By Jack Bobley*

The Neues Kreuzberger Zentrum stands as a striking edifice that captures immediate attention upon emerging from the Kottbusser Tor U-Bahn station. This colossal bright-yellow structure houses over 300 units, forming a horseshoe shape around the central plaza and extending boldly over Adalbertstraße, facilitating traffic with a two-lane underpass. Satellite dishes adorn balconies, and graffiti adorns seemingly inaccessible spots, adding to its unique character. Rising ten stories above ground for residences, with a two-story base housing cafes and shops, the NKZ dominates the skyline, impossible to overlook.

Within the plaza, a vibrant mix of produce stands, takeout joints, bars, art galleries, offices, and even a casino intertwine with the NKZ, creating a bustling microcosm of the multicultural essence of Kotti, the affectionate moniker for the area around Kottbusser Tor. The complex’s integration into the urban landscape is remarkable, with pedestrian underpasses, staircases, and balconies revealing more businesses at every turn. What strikes me most about this scene is that the defining landmark, the architectural marvel of the neighborhood, is a public housing project.

Hailing from the United States, particularly Washington D.C., I’m accustomed to seeing section 8 housing characterized by architectural uniformity, widespread dilapidation, and isolation from amenities and storefronts. Anecdotally, identifying public housing developments in the States is often straightforward due to their detached nature. There’s typically little reason to traverse near or through such developments unless they’re your intended destination. However, the NKZ defies these expectations, albeit not without its own complexities and challenges.

Strolling along the elevated walkway leading to the entrances of some NKZ units, I encountered a juxtaposition of establishments: a police station, a café, a publishing office, and a curtained glass door marked with a “no tourist zone” sticker. Adjacent to the police station, a defiant tag proclaimed “F*** THE POLICE,” while signs outside the café urged patrons to maintain quiet for the residents above. A woman, her gaze icy, rolled a cigarette behind the café’s long glass window. As I reached the walkway’s end, I discovered a table nestled into the stairway banister, accompanied by two chairs overlooking the plaza. While seemingly mundane to some, the presence of such permanent infrastructure designed solely for leisure struck me as remarkable.

For those accustomed to this arrangement, the coexistence of storefronts and offices alongside public housing might not seem noteworthy. However, to my eyes, this simple design philosophy was incredible. Even on that chilly December afternoon, the area bustled with activity: shoppers browsing for produce and fish, commuters heading to the nearby U-Bahn stop, and individuals simply enjoying food and drink. While seemingly ordinary, I was captivated by the stark absence of segregation between residential and commercial activities—a privilege typically reserved for the affluent in the States.

“Kriminalitätsbelasteter Ort”

Yet, despite the NKZ’s successful urban integration, potential issues loomed. Broken bottles littered many corners, and the concentration of homeless individuals seemed higher than in other Berlin neighborhoods. While Kotti appeared relatively clean by American standards, compared to other areas and public housing complexes, the NKZ lacked maintenance. Additionally, the intricate maze-like structure intertwining residential units with storefronts, while architecturally fascinating, created dimly lit pockets obscured from the bustling plaza. These concealed areas, overlooked in urban design, posed safety concerns, particularly for women and minority groups vulnerable to targeted violence, and allegedly served as prime locations for illicit activities like drug deals.

Anecdotally, the general consensus regarding the NKZ is that it’s a “concrete eyesore and a focal point of the local drug trade” (Verlaan, 2020). I stand firmly in the minority as a fan of the NKZ’s use of bright yellow concrete and unusual commercial verticality, but the allegations of the NKZ as a crime hotspot are more difficult to overcome. In 2021, the police documented 2,309 crimes in Kotti according to the Berliner Zeitung. Of these 264 were “cases of minor or serious bodily harm” (Time.news, 2022), 455 were instances of pickpocketing, and a staggering 758 were drug offenses, although this source does not distinguish between possession, small, or large-scale trafficking charges. These numbers are abnormally high for an area of this size in Berlin; however, they do not tell the entire story and should be taken with a grain of salt for a variety of reasons.

