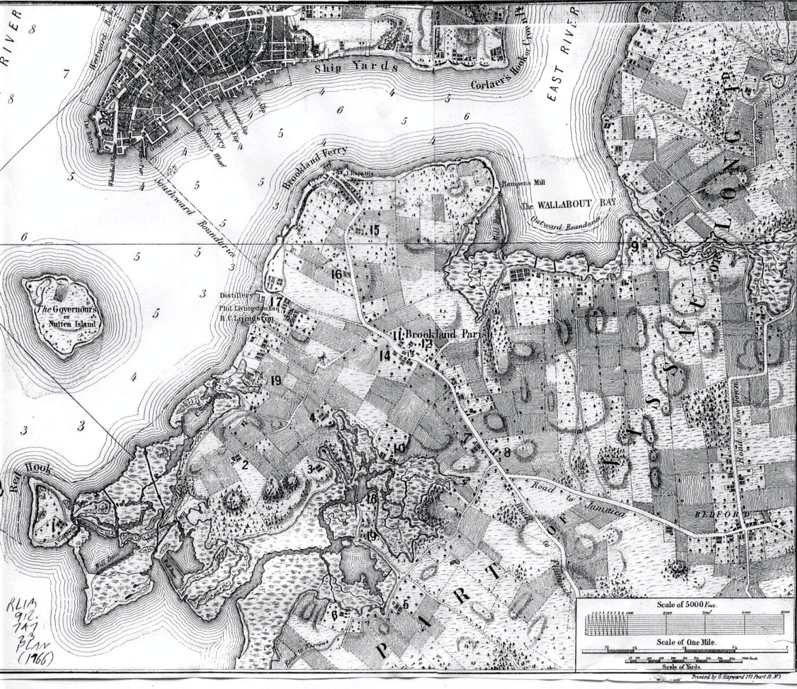

Lenape people are known to have populated Red Hook long before the first Dutch colonists arrived. “Lenapehoking” is the Lenape name for the Lenape homeland, which spans from Western Connecticut to Eastern Pennsylvania, and the Hudson Valley to Delaware, with New York City at its center. One historian suggests that Lenape people didn’t live year-round in marshy Red Hook but occupied the area primarily in the summers for hunting, fishing, collecting oysters, and growing vegetables. According to a report prepared for the Landmarks Preservation Commission, the indigenous Lenape people named the area Ihepetonga, meaning a “high point of sandy soil” but this is disputed since much of the Red Hook area is low-lying and the soil is red clay.

On May 27, 1640 Willem Kieft, the Dutch administrator for the colony of New Netherland, granted Frederick Lubbersen a patent to the lands “near Merechkawikingh about Werpos, reaching in breadth from the kil and valley that comes from the Gowanus…to the Red Hook under the express condition, that the savages shall voluntarily give up the maize land in the aforesaid piece.” There is no record of the Dutch Government or the Lenape leaders sanctioning this arrangement, but it appears to mark the beginning of European colonization in Red Hook. Red Hook became part of the town of Brooklyn in 1657, by order of Governor Peter Stuyvesant.

Buttermilk Channel

(adapted from Wikipedia, Red Hook Waterfront)

Buttermilk Channel is a small tidal strait in Upper New York Bay separating Governors Island from Brooklyn. Origins of the name are unknown but some people believe that the channel got its name because crossing it was so rough that farmers’ milk was churned into butter by the time their boats reached Manhattan. Another legend says that the choppy water looked like churned milk, hence the name. The name Buttermilk Channel appears on maps as early as 1776.

Atlantic Basin*

(adapted from the Red Hook Star Revue, by Connor Gaudet, and Brooklyn Public Library, Center for Brooklyn History)

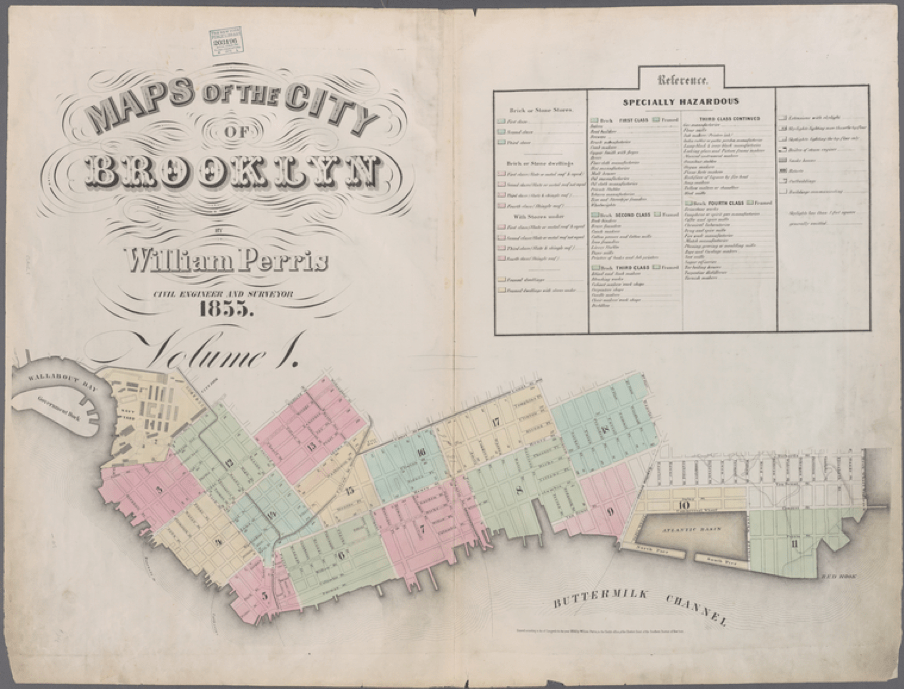

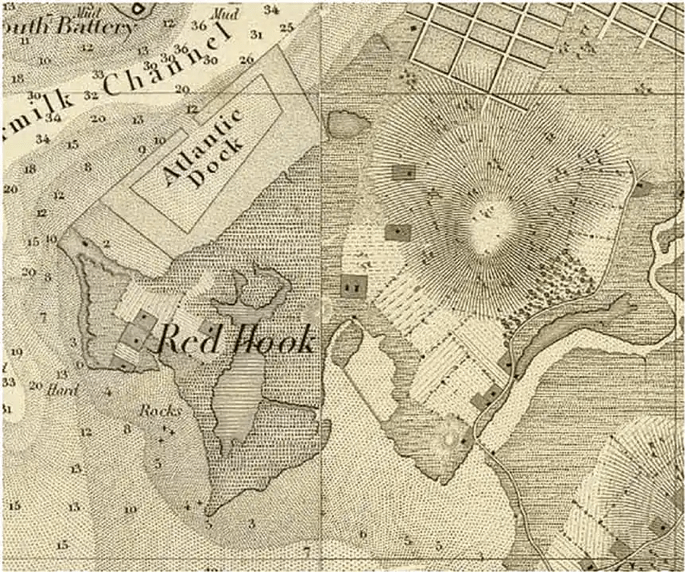

After the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825, shipping commerce increased dramatically in New York harbor. Soon Manhattan’s waterfront became a congested bottleneck, crowded with ships that sometimes had to wait weeks for a berth to become available for them to unload their cargo. The problem was related to insufficient dock facilities but also a lack of conveniently positioned storehouses near the docks. Brooklyn was well situated to take advantage of Manhattan’s dearth of space by offering new piers, docks, and conveniently located storage buildings. In 1839 Daniel Richards conceived the Atlantic Dock Company and began to develop the Brooklyn harbor shoreline by erecting a contained set of docks, warehouses, and a basin for deep-water ships. In order to allow larger vessels to enter the basin at all tides, the Atlantic Dock was constructed in the Buttermilk Channel, just beyond the marshes and inlets near Red Hook. Richards and his business partners extended the natural coastline by several hundred feet with fill from nearby Bergen Hill to connect to the newly-completed Atlantic Basin. Dock construction began in 1841, stone warehouses followed in 1844, and records show that a steam-operated grain elevator, the first of its kind in New York Harbor, was active by 1846.

Here is an anchor

Red Hook Terminals

Red Hook Terminals, 70 Hamilton Avenue, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from Red Hook Stevedoring & Terminal Operators, Waterfront Alliance)

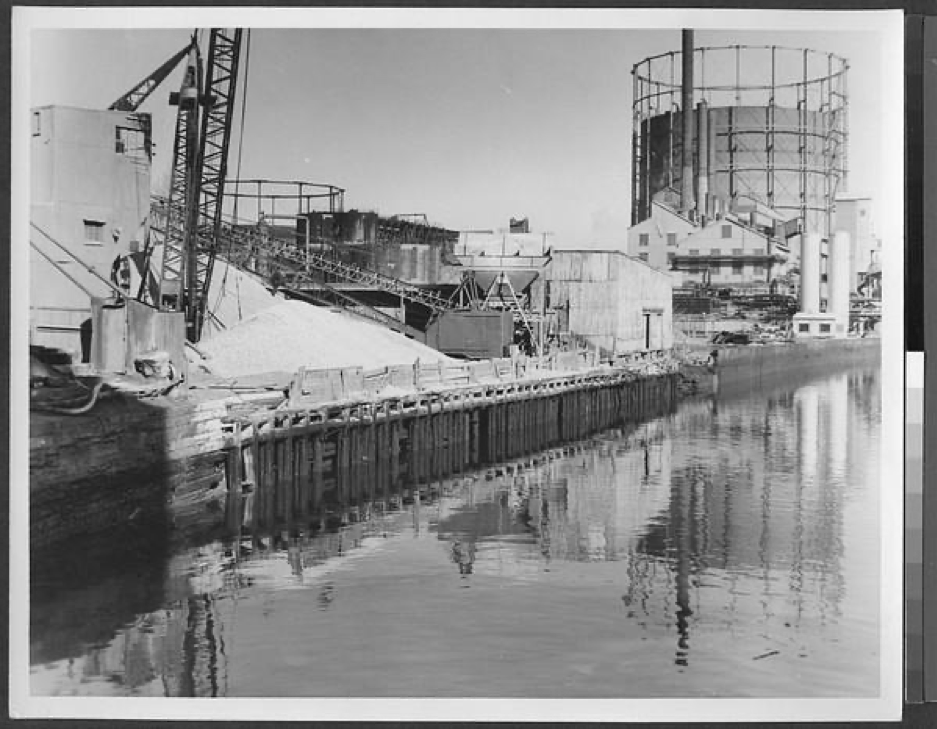

Red Hook Terminals is a terminal operator, stevedore, and cross harbor barge operator with two facilities in the Port of New York and New Jersey. Red Hook Terminals handles cargo and bulk commodities, such as road salt and stone aggregates as well as steel, lumber, palletized bananas, and containers. The terminal provides heavy lifts for yachts and autos. Red Hook Terminals leases its space from the Port of New York & New Jersey—the second largest port in the United States, after Los Angeles.

