Note: We will visit each of the sites titled in red and underlined on the walk and do our best to visit them in the order they appear here. But, to keep on schedule, we will not stop at those sites titled in black. We strongly encourage you to visit those we’ll skip — and, indeed, everything on the list — on your own!

Webster Hall (119-125 E. 11th Street)

While New York City’s Webster Hall is well known today for its claim over today’s popular music performances, the famed venue might have also been the country’s very first LGBTQ club. According to the on-line magazine Milk, Webster Hall hosted the very first gay events back in the 1910s and ’20s. These “events” were the infamous drag balls that were so wild and rambunctious that the city dubbed the venue “Devil’s Playground”. Partygoers were encouraged to arrive in full drag – a concept considered completely novel during a time when the state of New York had actually banned the appearance or even discussion of gay people in public. Read more by clicking here or look at a longer timeline of Webster Hall’s history by clicking here.

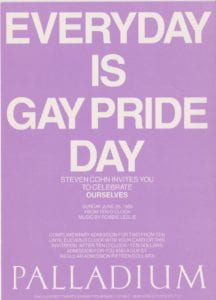

The Palladium (140 E. 14th Street)

Now an NYU dormitory, gym, and career center, The Palladium, as it was once called, first opened in 1927 as a movie palace designed by famous theater architect Thomas White Lamb. (Back then it was called the Academy of Music.) By the early 1970s, it had stopped showing movies and, in 1976, it was reborn as a nightclub. The Rolling Stones, Blue Oyster Cult, the  Grateful Dead, The Clash, Blondie, U2, The Ramones Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band, Frank Zappa, and Lou Reed, among others, played at The Palladium. Some musicians even recorded concerts there. According to Hans Von Rittern, Palladium was also “one of the last great dance palaces of the disco era.” Every Sunday into the late-1990s the venue catered to a predominantly gay clientele. As Von Rittern remembers: “Junior Vasquez’s Arena party, held Saturday nights and all day Sundays at Palladium between September 1996 and September 1997, was one of the most popular parties in the New York club scene at the time. Although the promoters billed Arena as ‘The Gay Man’s Pleasure Dome”, the party drew an eclectic mix of gay and straight from Manhattan and far beyond.” Artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and Kenny Scharf all painted murals in The Palladium -all of which were destroyed when the building was transformed into its current version.

Grateful Dead, The Clash, Blondie, U2, The Ramones Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band, Frank Zappa, and Lou Reed, among others, played at The Palladium. Some musicians even recorded concerts there. According to Hans Von Rittern, Palladium was also “one of the last great dance palaces of the disco era.” Every Sunday into the late-1990s the venue catered to a predominantly gay clientele. As Von Rittern remembers: “Junior Vasquez’s Arena party, held Saturday nights and all day Sundays at Palladium between September 1996 and September 1997, was one of the most popular parties in the New York club scene at the time. Although the promoters billed Arena as ‘The Gay Man’s Pleasure Dome”, the party drew an eclectic mix of gay and straight from Manhattan and far beyond.” Artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and Kenny Scharf all painted murals in The Palladium -all of which were destroyed when the building was transformed into its current version.

St. Mark’s Baths (6 St. Mark’s Place)

As one of the few places gay men could meet and share intimacy well into the 20th century, bathhouses have long been essential to gay culture and sociability. Yet because bathhouses were often associated with homosexuality by police and other “vice investigators,” they were also targets of harassment, raids, and arrests. In 1903, for example, a raid on the Ariston Hotel Baths resulted in the arrest of 26 men, 7 of whom were convicted of sodomy charges and served between 4 and 20 years in prison. It took another 77 years for the New York State Court of Appeals tofinally abolish anti-sodomy laws.

As one of the few places gay men could meet and share intimacy well into the 20th century, bathhouses have long been essential to gay culture and sociability. Yet because bathhouses were often associated with homosexuality by police and other “vice investigators,” they were also targets of harassment, raids, and arrests. In 1903, for example, a raid on the Ariston Hotel Baths resulted in the arrest of 26 men, 7 of whom were convicted of sodomy charges and served between 4 and 20 years in prison. It took another 77 years for the New York State Court of Appeals tofinally abolish anti-sodomy laws.

The St. Mark’s Bathhouse opened in 1906 and served a mixed clientele up until 1979, when its owner, Bruce Mailman announced that it would thereafter serve exclusively gay customers. The baths were beloved for their “chic appeal” in these years, but soon suffered scrutiny as the HIV/AIDS epidemic began to spread throughout the city. In December of 1985, the New York City Department of Health forced Mailman to close the baths. St. Mark’s Baths was one of several such establishments to be closed by the city in 1985 and 1986. Read more about the landmark at this link.