Anecdotally, the general consensus regarding the NKZ is that it’s a “concrete eyesore and a focal point of the local drug trade” (Verlaan, 2020). I stand firmly in the minority as a fan of the NKZ’s use of bright yellow concrete and unusual commercial verticality, but the allegations of the NKZ as a crime hotspot are more difficult to overcome. In 2021, the police documented 2,309 crimes in Kotti according to the Berliner Zeitung. Of these 264 were “cases of minor or serious bodily harm” (Time.news, 2022), 455 were instances of pickpocketing, and a staggering 758 were drug offenses, although this source does not distinguish between possession, small, or large-scale trafficking charges. These numbers are abnormally high for an area of this size in Berlin; however, they do not tell the entire story and should be taken with a grain of salt for a variety of reasons.

Kotti is a notoriously over-policed area, with a now even increased law enforcement presence following the opening of a police station built into the NKZ itself in February of 2023. The area surrounding Kottbusser Tor is a government designated “kriminalitätsbelasteter Ort”, or crime-ridden-place. In these government sanctioned zones the police have the authority to stop and search anybody at any time at their own discretion.

In a kriminalitätsbelastetem Ort made up of 70%+ people of immigrant origin, it is not unreasonable to assume skewed documentation of crime due to institutional racism and discrimination on the part of Berlin Police. Put simply: it is in the inherently and systemically racist interest of Berlin Police officers to search residents of ethnic minorities at disproportionately high rates, and accordingly the crime rates of these areas will skyrocket to inaccurate levels. Additionally, it is in the same racist and xenophobic interest of the police to not disclose specific breakdowns of categories of crime, particularly with broad items such as “drug offenses.” A random frisk yielding possession of Gras is itemized identically to a frisk yielding possession of opioids in quantities demonstrating intent to sell. This stigmatization of kriminalitätsbelastete Orte incentivizes more police presence and in turn enables additional funding, evident with the opening of the locally protested NKZ police station opened in 2023 that cost over 3.75 million euros, the same one I passed on my stroll over the elevated walkway. Protests organized by local activist group Kotti für Alle highlight how this massive amount of funding could have instead been put towards social infrastructure helping Kotti to become “a place where everyone can live together without fear” (Exberliner, 2022). Among the ideas proposed by the collective were public toilets, a community meeting center, a supervised injection site or a daycare, but the protests were ultimately unsuccessful and the station now overlooks Adalbertstraße.

There undoubtedly is a disproportionate level of crime surrounding the NKZ, however these levels are exaggerated, and more importantly, are brought upon by a vicious cycle of unjust policing and lack of socioeconomic resources in the area. The criminalization of both possession and distribution of drugs inherently leads to increased levels of violence due to there being no legal avenues of accountability for the dealing or purchasing party; violence and intimidation are some of the only reliable responses to disputes that may arise. This universal truth is felt exponentially more in kriminalitätsbelastete Orte where superfluous amounts of people are charged or incarcerated for acts they may not have been caught committing in wealthier and “safer” areas. This disproportionate level of incarceration leads to more familial and community level economic despair, incentivizing more folks to turn to the distribution of illicit substances to support themselves, and the cycle continues. “People prefer to solve their own problems because nobody here believes the police will help,” says an anonymous resident of the NKZ (Exberliner, 2022). Particularly in majority immigrant areas such as Kotti this cycle and the police’s role within it is implicitly understood, and integration of 24/7 police presence into The NKZ only heightens this tension and deepens its effects.

From “Mietskasernen” to Social Housing

From industrialization in the 1860’s through the end of the second world war Germany was dominated by Mietskasernen, multi-story tenements densely housing massive amounts of workers in unreasonable living conditions. Even compared to other industrial and metropolitan European cities at the time, the density of tenants per building lot was abnormally high. While Paris averaged 20 residents per lot and London just eight, the Berlin Mietskasernen typically had between 45 and 60 (Verlaan, 2020). Many of the workers housed in these tenements were employed at small factories and shops within the inner courtyards of the developments; consequently, noise pollution and stench was a constant. The majority of tenants did not have private toilets, and a distinct lack of sunlight and air circulation had become standardized in these massive and unethical housing developments. These poor living conditions coincident with the destruction of Germany caused by World War II was more than enough to justify extreme urban renewal once the government had sufficient funds to commit to more ambitious urban planning projects in the 1960’s.