Brooklyn Cruise Terminal

Brooklyn Cruise Terminal, 72 Bowne Street, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from Wikipedia, NYCruise, NYC EDC)

The Brooklyn Cruise Terminal is an 180,000 sf facility located on the south side of Atlantic Basin. The Carnival Corporation, which owns the Cunard and Princess Cruise lines’ passenger ships, call the terminal their home port. The terminal—on land owned by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey and leased by the New York City Economic Development Corporation—is one of three terminals for ocean-going cruise ships in the New York metropolitan area. The terminal was converted from a 1954 freight terminal and was earlier the site of the Atlantic Basin Iron Works. The Brooklyn Cruise Terminal opened on April 15, 2006, following a $52 million investment by NYCEDC.

PortSide New York*

PortSide New York, Pier 11, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from PortSide, Red Hook Water Stories, National Register of Historic Places application)

PortSide New York is a maritime cultural center that is dedicated to enhancing New York City’s waterfront for commerce, recreation, transportation, culture and education. Through its advocacy work, youth and adult educational programs, job training initiatives, and ongoing historical research, PortSide promotes engagement with the waterfront and surrounding neighborhoods. Founded in 2005 by Carolina Salguero, PortSide directs many in person and online community-facing programs including the African American Maritime Heritage Program.

PortSide’s primary base of operations is the Mary A. Whalen, a 1938 petroleum tanker that is moored in Atlantic Basin. The Mary A. Whalen, formerly known as S.T. Kiddoo, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places as few vessels of her period, class, and integrity of original construction have survived.

The ship’s hull (172 feet long, over 31 feet wide) is constructed of welded steel plating with lapped strakes. She operated as a “bell boat” until her retirement from active service in 1994. On bell boats, the captain controls only the rudder to direct left and right movement; the throttle and engine are controlled by the engineer who responds to the captain’s signals via the sound of a bell. The Mary A. Whalen operated as a bell boat until her retirement.

Charles Deroko, a naval architect and restoration consultant who contributed to the application for inclusion in the National Registry, describes the technical advances that the Whalen represents. He writes, “Shipbuilders in the 1930s were unsure of the mechanical characteristics of welded joints and continued to join the hull plates as they had done with riveted ships. However, hull plates that were lapped and welded did not take full advantage of the weight savings and efficiency that welding had to offer. Plates that were butt welded, that is, welded edge to edge, not only saved weight by eliminating the plate laps, but also presented a smoother surface to the water thereby reducing hull resistance. Hull inspections have revealed that Mary A. Whalen has no riveted connections. This makes her historically significant as an early example of all-welded, lapped plate construction and a good representative of this period in shipbuilding.”

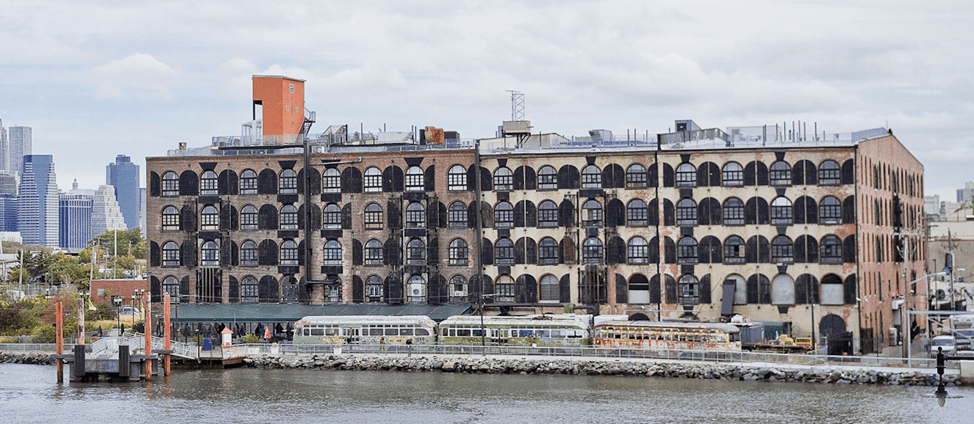

New York Dock Company Buildings

160 Imlay Street, 162 Imlay Street

(adapted from Brownstoner, by Suzanne Spellen, Curbed by Zoe Rosenberg, and Atlas Obscura)

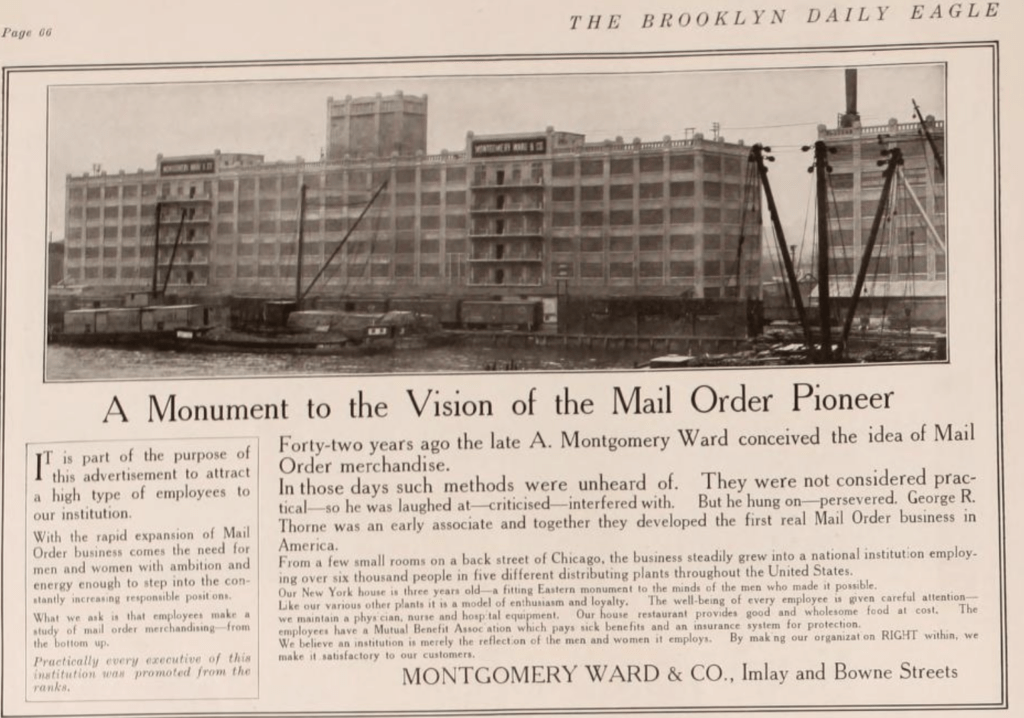

As part of the Atlantic Basin development, New York Dock Company envisioned fully coordinated infrastructure elements including bulkheads, docks, piers, railroad tracks, and storehouses. In 1912, the company needed additional storage facilities and began building two huge concrete warehouse buildings along Imlay Street. The structures, designed by Maynicke & Franke, who designed many other warehouses for the Dock Company, were completed in 1913. Even before construction was completed, the Dock Company announced that a single tenant, Montgomery Ward, the mail order giant, would occupy the entirety of 160 Imlay Street, over 220,000 square feet. The sister building was leased to smaller concerns. But, with the outbreak of World War I, the harborside spaces were in high demand for military support, so 160 and 162 Imlay Street became army bases and supply depots.

Today, 160 Imlay Street has been converted to luxury condominiums while 162 Imlay Street is an art storage facility managed by Christie’s, the auction house.

Pioneer Works

Pioneer Works,159 Pioneer Street, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from Pioneer Works, Vanity Fair)

Pioneer Works is a nonprofit cultural center that was founded by artist Dustin Yellin in 2012. The center’s mission is to foster innovative thinking through visual and performing arts, technology, music, and science.

Pioneer Works includes three floors of interconnected studio, performance, and exhibition spaces, which are intended to cultivate artistic and scientific collaborations. According to its founder, Pioneer Works was imagined as a place where artists, scientists, and thinkers from various backgrounds could converge and work together. The 25,000 sf red brick building that houses Pioneer Works was built in 1866 for Pioneer Iron Works. The factory, which manufactured railroad tracks and machine parts, was a local landmark for which Pioneer Street was named.

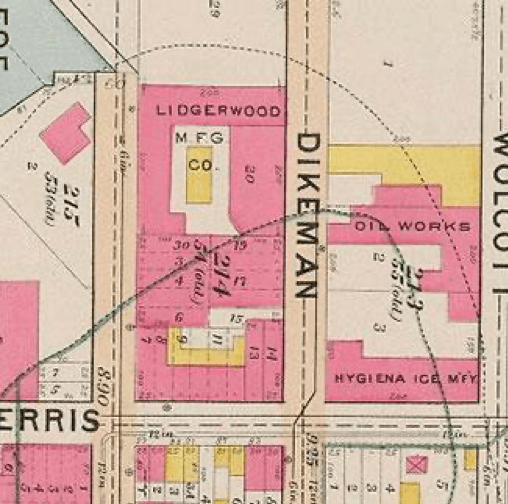

[RIP] Lidgerwood Iron Works

Bounded by Dikeman, Coffey, and Ferris Streets, Brooklyn, NY

For some history of the site and the importance of the Iron Works, Maggie Blanck’s website is a very good resource.

Credit: New York Public Library via Maggie Blanck

Louis Valentino, Jr., Park and Pier*

Louis Valentino, Jr., Park and Pier Ferris Street between Coffey Street and Van Dyck Street, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from NYC Parks Department and New York Times)

This park was named in honor of the decorated Brooklyn firefighter Louis Valentino, Jr. (1958-1996). Valentino joined the New York City Fire Department in 1984, first serving as a member of Engine Company 281, then with Ladder Company 147. In 1993, he was accepted to the elite Rescue Company 2 in Crown Heights, joining the ranks of the city’s most experienced and versatile firefighters. During his career as a firefighter, Valentino earned citations for bravery in 1987 and 1990. On February 5, 1996, Valentino died during the course of duty while searching for wounded firefighters in a three-alarm blaze.

Louis Valentino, Jr. Park and Pier was originally built in 1996 by the New York City’s Economic Development Corporation before becoming a city park in 1999.