Tompkins Square Park (Between Avenues A and B, E. 7th and E. 10th Streets)

This 10.5 acre park contains so much history, it’s almost impossible to distill it to one genre, moment, or meaning. For queer New Yorkers, the park is particularly significant as the site of Wigstock, first celebrated there in 1984. The web site for the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation notes that, Lady Bunny founded the event and that “Wigstock was an outdoor drag festival held each year on Labor Day to act as the unofficial end of summer for the gay community in New York City. It  began when a group of drag queens from the nearby Pyramid Club performed a spontaneous drag show in the park.” Eventually the celebration moved to Union Square and then to the Hudson River piers. Although it officially ended in 2001, the festival made “guest appearances” as part of the East Village Howl Festival. In 2015 and 2016, there was a Wigstock evening cruise in New York Harbor. In 2018, to everyone’s delight, the festival was revived, this time at Pier 17 on September 1.

began when a group of drag queens from the nearby Pyramid Club performed a spontaneous drag show in the park.” Eventually the celebration moved to Union Square and then to the Hudson River piers. Although it officially ended in 2001, the festival made “guest appearances” as part of the East Village Howl Festival. In 2015 and 2016, there was a Wigstock evening cruise in New York Harbor. In 2018, to everyone’s delight, the festival was revived, this time at Pier 17 on September 1.

STAR House (213 E. 2nd Street)

The STAR House, named for the community activist group Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), was a site for transgender and queer people of color who were often homeless. At STAR House, folks could find a safe place to sleep or enjoy a meal, while receiving peer-to-peer support from community activists such as Sylvia Rivera or Marsha P. Johnson. STAR demanded justice for low incom e, homeless, and incarcerated transgender people of color, many of whom worked in underground economies performing sex work or drug sales. Sylvia and Marsha were longtime friends who wanted to help folks younger than them who were coming out and moving to NYC at the height of the Gay Power movement. STAR was one of the only activist groups at the time supporting community members in jail or detention centers. Their first public action was an occupation at Weinstein Hall at NYU in 1970. Service organizations such as the Ali Forney Center, the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, Queers for Economic Justice and Sylvia’s Place are a testament to the visionary work begun by STAR in the 1970’s. (With thanks to the Whose Streets, Our Streets project, co-founded by another Gallatin graduate, Wesley Flash.)

e, homeless, and incarcerated transgender people of color, many of whom worked in underground economies performing sex work or drug sales. Sylvia and Marsha were longtime friends who wanted to help folks younger than them who were coming out and moving to NYC at the height of the Gay Power movement. STAR was one of the only activist groups at the time supporting community members in jail or detention centers. Their first public action was an occupation at Weinstein Hall at NYU in 1970. Service organizations such as the Ali Forney Center, the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, Queers for Economic Justice and Sylvia’s Place are a testament to the visionary work begun by STAR in the 1970’s. (With thanks to the Whose Streets, Our Streets project, co-founded by another Gallatin graduate, Wesley Flash.)

Bluestockings Bookstore (172 Allen Street)

Bluestockings is a volunteer-powered and collectively-owned radical bookstore, fair trade cafe, and activist center in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. It seeks to embody and share the principles of intersectional trans-affirming feminisms and support liberatory social movements.The store carries over 6,000 titles on topics such as feminism, queer and gender studies, global capitalism, climate & environment, political theory, police and prisons, race and black studies, radical education, plus many more! You can also find some good ‘ole smutty fiction, sci-fi, and poetry. The store also car ry magazines, zines, journals, alternative menstrual products and other oddly hard-to-find good things. Everyone entering Bluestockings Bookstore is asked to be aware of their language and behavior, and to think about whether it might be harmful to others. The store defines oppressive behavior as any conduct that demeans, marginalizes, rejects, threatens or harms anyone on the basis of ability, activist experience, age, cultural background, education, ethnicity, gender, immigration status, language, nationality, physical appearance, race, religion, self-expression, sexual orientation, species, status as a parent or other such factors. Bluestockings is named after The Blue Stockings Society, a mid-18th century English political movement and literary discussion group to promote female authorship and readership.

ry magazines, zines, journals, alternative menstrual products and other oddly hard-to-find good things. Everyone entering Bluestockings Bookstore is asked to be aware of their language and behavior, and to think about whether it might be harmful to others. The store defines oppressive behavior as any conduct that demeans, marginalizes, rejects, threatens or harms anyone on the basis of ability, activist experience, age, cultural background, education, ethnicity, gender, immigration status, language, nationality, physical appearance, race, religion, self-expression, sexual orientation, species, status as a parent or other such factors. Bluestockings is named after The Blue Stockings Society, a mid-18th century English political movement and literary discussion group to promote female authorship and readership.