While creating housing to replace the estimated 600,000 apartments that were destroyed in the war (Robinson, 2020) was a major factor in the revitalization of Germany’s problematic Gründerzeit buildings, Verlaan raises the point that by the 1960’s this was no longer the sole and primary motivator for urban planners. Following the immediate aftermath of the war and through the 1950’s, the German government was in a state of disaster recovery and sought to create as many apartments as possible. But through the 1950’s the German economy began to stabilize, seeing massive booms in average wages, GDP and employment. More funds were funneled into the government’s housing budget, and a “golden age” of urban planning began to form by the turn of the decade as planners had the money and autonomy to commit to larger scale housing projects.

The power of urban planning was not entirely in the hands of the state, or free from profit incentive, however. Private developers’ input was commonplace in the planning of housing, both government- subsidized and market priced. The Berlinhilfegesetz, or Berlin Funding Law, also was a key factor in this complication. The law stated that private investors could write off 20% of the construction loans and reclaim 30% of their investment costs. This morally-questionable law enabled citizens to donate their own funds to government projects and reap tax benefits for decades to come, and it turned urban renewal into a lucrative and exploitable business that clouded the motivations of many larger scale housing developments. The Neues Kreuzberger Zentrum arguably was one of these projects whose first and foremost goal was one of profit maximization over creation of ethical living conditions. Over a quarter of public housing developments between the end of World War II and 1960 had the fingerprints of private housing development on them in one way or another, and many public officials became intimately involved with these private construction companies. It is speculated that this corruption played a role in many of the more problematic and controversial housing developments from this period, the NKZ allegedly among them, although there is no proof of any malpractice with the NKZ specifically.

A new and controversial architectural design

The NKZ was designed by architect Johannes Uhl, arranged by real estate agent Günther Schmidt and financed by infamous Berlin contractor Heinz Mosch. Mosch’s construction company had already developed properties across Berlin valued at hundreds of millions of Deutsche Marks, and a third of these properties were in prime-for-redevelopment Kreuzberg. In 1963 the Senate designated the plaza surrounding Kottbusser Tor as the future center of commerce for Kreuzberg, and as such Mosch set his sights on the area hoping to capitalize on the Berlinhilfegesetz. Existing landlords knew of the Senate’s designation and withheld selling their property until Mosch offered three to five times the value of similar plots in other neighborhoods, which was easily attainable for the massively successful contractor. The team planned for approximately half of the funding to be garnered privately, and in 1970 they presented their plans for the NKZ in all of its dense, vertical glory.

Important to note is that the development’s 12 stories and 300 housing units were not solely for purposes of density, but the building’s massive chassis was intended to be a physical barrier to block the noise that would emerge from the highway junction planned for right behind the building, although this highway was never constructed largely thanks to the Berlin squatters movement. The reunification of Berlin was a necessary prerequisite to the construction of this highway, and despite that goal seeming distant at the time, Mosch and his team intended for their building and associated profits to be tenable in the long term.

What is fascinating about these early stages of development of the NKZ is the public and (often government run) media’s initial reception to this marriage of privately and publicly funded urban renewal. Mosch had successfully arranged the lumber, or in this case planned the tons of yellow concrete, necessary to ignite the flame of economic development in Kotti. And while in retrospect it appears that his motivations were largely his own personal financial interests, at the time the general reception was that by committing these private funds to aid this massive construction project, he was “committing himself to Kreuzberg” (Kreuzberger Echo, 1968). For some time he had the media and general public of Kreuzberg convinced that this entanglement of private funds was in the residents’ best interests, but the rise of citizen-run journalism raised the glaring conflict-of-interest issues associated with the massive project’s conception.

The community newspaper Kreuzberger Stadtteilzeitung made their stance abundantly clear in their debut 1970 issue: “Renewal does not mean serving the needs of the working classes by offering healthy and humane living conditions—it means profit-making by house owners and landlords” (Kreuzberger Stadtteilzeitung, 1970). The nickname Profitwurm poking fun at the complex’s snake-like design and morally questionable financial practices began to catch on, and protests around Kottbusser Tor soon ensued. While Mosch and his team before had been intimately engaged with the government, their political goodwill was fleeting amid the backlash. During the fallout of them paying in some cases quintuple the market value for the lots necessary to construct the NKZ, the government temporarily withdrew their funding for the project. The team was publicly condemned by government figures including Borough Mayor Günther Abendroth for using taxpayer money to seek out personal financial benefit. Due to their garnering of private investors however, this condemnation and pulling of funds did not stop the demolition process for the NKZ’s lot.