Steve’s Authentic Key Lime Pie

Steve’s Authentic Key Lime Pie,185 Van Dyke Street, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from Keys Weekly)

A local businessman, Steve Tarpin and his pies enjoy a devoted following. While Steve’s enterprise is a relative newcomer to Red Hook, the pie itself claims a much longer lineage. Writing in Keys Weekly, David Sloan offers, “In the case of Key lime pie, we have good reasons to believe it started in the late 1800s with sponge fishermen (called “hookers”) pouring sweetened condensed milk on stale Cuban bread in a coffee mug, stirring in a bird egg and topping it with lime juice. Limes and condensed milk were staples of nutrition at sea, so there was nothing ground-breaking about this creation, and recording the recipe probably didn’t even cross the hookers’ minds. Consider, too, that making a Key lime pie as the fishermen did involved so few ingredients and such a simple process, that it would be the equivalent complexity of making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich today. No fancy recipe required.”

Dell’s Maraschino Cherries

Dell’s Maraschino Cherries,175-177 Dikeman Street, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from New Yorker, New York Times, Dell’s Cherry)

Established in 1948, Dell’s Maraschino Cherries have been a signature ingredient in American cocktails for nearly 75 years. A family-owned business, Dell’s processes more than 19 million pounds of cherries a year in their 38,000 square foot Red Hook facility.

Merchant Stores Building

Merchant Stores Building, 175 Van Dyke Street, Pier 41 Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from The Brooklyn Ink by Jennifer Sigl, Red Hook Waterfront)

Merchant Stores comprises two brick warehouses and occupies Pier 41. Built by Daniel Richards in 1873, Richards is also credited with developing Atlantic Dock and Erie Basin, the two waterfront improvements that brought about the emergence of Red Hook as a major shipping and warehousing center in the mid-19th century. Today, the buildings are home to the Liberty Warehouse events space, Flickinger Glassworks and many other businesses and manufacturing companies.

Flickinger Glassworks

Flickinger Glassworks, 175 Van Dyke Street, Pier 41, Brooklyn, NY

Flickinger Glassworks is a custom glass bending studio whose work includes custom architectural walls, storefronts, display cases, light fixtures and art installations, with most design and fabrication taking place in their Pier 41 location.

202 Van Dyke Street

This full block industrial site, home to many small businesses, sold in July 2022 for over $10 million. Current tenants include Hoek Pizza, Brooklyn Mill and Door and Light Blue USA, a lighting supplier. To find out more, Brooklyn Eagle’s website has reported the story.

Waterfront Museum

Waterfront Museum, 290 Conover Street, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from Waterfront Museum, National Register of Historic Places, Curbed)

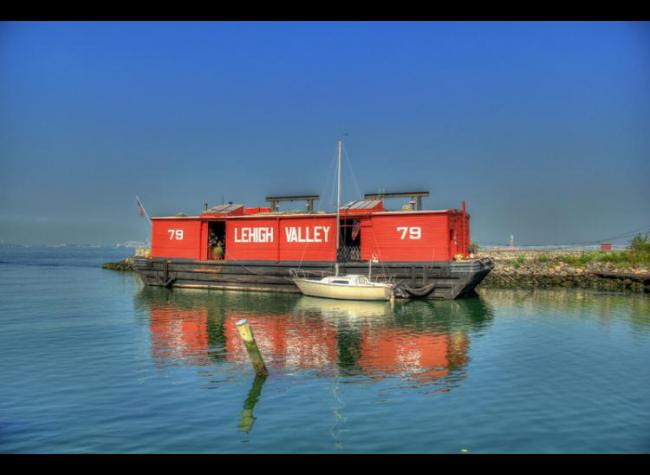

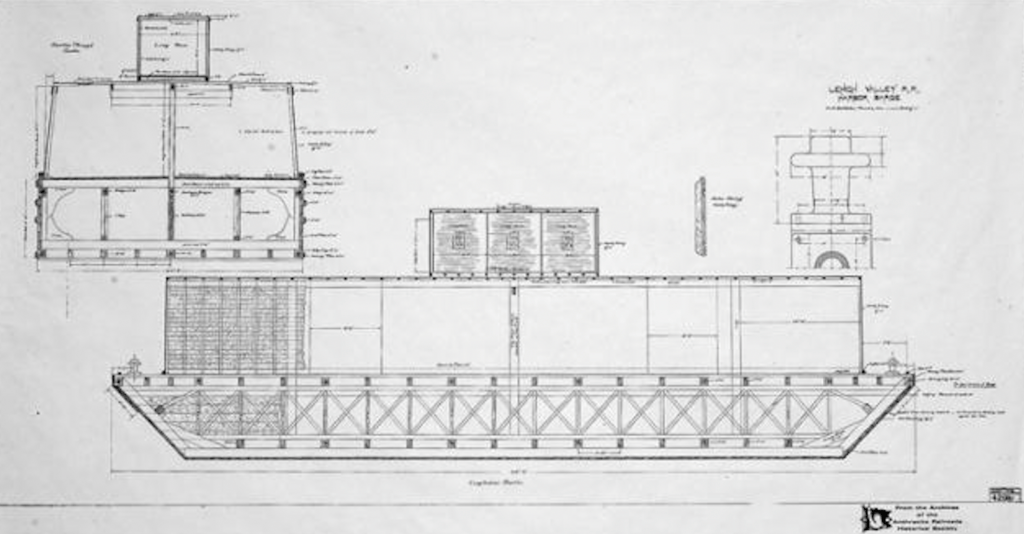

Lehigh Valley Railroad Barge No. 79 is the home of the Waterfront Museum and has been docked in the Red Hook area since 1994. The Waterfront Museum promotes waterfront access and educates visitors about maritime history.

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, L.V.R.R. No. 79, built in 1914, is an excellent, intact example of the wooden, flat-bottomed barges that were commonly used from the 1860s to the early 1980s in New York Harbor as part of the railroad lighterage system. The railroad lighterage system was essential to the successful operation of the Port of New York, as these small barges (lighters) moved cargo from rail terminals in New Jersey across New York Harbor. Because railroad tunnels and bridges had not yet been built, goods to be consumed in New York City and Long Island, as well as cargo to be loaded onto vessels for shipment overseas, first had to be transported by water to their intended destinations. To perform this function, railroad companies maintained large fleets of barges (lighters) and tugs.

The total number of craft working in New York Harbor when lighterage was at its peak is difficult to estimate since these vessels did not have to be registered. However, the Bureau of the Census of the United States Department of Commerce in 1916 (two years after L.V.R.R. No. 79 was built) provided the figure of 5,433 unrigged craft operating in New York Harbor. The great majority were barges like the L.V.R.R. No. 79 which carried “less than carload lots” of goods transferred from the railway freight cars to a barge by stevedores on New Jersey piers.

A 1918 Department of Labor survey found 89 barges with families onboard, 71 with a captain and wife. Companies encouraged family boats because married captains were thought to be more responsible and the boats tended to be better maintained. Insurers required a captain aboard a loaded boat at all times. This was easier if there were family members to handle shopping and errands. This floating population is an almost forgotten chapter in the social history of the New York Harbor. Barge operation was particularly appealing to young immigrant families. There was no rent to pay, and the railroad provided coal for the stove and kerosene for the lamps. Though not spacious, the L.V.R.R. No. 79’s living quarters were described as bigger and more airy than many other boats of the period. Furnishings located inside the cabin are believed to be original, including a table and stool, a closet, a shelf, and a berth with a mattress stenciled “L.V.R.R. 79.”

Fewer than a dozen covered railroad barges remain intact today. The Lehigh Valley Railroad Barge Number 79 is a rarity based not only upon her historical significance and social impact, but also upon her pristine state of preservation.

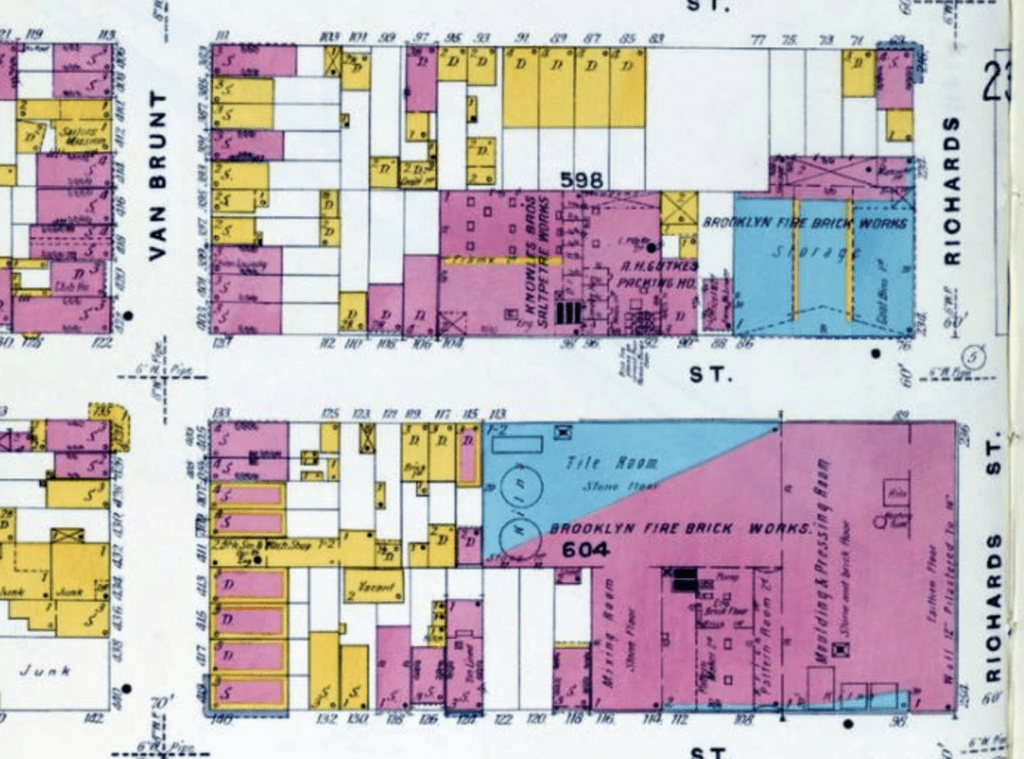

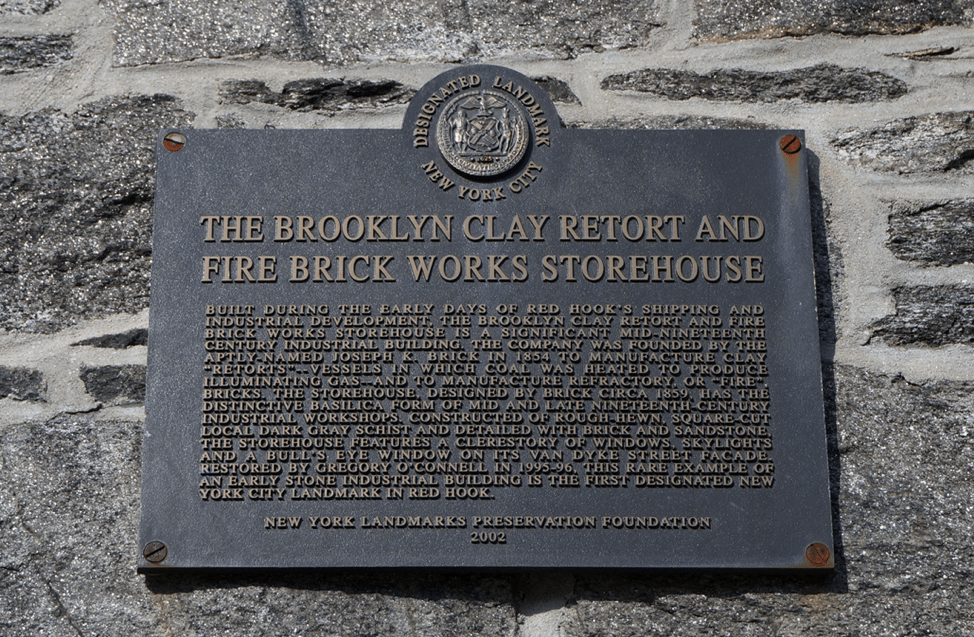

76 Van Dyke Street

Brooklyn Clay Retort and Fire Brick Works Storehouse*

(adapted from Landmark Preservation Commission report, Brownstoner, Atlas Obscura, Red Hook Star Revue, Red Hook Waterfront, Brooklyn Relics)