The Loft/The Vault at Pfaff’s (647 Broadway)

From Stephanie Michelle Blalock’s 2011 dissertation, “Walt Whitman at Pfaff’s Beer Cellar: America’s Bohemian poet and the contexts of Calmus”: “Even though Whitman’s notebooks list several New York restaurants and drinking establishments he patronized, his favorite haunt during the antebellum years was Pfaff’s, a popular nightspot at No. 647 Broadway. In an interview printed in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in July 1886, Whitman recalled, “I used to go to Pfaff’s nearly every night . . . It used to be a pleasant place to go in the evening.” Here, Whitman not only asserts that Pfaff’s functioned like a European salon, offering its patrons a forum for lively debates, but he also implies that it served as an American saloon, a popular hangout and drinking establishment or, as another customer put it, the “preferred trysting place” of a vibrant if eccentric clientele. Whitman’s fond memories of going to Pfaff’s every night and taking his place at a table positioned directly beneath the sidewalks of Broadway reveals that the poet saw himself, quite literally, as part of a significant underground network of Pfaff’s patrons during the late antebellum period and the first year and a half of the Civil War. The poet’s presence at Pfaff’s and his participation in its vibrant social scene spanned at least three years. It is difficult to determine precisely when Whitman first discovered the beer cellar; he likely sought comrades among its regulars, including off-duty doctors and medical students in addition to the bohemian crowd, before the winter of 1859.”

From Stephanie Michelle Blalock’s 2011 dissertation, “Walt Whitman at Pfaff’s Beer Cellar: America’s Bohemian poet and the contexts of Calmus”: “Even though Whitman’s notebooks list several New York restaurants and drinking establishments he patronized, his favorite haunt during the antebellum years was Pfaff’s, a popular nightspot at No. 647 Broadway. In an interview printed in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in July 1886, Whitman recalled, “I used to go to Pfaff’s nearly every night . . . It used to be a pleasant place to go in the evening.” Here, Whitman not only asserts that Pfaff’s functioned like a European salon, offering its patrons a forum for lively debates, but he also implies that it served as an American saloon, a popular hangout and drinking establishment or, as another customer put it, the “preferred trysting place” of a vibrant if eccentric clientele. Whitman’s fond memories of going to Pfaff’s every night and taking his place at a table positioned directly beneath the sidewalks of Broadway reveals that the poet saw himself, quite literally, as part of a significant underground network of Pfaff’s patrons during the late antebellum period and the first year and a half of the Civil War. The poet’s presence at Pfaff’s and his participation in its vibrant social scene spanned at least three years. It is difficult to determine precisely when Whitman first discovered the beer cellar; he likely sought comrades among its regulars, including off-duty doctors and medical students in addition to the bohemian crowd, before the winter of 1859.”

The Slide/Portofino (157 Bleecker Street & 206 Thompson Street)

The Slide and Portofino restaurant are an unlikely match for their significance to New York’s queer history, but they are so near one another, it’s difficult not to discuss them together. The Slide was a popular 1890s bar where those looking for thrills and entertainment might find common cause with other patrons. It was also known to police, who closed it in 1892, as a prime location for “fairies,” or men seeking sexual liaisons with other men. Portofino restaurant stood nearby on Thompson Street from 1859 to 1975. Famous as a “discreet meeting place frequented on Friday evenings by lesbians.” The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation offers more context: “The 2013 groundbreaking Supreme Court decision that overturned the federal Defense of Marriage Act had its roots here in the 1963 meeting of Edith S. Windsor and Thea Clara Spyer. Edith “Edie” Windsor was born in Philadelphia in 1929 to a Russian Jewish immigrant family. She graduated from Temple University and later moved to New York City to pursue a master’s degree in mathematics at New York University. She eventually became one of the first female senior systems programmers at IBM. Thea Clara Spyer was born in Amsterdam in 1931 to a Jewish family that fled to the U.S. to escape the Holocaust before the Nazi invasion of the Netherlands. She was expelled from Sarah Lawrence College after a guard caught her kissing another woman, but later received her bachelor’s degree from the New School for Social Research, and a master’s degree and PhD in clinical psychology from the City University of New York and Adelphi University, respectively. Windsor and Spyer began dating after meeting at Portofino in 1963…The couple married in Canada in 2007 after that country legalized same-sex marriage, and when Spyer died in 2009, she left her entire estate to Windsor. Windsor sued to have her marriage recognized in the U.S. after receiving a large tax bill from the inheritance, seeking to claim the federal estate tax exemption for surviving spouses…United States v. Windsor was a landmark civil rights ruling which came down on June 26, 2013 in which the Supreme Court held that restricting U.S. federal interpretation of “marriage” and “spouse” to apply only to opposite-sex unions is unconstitutional. It helped lead to the legalization of gay marriage in the U.S.”