Real estate bonanza

Real estate agent Günther Schmidt faced significant backlash, particularly due to his harsh eviction tactics aimed at removing current tenants from buildings marked for demolition. His crew’s actions, such as removing windows and doors from uncooperative residences, intensified the controversy. Schmidt’s tactics often met resistance, with young socialists swiftly repairing the damage inflicted by his crew, thereby fueling the rapidly growing Berlin squatters movement (Verlaan, 2020). Notably, the popular German squatter band Ton Steine Scherben directly called out Schmidt and Mosch by name in the chorus of their 1972 protest anthem “Rauch-Haus-Song.”

“Das ist unser Haus, schmeißt doch endlich/Schmidt und Press und Mosch aus Kreuzberg raus”

“This is our house, finally throw/Schmidt and Press and Mosch out of Kreuzberg” (Rio Reiser, 1972)

By the spring of 1972, the Senate revised its plan for the NKZ in response to the protests. As part of this revision, a portion of the construction was assigned to a public housing corporation. Most notably, the NKZ would now exclusively consist of social housing units. All parties reached an agreement, and construction commenced. By 1974, the first residents moved in. The construction proceeded at a remarkable pace, likely driven by Schmidt and his team’s desire to secure public subsidies available upon the building’s completion as per the Berlinhilfegesetz. However, the rushed construction resulted in a site with questionable structural integrity at best, reflecting the dangerously rapid assembly time. Furthermore, elements of the original design were omitted to expedite the process and save costs, including additional amenities on the lower level such as a kindergarten, a fact lamented by architect Johannes Uhl during a 2019 panel on the state of the NKZ. (Failed Architecture, 2019).

A multicultural neighborhood

During the urban renewal period beginning in 1963, Kreuzberg experienced a massive influx of Turkish migrants. This demographic shift occurred amidst extensive construction and demolition activities, coupled with significant disinvestment in district amenities and maintenance, leading those who could afford it to relocate (Dell, 2021). Left behind were primarily the poor, elderly, and recent migrants from the Turkish Guest Worker program. Originally initiated to address the postwar labor shortage, exacerbated by nearly 10,000 commuting laborers trapped behind the Iron Curtain, the program was established in 1961 through a bilateral agreement between the German and Turkish governments (Prevezanos, 2011). While initially envisioned as a two-year commitment for unmarried Turkish men to work in Germany before returning to Turkey, practicalities led to indefinite extensions of their stay and the eventual inclusion of their families. Employer-sponsored housing struggled to accommodate the influx, resulting in nearly one million Turks remaining in Germany by the end of the recruitment period in 1973, with a significant portion settling in Kreuzberg.

During the urban renewal period beginning in 1963, Kreuzberg experienced a massive influx of Turkish migrants. This demographic shift occurred amidst extensive construction and demolition activities, coupled with significant disinvestment in district amenities and maintenance, leading those who could afford it to relocate (Dell, 2021). Left behind were primarily the poor, elderly, and recent migrants from the Turkish Guest Worker program. Originally initiated to address the postwar labor shortage, exacerbated by nearly 10,000 commuting laborers trapped behind the Iron Curtain, the program was established in 1961 through a bilateral agreement between the German and Turkish governments (Prevezanos, 2011). While initially envisioned as a two-year commitment for unmarried Turkish men to work in Germany before returning to Turkey, practicalities led to indefinite extensions of their stay and the eventual inclusion of their families. Employer-sponsored housing struggled to accommodate the influx, resulting in nearly one million Turks remaining in Germany by the end of the recruitment period in 1973, with a significant portion settling in Kreuzberg.