Built in 1859, this storehouse is the only surviving structure of the purpose built complex known as the Brooklyn Clay Retort and Fire Brick Company. Clay retorts and fire bricks made it possible to use burning gas as a source of light. Clay retorts are the airtight vessels where coal is burned to produce gas, while fire bricks serve as liners in heat-intensive environments such as kilns and furnaces.

The three-kiln factory continued production until the early 1930s. In 2001, the Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the storehouse a city landmark, becoming the first landmarked building in Red Hook. Today, the rough cut, dark gray schist building with brick and sandstone trim is the studio of artist Carol Bove.

Red Hook Stores

Red Hook Stores, 480-500 Van Brunt Street, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from New York Water Stories, Red Hook Stories, Architect Magazine)

The 5-story Red Hook Stores, originally known as the New York Warehouse Co.’s Stores, was built by Erie Basin developer William Beard in 1869. This building was part of the major expansion of storage and warehousing along the Red Hook waterfront after the Civil War. The fireproof building, which was built to sort and store cotton, changed ownership several times and was also known as Brooklyn Wharf and Warehouse Trust Stores and New York Dock Company Stores. The building originally served as a bonded warehouse, that is, a secured facility in which the government allowed goods to be stored or manipulated duty-free with taxes paid when goods left the building.

In 2006, the building was transformed into a mixed-use complex that combines apartments, live-work spaces, artist studios, and retail, all served by a co-generation plant which generates 90% of the building’s energy needs. Heavy timber joists were removed to create an interior courtyard and then milled for reuse as wood paneling at the entrance to each apartment. Most residential units retain original columns and masonry walls to showcase the industrial character of the historic building.

Brooklyn Waterfront Artists Coalition*

Brooklyn Waterfront Artists Coalition, 481 Van Brunt Street, 7A, Brooklyn, NY

Brooklyn Waterfront Artists Coalition, BWAC, is a non-profit, artist-run organization that supports Brooklyn artists with studio and exhibition space. BWAC’s mission is to assist emerging artists in advancing their careers and to present contemporary art in an easily accessible format.

MADE*

MADE, 141 Beard Street, 12B, Brooklyn, NY

MADE is a design/build practice that combines a design studio, fabrication workshop, and contracting team all under one roof. Founded in 2002, MADE has completed many high-end residential and retail projects and its work has been published in leading professional and popular design magazines.

Pier Glass

Pier Glass, 499 Van Brunt Street, 2A, Brooklyn, NY

Pier Glass specializes in custom glass blowing for designers, architects, and museums, including original designs as well as restoration and repair of existing glass items.

[RIP] Revere Sugar Refinery (formerly American Molasses Company and Sucrest Sugar)*

Beard Street at Richards Street

For some history of these businesses and the importance of sugar to Brooklyn and the region’s economy, Red Hook Waterfront and Red Hook Water Stories offer overviews and links to other resources.

[RIP] Todd Shipyards (formerly Robins Dry Dock & Repair Co.)

Current site of IKEA dock

For some history of the site and the importance of the Todd Shipyards and its predecessors, Red Hook Water Stories includes many links, including this oral history by Michael Gallagher, the last general manager of the shipyard before the site was sold to IKEA.

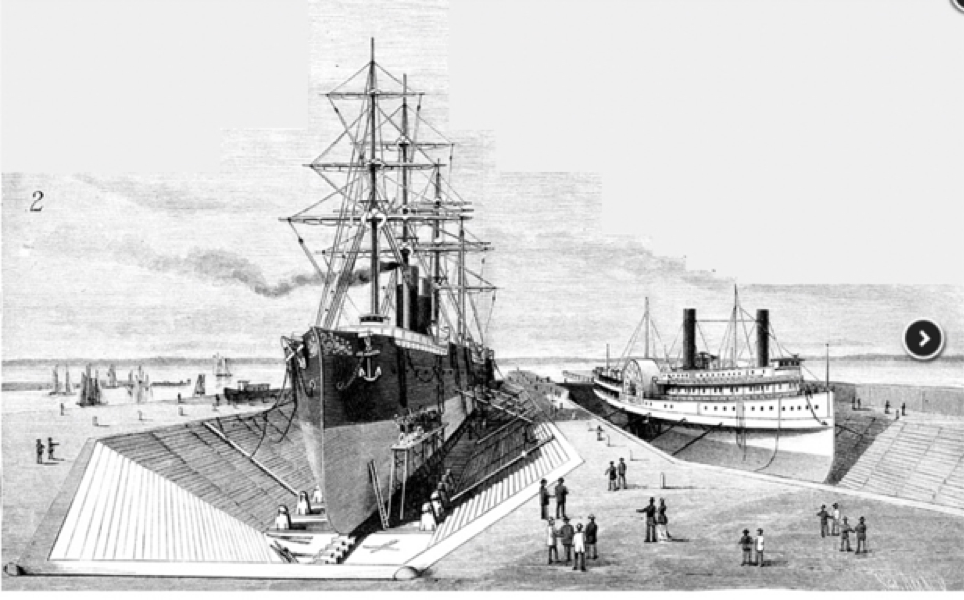

[RIP] Graving Dock No. 1

Current site of IKEA store

Graving Dock No. 1 was completed in 1866 to a design patented by James E. Simpson. A graving dock is a dry dock built into the shore whose perimeter can be sealed to allow water to be pumped out after a ship enters the dock. When the inspection and repairs are complete, water is allowed back into the basin so the ship can float out. Graving Dock No. 1 was used for ship repair until February 2005. A vigorous preservation campaign was mounted to save Graving Dock No. 1 but it was not successful.

Credit: Scientific American (January 13, 1883) via PortSide and Red Hook WaterStories

Erie Basin*

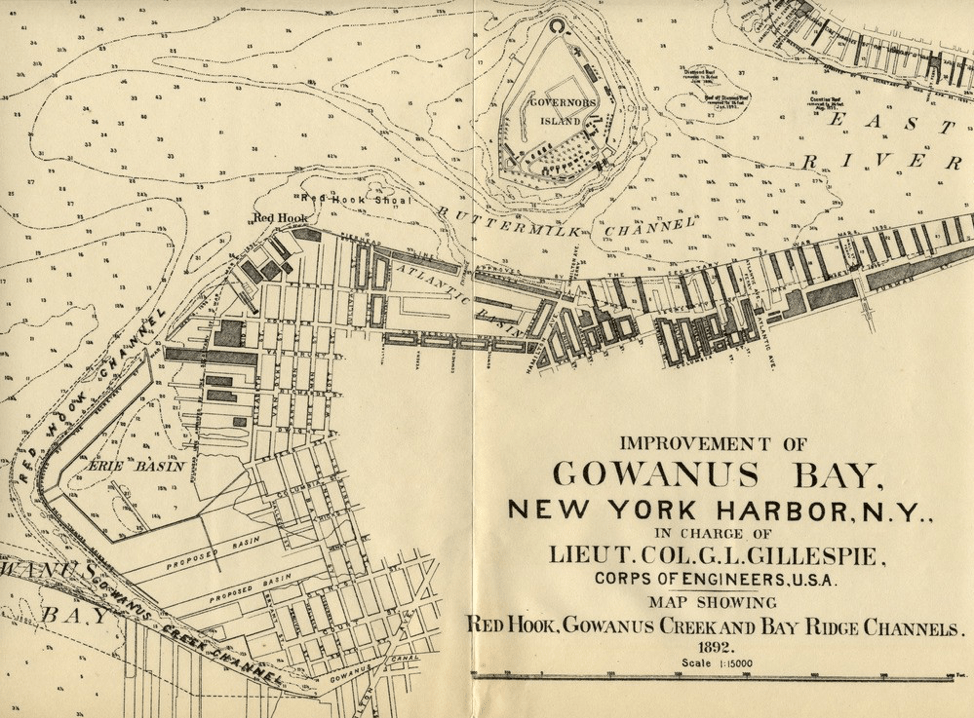

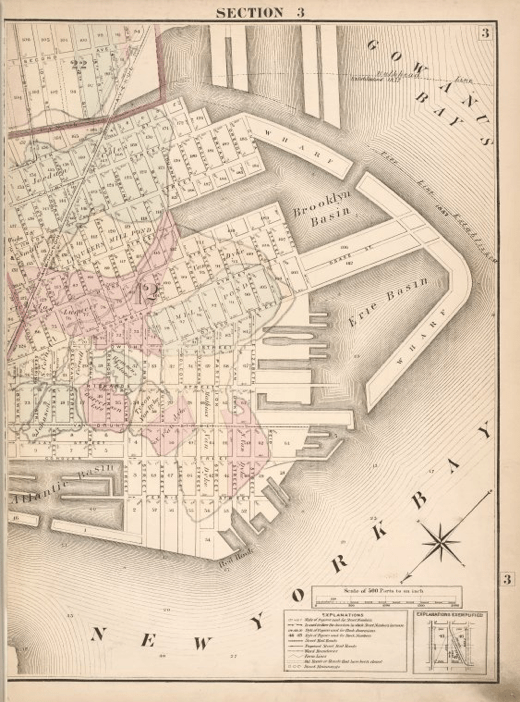

(adapted from Red Hook Water Stories, New York Times, Southwest Brooklyn Industrial Development Corporation, Erie Basin Bargeport, Hughes Marine)