The Slide and Portofino restaurant are an unlikely match for their significance to New York’s queer history, but they are so near one another, it’s difficult not to discuss them together. The Slide was a popular 1890s bar where those looking for thrills and entertainment might find common cause with other patrons. It was also known to police, who closed it in 1892, as a prime location for “fairies,” or men seeking sexual liaisons with other men. Portofino restaurant stood nearby on Thompson Street from 1859 to 1975. Famous as a “discreet meeting place frequented on Friday evenings by lesbians.” The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation offers more context: “The 2013 groundbreaking Supreme Court decision that overturned the federal Defense of Marriage Act had its roots here in the 1963 meeting of Edith S. Windsor and Thea Clara Spyer. Edith “Edie” Windsor was born in Philadelphia in 1929 to a Russian Jewish immigrant family. She graduated from Temple University and later moved to New York City to pursue a master’s degree in mathematics at New York University. She eventually became one of the first female senior systems programmers at IBM. Thea Clara Spyer was born in Amsterdam in 1931 to a Jewish family that fled to the U.S. to escape the Holocaust before the Nazi invasion of the Netherlands. She was expelled from Sarah Lawrence College after a guard caught her kissing another woman, but later received her bachelor’s degree from the New School for Social Research, and a master’s degree and PhD in clinical psychology from the City University of New York and Adelphi University, respectively. Windsor and Spyer began dating after meeting at Portofino in 1963…The couple married in Canada in 2007 after that country legalized same-sex marriage, and when Spyer died in 2009, she left her entire estate to Windsor. Windsor sued to have her marriage recognized in the U.S. after receiving a large tax bill from the inheritance, seeking to claim the federal estate tax exemption for surviving spouses…United States v. Windsor was a landmark civil rights ruling which came down on June 26, 2013 in which the Supreme Court held that restricting U.S. federal interpretation of “marriage” and “spouse” to apply only to opposite-sex unions is unconstitutional. It helped lead to the legalization of gay marriage in the U.S.”

Washington Square Park

Washington Square Park has long been a site for queer activists to convene, protest, talk, and be heard. The park has been the official and unofficial end-point of the annual Pride Parade and Dyke March in New York, and it has also served as the centerpiece of a neighborhood that has served the queer community through a variety of services and celebrations. Among the institutions lining the park that have been critical to queer life here are Judson Memorial Church, Gay Men’s Health Crisis (founded at 2 Fifth Avenue), and the former Washington Square Episcopal Methodist Church on West 4th Street, which has been converted to luxury condos.

Washington Square Park has long been a site for queer activists to convene, protest, talk, and be heard. The park has been the official and unofficial end-point of the annual Pride Parade and Dyke March in New York, and it has also served as the centerpiece of a neighborhood that has served the queer community through a variety of services and celebrations. Among the institutions lining the park that have been critical to queer life here are Judson Memorial Church, Gay Men’s Health Crisis (founded at 2 Fifth Avenue), and the former Washington Square Episcopal Methodist Church on West 4th Street, which has been converted to luxury condos.

Please watch this short, 5 minute video of trans activist Sylvia Rivera speaking under the Washington Square Arch after the first NYC Pride Parade in 1973. (Click on the image of Rivera to launch Vimeo and watch.)