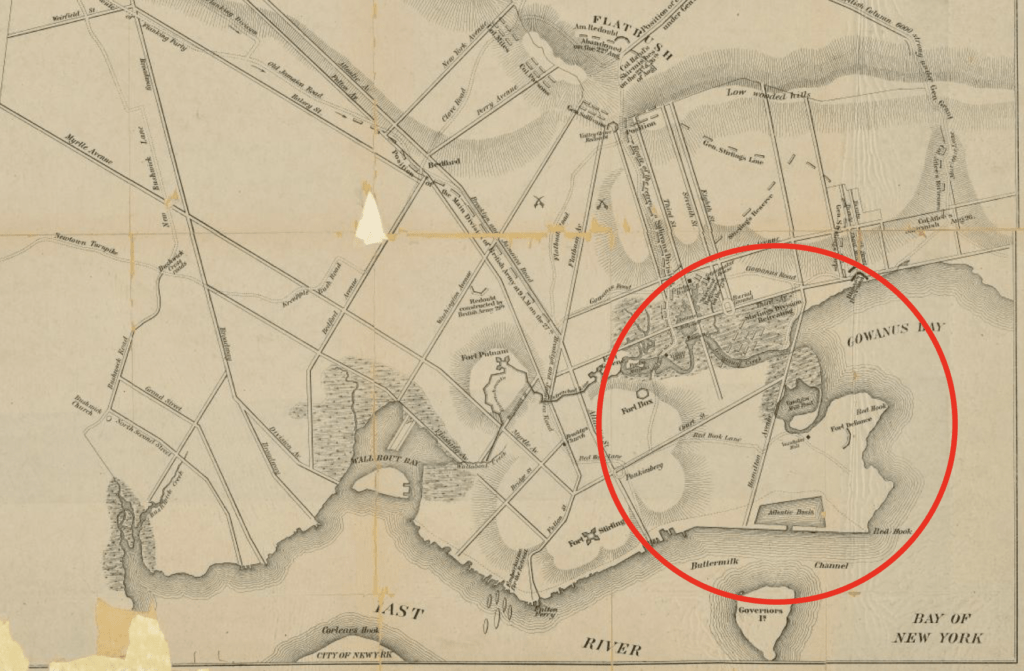

Erie Basin, at one time known as “the busiest place in the Port of New York,” is a large, man-made protected harbor in Red Hook that was completed in 1864. Jeremiah Robinson, George Robinson, and William Beard are credited with developing the shoreline to become the Erie Basin, whose U-shaped breakwater, well over one-half mile long, created a harbor to support piers, docks, dry docks, storehouses, and ships. According to historian Marcia Reiss, the hook that gives this part of Red Hook its distinctive shape was created with rocks from around the world, brought over by ships that used them for ballast and then replaced them with cargo.

Credit: G.L. Gillespie via PortSide

Following the success of the Atlantic Basin, the completion of the Erie Basin provided additional pier and dock infrastructure to establish Red Hook as the United States’ most important maritime hub. The Erie Basin was, from its completion until the early part of the 20th century, a major center of the world wide grain trade. As an active port, Red Hook attracted many manufacturing and industrial businesses to the area. By the early 1900s, the New York Dock Company became the largest employer in Red Hook, providing loading, unloading, and storage services.

Today, the two primary tenants of the Erie Basin are the New York Police Department and the Erie Basin Bargeport, the Northeast’s largest private berthing facility and one of the premier marine industrial parks in New York Harbor. The Bargeport, owned and managed by Reinauer Transportation, Inc. and Hughes Bros., provides a protected berthing facility for maintenance and repair of its barges, tugs, and marine equipment.

Credit: Brooklyn Public Library, Center for Brooklyn History

Initially, large breakwaters were proposed for both sides of Gowanus Bay to create two protected boat basins. Brooklyn Basin appeared on maps but was never built. Even without the breakwaters, this part of the waterfront was known as Brooklyn Basin until much of it was filled in the 1920s.

GBX Gowanus Bay Terminal*

Red Hook Grain Terminal

(adapted from New York Times by Christopher Gray, Red Hook Water Stories, Atlas Obscura by Hannah Frishberg, Wikipedia, Abandoned NYC by Will Ellis, Frieze by Jennifer Kabat, 6sqft by Dana Shulz)

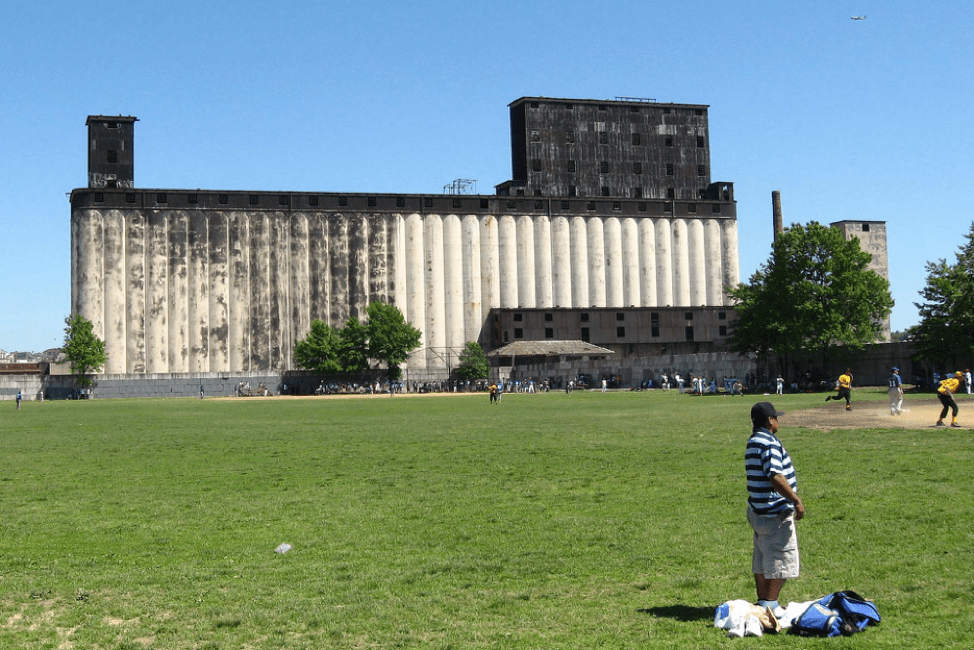

The Red Hook Grain Terminal, home to a towering, massive, abandoned concrete grain elevator, looms over the waterfront at the mouth of the Gowanus Canal.

The New York State Barge Canal Grain Elevator was completed in 1922 with a storage capacity of two million bushels in its 90-foot tall cylindrical silos. The Office of the State Engineer designed the 54-bin reinforced concrete grain elevator to serve a hoped-for increase of barge traffic carrying grain through the expanded Erie Canal and other upstate canals to the Port of New York. Called a “magnificent mistake” by famed New York Times “Streetscapes” columnist Christopher Gray, the grain terminal was redundant upon its completion in the early 1920s. By then, railroads dominated the transportation of grain from the Great Lakes and the Midwest. Additionally, ports in Baltimore and Philadelphia, with their less expensive docking fees, diverted trade from New York Harbor. The grain terminal failed to generate profit and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey assumed ownership in 1944, then decommissioned the structure in 1965. The Red Hook Grain Terminal is currently owned by John Quadrozzi, Jr., and managed as the CBX Gowanus Bay Terminal.

Credit: Will Ellis, AbandonedNYC

American grain elevators made a lasting impression on early 20th century European architects. German architect Walter Gropius published photographs of Buffalo’s grain elevators in the Jahrbuch Des Deutschen Werkbundes, Die Kunst in Industrie Und Handel in 1913. Ten years later, in 1923, Swiss architect Le Corbusier published Vers une Architecture and lauded grain elevators as “the first fruits of a new age.” German architect Erich Mendelsohn, who actually visited the American monoliths, wrote to his wife in 1924 in a state of reverie after seeing grain elevators in Buffalo, New York that “Everything else so far now seemed to have been shaped interim to my silo dreams…everything else was mere beginning.” Artists Bernd and Hilla Becher are famous for their photographs of large scale industrial artifacts, especially grain elevators. An exhibition of their photographs was on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the fall of 2022.

Loujaine

(adapted from Gothamist by Hannah Frishberg, Shipspotting, Skipshistorie, Newtown Pentacle by Mitch Waxman)

Loujaine’s former life was as a cargo and cement carrier. Built in 1966 in Nagoya, Japan, the ship, originally named Bahma, was configured as a bulk carrier for a Norwegian shipping company and featured 7 cargo compartments and 2 gantry cranes. Saudi Arabian company Arabian Bulk Trade (ABT) acquired Bahma in 1983 and converted the ship for cement handling, renaming her Abu Loujaine. Records show that she was moored in New York Harbor in 1985 for use as a “cement warehouse.” New York Cement Co. purchased Abu Loujaine in 1989. The ship was classified as a barge in 1998 and deleted from the registers of seagoing vessels, at which point she was renamed Loujaine under the flag of Panama. She does not appear on the Marine Traffic websites for real-time data of seagoing vessels.

RETI Center BlueCity*

RETI Center BlueCity, 701 Columbia Street, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from RETI Center, Penn Praxis)

RETI Center is a nonprofit organization whose programs prioritize environmental justice, social responsibility, and innovative design for coastal communities. RETI has several ongoing projects including BlueCity, Community Solar, and the Barge Field Station.

RETI’s mission is to support historically marginalized coastal communities in their efforts to reimagine and rebuild their waterfronts for a sustainable future. Through hands-on educational programs, RETI strives to bring young people from challenging backgrounds into positive and empowering learning environments while also partnering with other climate-positive initiatives. RETI seeks practical and innovative ways to address economic, social, and environmental injustices that affect coastal communities.

Red Hook Farms* (formerly Added Value)

Red Hook Farms, 30 Wolcott Street, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from Red Hook Initiative, Added Value, Wall Street Journal)

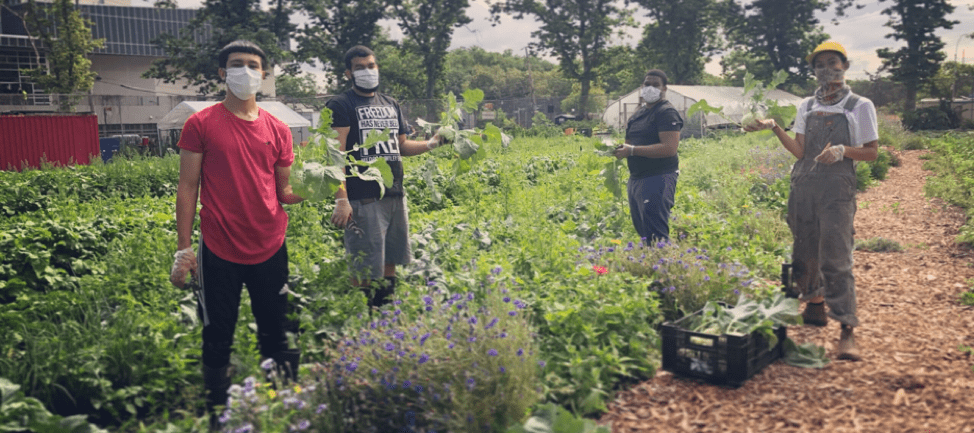

Red Hook Farms is a youth-centered urban agriculture and food justice program that operates one of the first urban farms built on public housing land. Red Hook Farms, a project of the Red Hook Initiative, is a 1.1 acre operation based at Red Hook Houses West and harvests over 5,000 pounds of produce each year.

The neighborhood around Red Hook Houses is considered a “food desert” with very few opportunities to purchase affordable fresh produce. This lack of access to affordable fresh produce has exacerbated public health inequities including high rates of obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and other health issues that are made worse by diets that are low in vegetables and fruit. Red Hook Farms has a mission to increase access to healthy, affordable produce and nurture the next generation of BIPOC green leaders. The Red Hook Initiative operates two urban farms and their programs include a teen farm apprenticeship, weekly farm stands, a CSA, Fresh Food Box, and workforce development training sessions. Domingo Morales, the inaugural David Prize winner (2020), mastered composting techniques as part of Red Hook Farms, extending David Buckel’s legacy.

Red Hook Houses East

Red Hook Houses West

Red Hook Houses, 62 Mill Street, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from Brooklyn Eagle, Wikipedia, Vassar Museum, LaGuardia & Wagner Archives)

The largest public housing complex in Brooklyn, Red Hook Houses opened in 1939 to support 2,540 families, or up to 9,500 persons. Consistent with the New York City Housing Authority’s (NYCHA) site planning strategy to create “towers in the park” such as those that had recently been completed at Queensbridge Houses, NYCHA created “super blocks” by demolishing existing buildings and closing six local streets. Red Hook Houses, built in two phases, included a total of 27 buildings between 2- and 6-stories high within a landscape that featured lawns, paths, seating, and dedicated play areas.

Credit: New York City Housing Authority Collection, LaGuardia & Wagner Archives

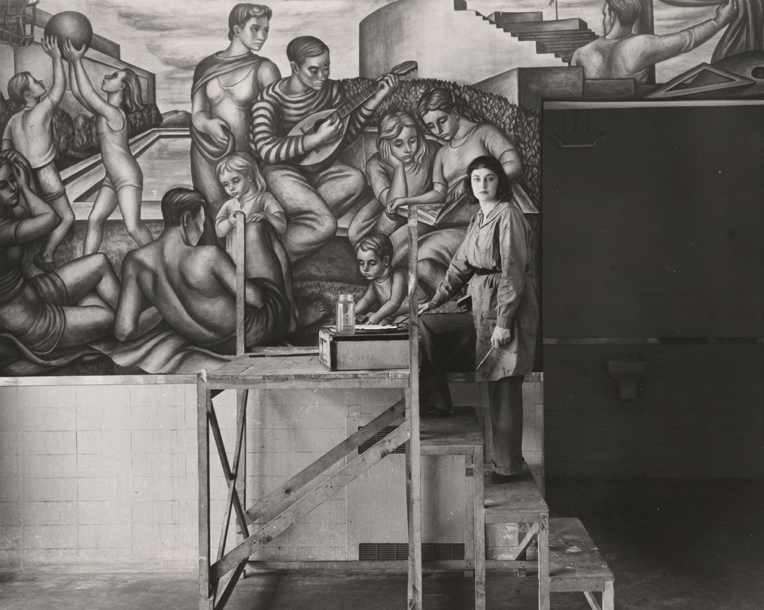

The first building of the complex to open was Building 24 at the corner of Lorraine and Columbia Streets. Brooklyn-born artist Marion Greenwood completed her social-realist mural Blueprint for Living in the lobby of one of the buildings.

Initial residents included white families of dockworkers but there is no indication of a Black tenant population among the earliest Red Hook Houses residents, even though records indicate that many waterfront workers were Black. A local newspaper, The Red Hook Star Revue, reports that 98.6% of current residents identify as nonwhite. Today approximately 8,000 people live in the complex, around 73 percent of Red Hook’s total population.

Red Hook Recreation Center

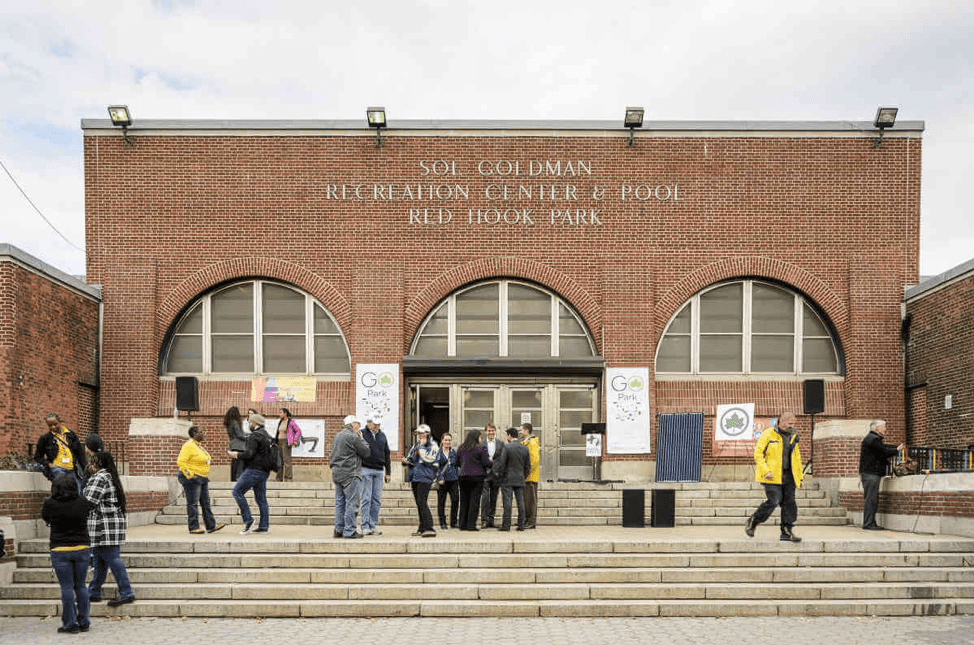

Sol Goldman Recreation Center, 155 Bay Street, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from New York Times, Landmarks Preservation Commission, The City, New York City Parks Department)

The Red Hook Play Center (Sol Goldman Pool), a large recreation center with both swimming and diving pools, is directly adjacent to the southeastern end of Red Hook Houses. The Center was completed in 1936 with funds provided by the Works Progress Administration during Fiorello La Guardia’s tenure as Mayor and Robert Moses as Parks Commissioner. In July 1934, the New York Times reported “Park Commissioner Robert Moses announced yesterday plans to provide twenty-three public open-air swimming pools in the more congested parts of the city.” The Red Hood Play Center was one of six large pools proposed for Brooklyn.

Credit: Stefano Giovannini via Brooklyn Paper

Moses’ justification for so many new public swimming pools was framed in response to his dismay at the waterfront’s environmental degradation. As quoted in a July 1934 newspaper article, Moses laments, “It is one of the tragedies of New York life, and a monument to past indifference, waste, selfishness and stupid planning, that the magnificent natural boundary waters of the city have been in large measure destroyed for recreational purposes by haphazard industrial and commercial development, and by pollution through sewage, trade and other waste. All citizens past middle age can remember the time when there was good swimming and even fishing in most of our boundary waters. That time, however, is past, and, as to most of our shore line, at least for many years to come, beyond recall. We must frankly recognize the conditions as they are and make our plans accordingly.” The Red Hook Recreation Center (as it is known today) was landmarked in 2008 and reopened in February 2022 after repairs following its significant damage during Superstorm Sandy in 2012.

[RIP] S. W. Bowne Grain Storehouse

S. W. Bowne Grain Storehouse Site, 595-611 Smith Street, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from Curbed by Nathan Kensinger, Red Hook Water Stories, VJ Rurbex)

The S.W. Bowne storehouse, completed in 1886, was part of a two-block-long complex on the western edge of the lower Gowanus Canal built atop filled marshlands. The warehouse buildings stored grain, hay, and feed; a feed mill was also located within the complex. The Report of the New York Produce Exchange of 1897 listed the S.W. Bowne warehouse as having capacity for 600,000 bushels and possessing one grain elevator. A 1913 advertisement touted the quality of Bowne’s Pure Grain Poultry Food, “Made A Little Better Than Seems Necessary.”

In March 2007, the National Trust for Historic Preservation placed the entire Brooklyn waterfront on its list of America’s most endangered historic places, and the Municipal Art Society launched an initiative (no longer active) to “Save Industrial Brooklyn.” But in the past 15 years years, many iconic Red Hook and Gowanus factories, warehouses, and refineries have been destroyed. S.W. Bowne warehouse was destroyed by arson in 2018.