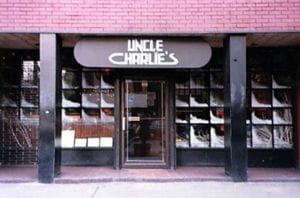

Uncle Charlie’s Downtown (56 Greenwich Avenue)

From Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York: “Uncle Charlie’s Downtown opened in the early 1980s in Greenwich Village, part of a popular chain of gay bars in New York City. Born at the same time as MTV, it was one of the first video bars, and soon earned a reputation as a place where nobody spoke, but just stood and watched, a so-called “S&M” bar, for Stand and Model. During the AIDS crisis,  Uncle Charlie’s Downtown became one of the most popular gay bars of the 1980s with one of the busiest happy hours, packing them in with screenings of Dynasty Wednesdays & Golden Girl Saturdays. Maybe people needed something light during that time of tragedy….In 1997, Uncle Charlie’s was forced to close its doors, ending an era in Greenwich Village gay history. The reason? A drop in customers as Chelsea was gaining popularity as the “new” destination for gay men, along with a 50 percent increase in rent.”

Uncle Charlie’s Downtown became one of the most popular gay bars of the 1980s with one of the busiest happy hours, packing them in with screenings of Dynasty Wednesdays & Golden Girl Saturdays. Maybe people needed something light during that time of tragedy….In 1997, Uncle Charlie’s was forced to close its doors, ending an era in Greenwich Village gay history. The reason? A drop in customers as Chelsea was gaining popularity as the “new” destination for gay men, along with a 50 percent increase in rent.”

The LGBT Center (208 W. 13th Street)

The Center has been a home and resource hub for the LGBT community, NYC residents and visitors since its found ing in 1983. The Center is a place to connect and engage, find camaraderie and support, and celebrate the vibrancy and growth of the LGBT community. Among many of its offerings are arts and cultural programs, health counseling and support, family activities, mentorship, youth leadership opportunities, career services, and a tremendous archive of LGBT history. Highlights of the building include a Keith Haring-designed restroom, conference and community space, a coffee shop serving Think Coffee, and the Pat Parker/Vito Russo Library. In 2016, The Center became the first LGBT specific space to be featured on Google Cultural Institute. Read more about the Center at their web site: https://gaycenter.org/ And read more about the space, including the Keith Haring restroom at the Google Arts and Culture App, accessible by clicking on this link: https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/nwJihaZPJxtSIg

ing in 1983. The Center is a place to connect and engage, find camaraderie and support, and celebrate the vibrancy and growth of the LGBT community. Among many of its offerings are arts and cultural programs, health counseling and support, family activities, mentorship, youth leadership opportunities, career services, and a tremendous archive of LGBT history. Highlights of the building include a Keith Haring-designed restroom, conference and community space, a coffee shop serving Think Coffee, and the Pat Parker/Vito Russo Library. In 2016, The Center became the first LGBT specific space to be featured on Google Cultural Institute. Read more about the Center at their web site: https://gaycenter.org/ And read more about the space, including the Keith Haring restroom at the Google Arts and Culture App, accessible by clicking on this link: https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/nwJihaZPJxtSIg

AIDS Memorial Park/St. Vincent’s (200-218 W. 12th Street)

In his statement designating the St. Vincent’s triangle as AIDS Memorial Park, NYC Parks Commissioner Mitchell J. Silver declared, “The New York City AIDS Memorial Park at St. Vincent’s Triangle stands at the crossroads of the richly historical West Village. Here, we honor and celebrate St. Vincent’s Hospital’s more than 150 years of service to our city, as well as the countless New Yorkers impacted by AIDS: those we have lost, those who live with H.I.V./AIDS, and those who continue to battle against fear and ignorance.” Studio ai, led by Mateo Paiva, Lily Lim and Esteban Erlich, designed the park’s memorial, which features an 18-foot steel canopy as the dramatic gateway to the new St. Vincent’s Hospital Park in the West Village. It also includes he work of visual artist Jenny Holzer and granite pavers engraved with excerpts from Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself. Read more at: https://nycaidsmemorial.org/.

In his statement designating the St. Vincent’s triangle as AIDS Memorial Park, NYC Parks Commissioner Mitchell J. Silver declared, “The New York City AIDS Memorial Park at St. Vincent’s Triangle stands at the crossroads of the richly historical West Village. Here, we honor and celebrate St. Vincent’s Hospital’s more than 150 years of service to our city, as well as the countless New Yorkers impacted by AIDS: those we have lost, those who live with H.I.V./AIDS, and those who continue to battle against fear and ignorance.” Studio ai, led by Mateo Paiva, Lily Lim and Esteban Erlich, designed the park’s memorial, which features an 18-foot steel canopy as the dramatic gateway to the new St. Vincent’s Hospital Park in the West Village. It also includes he work of visual artist Jenny Holzer and granite pavers engraved with excerpts from Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself. Read more at: https://nycaidsmemorial.org/.