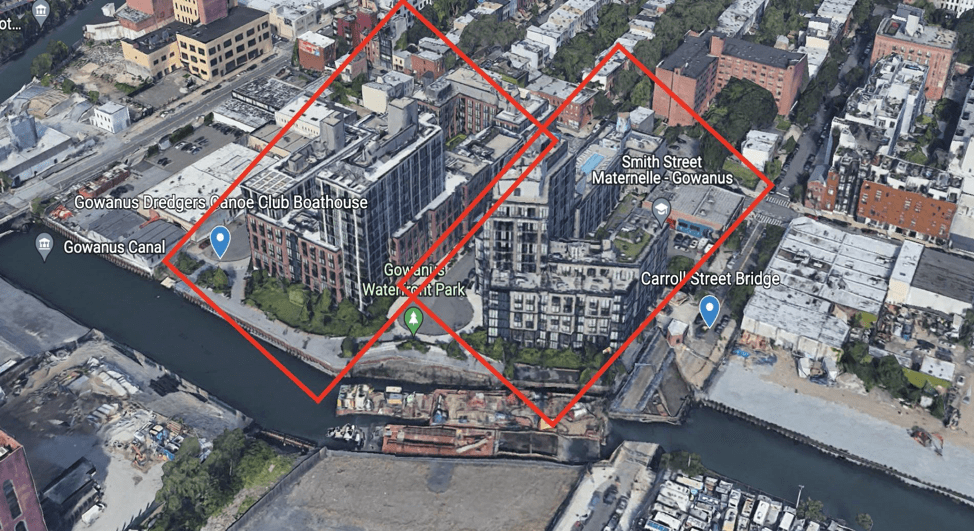

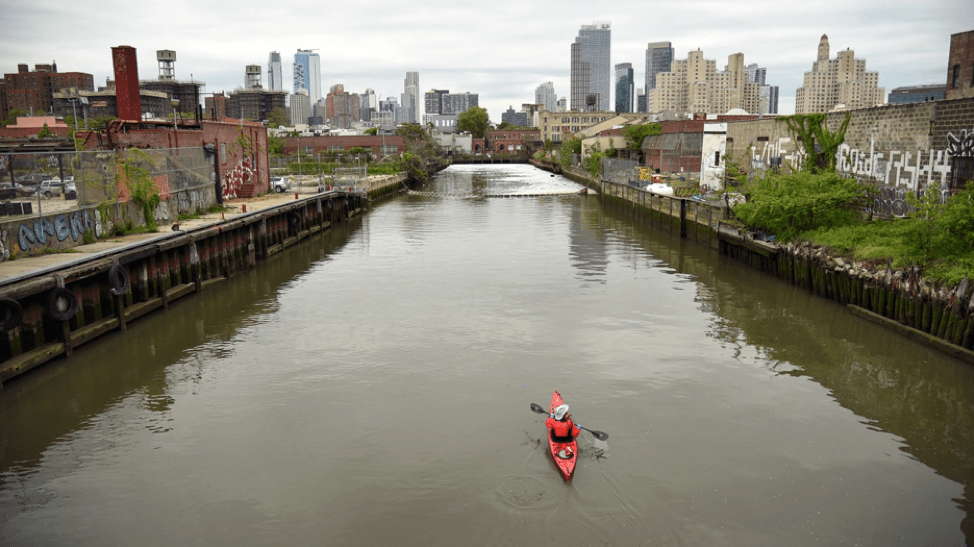

Gowanus Canal*

(adapted from New York Times, Engineering News-Record, Gowanus Canal Conservancy, Environmental Protection Agency EPA, Gowanus Superfund.com, Brownstoner, Wikipedia, City Limits, Southwest Brooklyn Industrial Development Corporation)

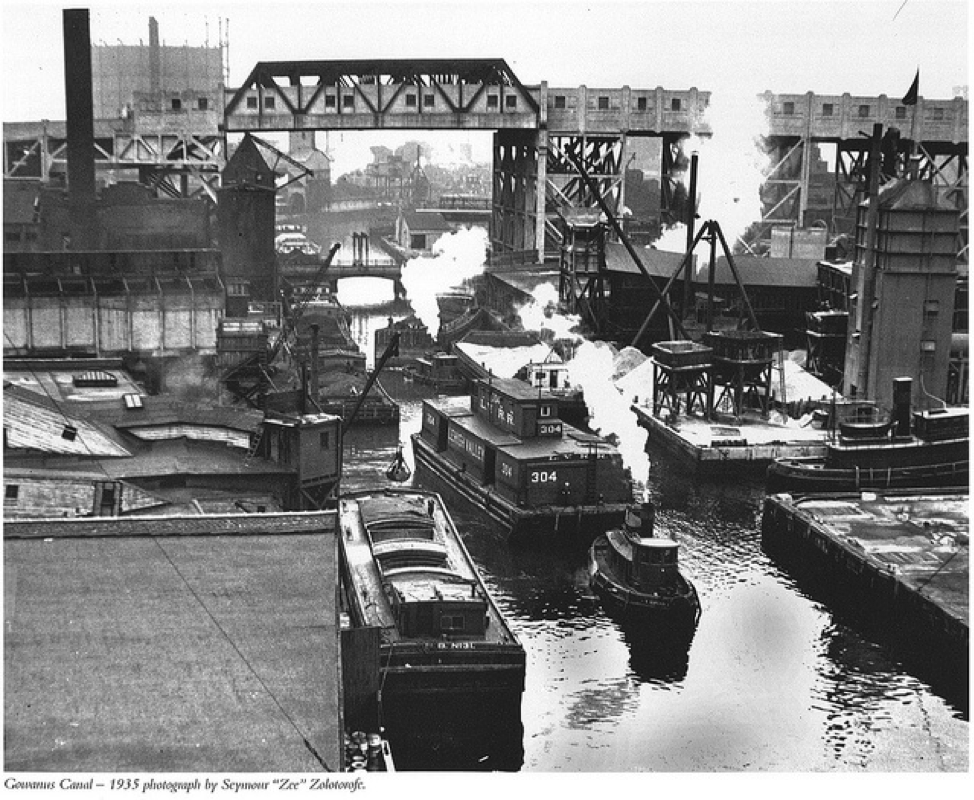

The Gowanus Canal (originally known as the Gowanus Creek) is a 1.8-mile-long canal that was expanded from a marshy tidal creek to become a vital cargo transportation hub in the middle of the 19th century. The area and its creek are thought to be named after a Canarsee chief named Gouwane. Canarsee were a band of Munsee-speaking Lenape who inhabited the westernmost end of Long Island at the time the Dutch colonized New Amsterdam in the 1620s and 1630s. Dutch colonists found the creek to be a pristine tidal inlet bordered with rich salt marshes inhabited by fish and beavers and also, according to legend, foot-long oysters. The Gowanus Creek was widened and its shoreline reinforced to become the Gowanus Canal in 1869. The completed canal extended and connected to Brooklyn’s already very busy maritime and commercial shipping activities. At its busiest, as many as 100 ships a day transported cargo through it.

Manufactured gas plants (MGP), coal yards, paper mills, tanneries, stone yards, soap makers, paint factories, and chemical plants operated along the canal for over 100 years, discharging their unfiltered wastes into its waterways. Overflows from sanitary sewers and stormwater during heavy rain events combined with residual industrial pollutants to create one of the nation’s most contaminated water bodies. The Gowanus Canal was designated an EPA Superfund Site (added to the National Priorities List) in 2010 and remediation work began in November 2020. More than a dozen contaminants, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, polychlorinated biphenyls and heavy metals, including mercury, lead and copper, are found at high levels in the sediment in the canal. To manage the clean-up work, the canal was divided into three “Remediation Target Areas” or RTAs. The first segment runs from the top of the Canal to 3rd Street, the second segment from 3rd Street to just south of the Hamilton Avenue Bridge and the third segment runs from the Hamilton Avenue Bridge to the mouth of the Canal.

The EPA and other organizations track the clean up progress. In November 2021, the New York City Council approved (47-1) a plan to upzone an 82-block swath of Gowanus. With this policy change, Gowanus will gain roughly 8.500 new apartments, or approximately 22,000 new residents. The rezoning plan allows residential towers up to 30 stories-tall near the Gowanus Canal and around 17 stories-tall along 4th Avenue.

The Gowanus upzoning plan was the first to undergo an independent racial impact study, which found that the rezoning would increase income and racial diversity in the neighborhood. The City Council voted to make racial equity reports mandatory for new residential developments. The approved upzoning plan continues to encounter active resistance from neighborhood groups who call out the City for its “intentional willful noncompliance” and overall failure to comply with federal cleanup requirements for the canal. Other concerns include the City’s handling of canal-adjacent toxic legacy sites, managing sewage and stormwater outflows, providing permanent access to the waterways for recreational and educational uses, the loss of the industrial character of the neighborhood, and skepticism about the City’s ability to hold private developers accountable for providing permanently affordable housing.

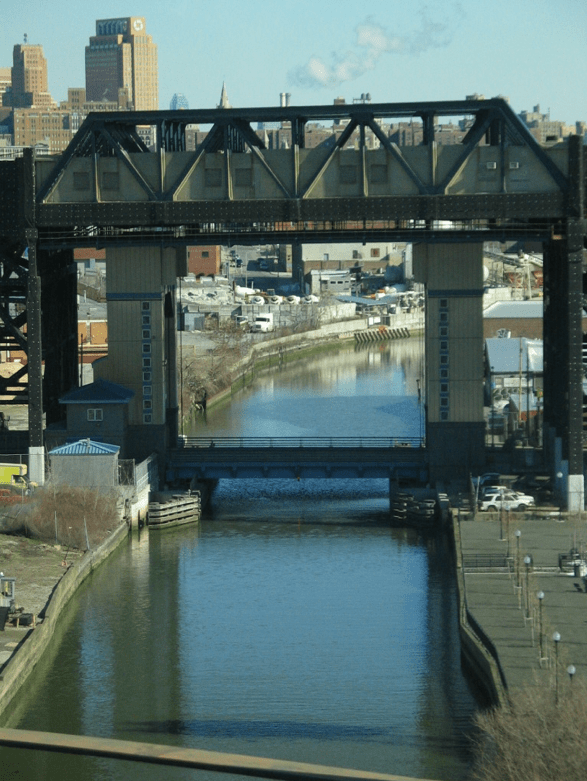

Culver Viaduct*

Culver Viaduct, Smith and Ninth Streets, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from Structure Magazine, Wikipedia, NYC Subway, Urban Omnibus)

Constructed in 1933 as part of the original Culver Line to allow tall-mast ships to pass below it on the Gowanus Canal, the Culver Viaduct remains a crucial part of the New York City rapid transit system. The Viaduct, which spans roughly one mile, supports four tracks, two subway lines (F and G lines), and two stations including, at 87.5 feet, the highest aboveground station in the world, the Smith-Ninth Street stop.

Credit: GK Tramrunner

The present-day line was built as two unconnected segments operated by the Independent Subway System (IND) and Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT). The northern section of the line, which includes the Culver Viaduct, runs primarily underground except for a short elevated section over the Gowanus Canal.

Gowanus Canal Conservancy Lowlands Nursery*

25 9th Street, Brooklyn, NY

Gowanus Canal Conservancy (GCC) serves as an environmental steward for the Gowanus Canal and watershed through its education, outreach, and advocacy efforts. GCC’s Lowlands Nursery grows plants that are well-adapted to the urban conditions of Gowanus, celebrating the local ecosystem while educating and engaging the community in environmental stewardship. GCC leads grassroots volunteer projects, educates students on environmental issues, and, as a convener of disparate voices, works with agencies, elected officials, landowners, ecologists, and community members to advocate for resilient, biodiverse and accessible green infrastructure and public spaces in the Gowanus neighborhood.

St. Mary’s Skate Park

St. Mary’s Skate Park, Smith Street and Nelson Street, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from New York City Parks Department)

This small skate park is tucked under the Culver Viaduct, providing a space for local skaters under the train. The unsupervised concrete park includes elements such as a mini-ramp and flat rail.

Little Free Library

Little Free Library, 208 Luquer Street, Brooklyn, NY

The motto of the Little Free Library, a community-based book exchange project, is “Take a Book. Share a Book.” Keep an eye open for the Little Free Library near St. Mary’s Park as you’re walking by.

Gowanus Dredgers Canoe Club, 165 2nd Street, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from Gowanus Dredgers, Billion Oyster Project)

The Gowanus Dredgers Canoe Club, founded in 1999, is an all-volunteer educational and advocacy organization dedicated to providing waterfront access. Activities are conducted on the canal and neighboring waterfront communities. All of the Gowanus Dredgers facilities, equipment and funding are used for waterfront activation and to expand knowledge about the canals, estuaries, and bays. The Gowanus Dredgers support the Billion Oyster Project. Oyster reefs once covered more than 220,000 acres of the Hudson River estuary, yet today oysters are functionally extinct in New York Harbor as a result of over-harvesting, dredging, and pollution. The absence of oysters has impaired the estuary’s ability to clean the water and absorb excess nitrogen while the loss of reefs has reduced protective habitat, destabilized the sea floor, and left the shoreline vulnerable to destructive wave action. The Billion Oyster Project aims to reverse these effects by bringing oysters and their reef habitat back to New York Harbor. The Gowanus Dredgers conduct a monthly monitoring and tracking of the oysters growth.

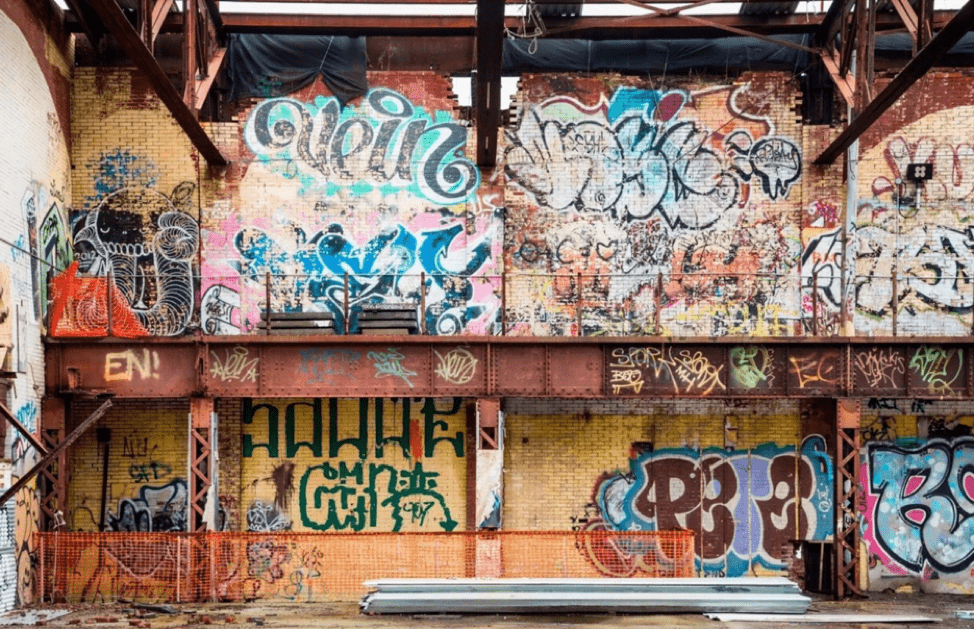

Powerhouse Arts

Powerhouse Arts, 322 3rd Ave, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, Powerhouse Arts, Atlas Obscura by Hannah Frishberg, Six to Celebrate, Wikipedia, Herzog & de Meuron Architects, PBDW Architects)

The former Brooklyn Rapid Transit (BRT) Central Power Station’s Engine House is a monumental link to the Gowanus Canal’s industrial past and a significant structure in the development of mass transit in New York City. It was built in 1901-04 by the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company, which gained a near-monopoly over Brooklyn’s railroad and streetcar lines since being established in 1896. The new power station consolidated generating operations for Brooklyn’s various mass-transit lines on a single site, marking the company’s emergence as one of the country’s largest transit providers and representing an important step towards the creation of an integrated mass-transit system. The BRT Power Station originally consisted of two main blocks: a northern section, demolished prior to 1950, which served as the Boiler House, and the existing south section that included the Engine House, which contained the engine and dynamo room. The Brooklyn Eagle called the facility “one of the largest as well as finest power plants owned by any street railway company in the country.” The Engine House remained in operation, providing power to the Fourth Avenue subway, until 1972 when the site was abandoned. Graffiti artists and homeless people occupied the buildings soon afterwards and renamed the main building the Batcave, or Gowanus Batcave. By the early 2000s the decaying industrial hulk had become home to a large community of teenage runaways, graffiti artists, and musicians.

In 2012, Joshua Rechnitz purchased the property and hired Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron together with New York City architects PBDW to renovate the existing Engine House (also called the Turbine Hall) and to design an addition. Powerhouse Arts includes event and exhibition spaces, studio spaces, and fabrication facilities for artists in different mediums including ceramics and printmaking. In 2019, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the Gowanus Batcave as an official city landmark.

Carroll Street Bridge*

Carroll Street Bridge, between Nevins and Bond Streets, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from New York Times, Forgotten New York, Library of Congress, Wikipedia)

The Carroll Street Bridge, constructed in 1888-89, is the oldest of the four remaining retractile bridges in the United States and is an official New York City landmark. Carroll Street Bridge was built by the Brooklyn Department of City Works and is one of two retractile bridges in New York City; the other one can be found on Borden Avenue crossing Dutch Kills in Hunters Point, Queens.

A retractile bridge slides along a track to allow the bridge to move and ships to pass. Originally, the span was retracted using a steam engine, but today it is powered by an electric motor. Swinging gates on either side close off the span whenever the Carroll Street Bridge is in the open position. An operator’s house is located on the bridge’s western end along the southern sidewalk. The booth is normally unmanned, but a bridge attendant can travel to the operator’s house within two hours in case the bridge needs to be opened. The form is thought to have been invented by T. Willis Pratt in the 1860s.

[RIP] Fulton Municipal Manufactured Gas Plant

Eight parcels along Nevins, Sackett, DeGraw Streets and Gowanus Canal

(adapted from National Grid, NYS Department of Environmental Conservation, Brooklyn Paper)

Gas used for cooking, lighting, heating and commercial purposes was manufactured at the Fulton Municipal Manufactured Gas Plant (MGP) from approximately 1879 through the early 1930s. The plant used coal and petroleum products to create a flammable gas which was piped into the surrounding neighborhoods. The plant occupied several city blocks along Sackett, DeGraw, and Nevins streets, between the Gowanus Canal and 3rd Avenue in Brooklyn. Historical records, while incomplete, indicate that two different companies may have operated the plant before it was sold to Brooklyn Union Gas, a predecessor to National Grid. National Grid is responsible for the investigation and remediation of the site because it was operated by a predecessor company at the time the contamination occurred.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) directs statewide site investigations and remediation plans for former Manufactured Gas Plants (MGPs) and toxic legacy sites. To date, NYSDEC has identified approximately 235 MGP sites requiring remediation across New York State.

Gowanus Canal Flushing Tunnel and Pumping Station*

Gowanus Canal Flushing Tunnel and Pumping Station, 201 Douglass Street (aka 196 Butler Street), Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from Landmarks Preservation Commission, NYC.gov)

Completed in 1911, the Gowanus Flushing Tunnel Pumping Station and Gate House were part of a major infrastructure project intended to cleanse the polluted waters of the Gowanus Canal. At the time of the flushing tunnel’s opening it represented one of the most ambitious efforts ever attempted to clean a polluted American waterway.

The original plan to maintain the water quality in the Gowanus Canal relied on the ebb and flow of the tides, but it was insufficient from the beginning and increasing amounts of waste and sewer runoff from industrial and residential development in the area worsened the already polluted conditions. Brooklyn’s sewer engineers decided in 1904 to construct a mile-long tunnel under Brooklyn’s streets linking the Gowanus Canal with Buttermilk Channel in Upper New York Bay. A nine-foot propeller near the head of the canal would draw dirty water into the tunnel and initiate a constant flushing action that was expected to permanently clean the canal. When construction began, only two similar projects, in Milwaukee and Chicago, had been completed in the United States.

The pumping station opened with much fanfare on June 21, 1911 and continued to provide the vital function of pumping foul water from the canal into Buttermilk Channel until the 1960s when the mechanism failed. The pumping station remained dormant for 30-years until the City’s Department of Environmental Protection reactivated the flushing tunnel in 1999 at which time the flow was reversed in order to bring oxygenated water to the head of the canal. In 2014, the tunnel was again reactivated after a four-year upgrade. Intrepid urban explorers have shared their not-necessarily-sanctioned photos of the tunnels. Today, the Pumping Station and Gate House remain in active use as part of the tunnel system, which pumps more than 250 million gallons of bay water into the Gowanus Canal each day.

Old Stone House

Old Stone House, 336 Third Street, Brooklyn, NY

(adapted from Old Stone House, Dylan Yeats, Ph.D. via Old Stone House, New York Streets, Wikipedia)

The Old Stone House building is a reconstruction of the 1699 Vechte-Cortelyou House on land taken from the Lenape as early as 1639. Located in Washington Park, the current house occupies the site where the original Dutch farmstead stood and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Old Stone House site was once adjacent to the Lenape town of Marechkawick on the banks of the Gowanus Creek. Records indicate that hundreds of Lenape people lived at Marechkawick, growing corn and other crops in the rich soil surrounding the Gowanus.

European settlers began “purchasing” land near the Gowanus from the leaders of Marechkawick and other Lenape towns in 1636. The Vechte family arrived in New Amsterdam from the Netherlands in 1670. Hendrick Claessen Vechte commissioned the Old Stone House in 1699. Hendrick was a wealthy man and served as Justice of the Peace for Brooklyn. His son Nicholas Vechte was born at the Old Stone House in 1704, living at the farm until his death during the Revolutionary War.

Like many of their neighbors, the Vechtes enslaved generations of people of African descent. These enslaved people did most of the work on the Vechte farm–managing the planting and harvesting of grains, vegetables and fruit; gathering and harvesting oysters; raising livestock; cooking, cleaning, and taking care of children in the households.

During the 1880s, the pre-Dodgers Brooklyn baseball team, the Bridegrooms, used Washington Park as a baseball field, and the house consequently became their clubhouse. At some point after the team moved in 1891, the house was destroyed (probably in 1897) and its foundations buried as private developers and city planners made way for new houses. When the Old Stone House’s remains were recovered in the 1930s, efforts to begin reconstruction began.

END OF BIG WALK 2023