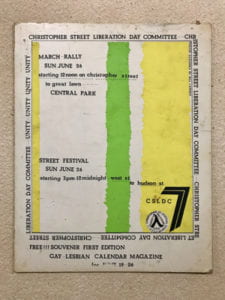

Christopher Street (between West Street and 7th Avenue)

From THUMP magazine: “Even in a geographical sense, Christopher Street has always been a place of disruption. The thoroughfare cuts diagonally through the historic Greenwich Village, which is itself one of the few neighborhoods in Manhattan that doesn’t pay mind to the city’s rigid grid system. Over the course of the early 20th century, it was a safe haven for New York’s LGBTQ community and home to events—including the Stonewall Inn protests—that would become flash points for the mainstreaming of the gay rights movement all across the country.”

From THUMP magazine: “Even in a geographical sense, Christopher Street has always been a place of disruption. The thoroughfare cuts diagonally through the historic Greenwich Village, which is itself one of the few neighborhoods in Manhattan that doesn’t pay mind to the city’s rigid grid system. Over the course of the early 20th century, it was a safe haven for New York’s LGBTQ community and home to events—including the Stonewall Inn protests—that would become flash points for the mainstreaming of the gay rights movement all across the country.”

Stonewall National Monument (53 Christopher Street)

From the National Park Service: “The Stonewall Inn, a bar located in Greenwich Village, New York City, was the scene of an uprising against police repression that led to a key turning point in the struggle for the civil rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) Americans. In a pattern of harassment of LGBT establishments, the New York City police raided the Stonewall Inn in the early hours of Saturday, June 28, 1969. The reaction of the bar’s patrons and neighborhood residents that assembled in the street was not typical of these kinds of raids. Instead of dispersing, the crowd became increasingly angry and began chanting and throwing objects as the police arrested the bar’s employees and patrons. Reinforcements were called in by the police, and for several hours they tried to clear the streets while the crowd fought back. The initial raid and the riot that ensued led to six days of demonstrations and conflicts with law enforcement outside the bar, in nearby Christopher Park, and along neighboring streets. At its peak, the crowds included several thousand people… Stonewall is now regarded by many as the single most important catalyst for the dramatic expansion of the LGBT civil rights movement.” The Stonewall National Monument marks this important turning point and the site of the uprising is recognized by the National Park Service as a National Historic Landmark.

From the National Park Service: “The Stonewall Inn, a bar located in Greenwich Village, New York City, was the scene of an uprising against police repression that led to a key turning point in the struggle for the civil rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) Americans. In a pattern of harassment of LGBT establishments, the New York City police raided the Stonewall Inn in the early hours of Saturday, June 28, 1969. The reaction of the bar’s patrons and neighborhood residents that assembled in the street was not typical of these kinds of raids. Instead of dispersing, the crowd became increasingly angry and began chanting and throwing objects as the police arrested the bar’s employees and patrons. Reinforcements were called in by the police, and for several hours they tried to clear the streets while the crowd fought back. The initial raid and the riot that ensued led to six days of demonstrations and conflicts with law enforcement outside the bar, in nearby Christopher Park, and along neighboring streets. At its peak, the crowds included several thousand people… Stonewall is now regarded by many as the single most important catalyst for the dramatic expansion of the LGBT civil rights movement.” The Stonewall National Monument marks this important turning point and the site of the uprising is recognized by the National Park Service as a National Historic Landmark.

Julius’ (159 W. 10th)

From the Julius’ web site: “Julius’ is a bar that has a lot of history. This structure has been welcoming folks since 1840, first as a grocery store and then, in 1864 as a bar. It was built in 1826 on the corner of Amos Street (West 10th) and Factory Street (Waverly Place). During Prohibition (1020-1933), the bar was a popular speakeasy and, along with Nick’s at the corner of Seventh Avenue South and the nearby Village Vanguard, was frequented by many of the jazz and literary legends of the era. It started to attract a gay clientele in the 1950s and some suggest it is the oldest gay bar in the city and the oldest bar in the village. On April 21, 1966, four ‘homophile’ [a word embraced by gay and lesbian civil rights activists in the 1960s and 1970s] activists staged a “sip in” at Julius’ to challenge the NYS Liquor Authority’s regulation that prohibited bars and restaurants from serving homosexuals. Accompanied by five reporters, the group visited a number of bars until they were denied service at Julius’, a longtime Greenwich Village gay bar. The incident drew a denial from the SLA chairman that his agency told bars not to serve homosexuals and precipitated an investigation by the chairman of the city’s Human Right’s Commission.”