The hastily constructed NKZ emerged as a significant housing center for these former guest workers, quickly becoming the focal point of this increasingly Turkish neighborhood. However, cracks began to appear in Schmidt’s hastily constructed project. Structural issues, such as literal cracks in the bridge above Adalbertstraße and deficiencies in elevator maintenance, trash disposal, and overall upkeep, manifested less than a decade after its opening. These deficiencies led to many units remaining unoccupied. By 1998, the NKZ was on the brink of bankruptcy until new managing director Peter Ackermann took charge. Ackermann addressed issues stemming from the complex’s layout, which had contributed to disproportionate levels of drug-related crime (Exberliner, 2016). His initiatives included improved lighting in unsafe areas and securing stairwells accessible only to residents. Additionally, Ackermann revitalized previously vacant shops on the lower level of the NKZ, discouraging crime and generating additional income for the development. These efforts stabilized the financial situation of the NKZ, albeit precariously, with projections suggesting that the original debts will be paid off by 2067 (Failed Architecture, 2019).

Walking around the NKZ today, aware of its problematic and convoluted history, I can’t help but be struck by the meticulous upkeep and seamless integration of commercial and residential spaces. Crossing Adalbertstraße, I find myself in a tucked-away plaza adorned with a Turkish bookstore, a playground, and the Institut für Transnationale und Transkulturelle Soziale Arbeit—a school with barred ground floor windows, the bars arranged in a modernist polka dot pattern for both safety and aesthetic appeal. This architectural fusion of utility and design serves as a reminder of the stark contrast with the vertical, rusted prison-style bars often seen in American public housing developments.

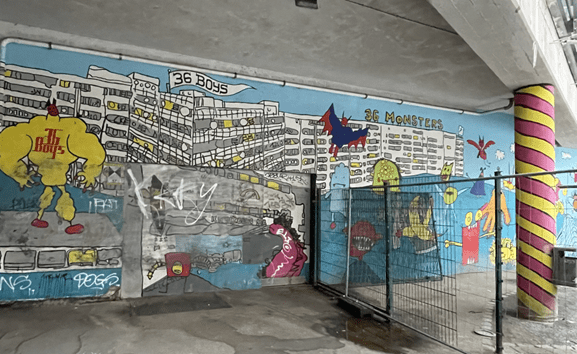

As I traverse the plaza, my attention is drawn to a mural facing the playground. It depicts a whimsical rendition of the NKZ, complete with satellite dishes adorning every balcony—a trademark of Turkish migrant residences in the area. Atop the building’s roof flies a flag bearing the name “36 BOYS,” a reference to a predominantly Turkish gang that once operated in Kotti until the late 90s. Yet, the mural’s rightmost side boldly proclaims “36 MONSTERS,” portraying a host of childlike beasts with brightly colored scales, wings, and beady eyes approaching the building. The faded paint and endearing art style lead me to interpret this not as gang graffiti, but rather as a delicate reflection on Kotti’s complex past and present.

Walking back across the central plaza of Kottbusser Tor, past the Istanbul Supermarkt and down Reichenberger Straße for a block, I encounter more dense apartment buildings. Though their balconies, some adorned with Turkish flags, don’t extend over the sidewalk. However, turning right onto Erkelenzdamm Straße, the housing landscape shifts rapidly. Buildings of similar height to those on Reichenberger Straße, which offer five stories of apartments, now feature four or even three luxurious floors complete with tall, rounded windows and gated-off Hinterhöfe. A man loudly converses in German into an earpiece several stories above me on a wide balcony. One courtyard gate, however, is left ajar. Silently, I step inside and receive a hostile look from one of the residents, even by German standards. The courtyard boasts a full CCTV system monitoring the parked Mercedes truck and a beautiful yet utilitarian metal spiral staircase leading to the rear roof of the building. Most striking are the bicycles tucked to the side of the door. Unlike every other bicycle I’ve seen in Kotti, whether on the street or around the back of a property, all 11 of these are left unlocked and unattended.

Returning to Kottbusser Tor, I venture another block southeast. I pass the Queen Palace Turkish wedding venue, whose use of the Google review star icon in excess of five always amuses me. From the gates of the Queen Palace, I catch a glimpse of the top of the Mevlana Moschee Berlin, mostly obscured from street view. Deciding against entering, I continue onto Mariannenstraße, standing between two apartment complexes on either side of the street. On my left, I encounter the most dilapidated building I’ve yet seen in Kotti. Graffiti drips down each unit’s front door, and long cracks stretch up the concrete walls. Across the street stands a quaint corner building freshly painted in various shades of pale yellow and turquoise. Striking orange covers the long balconies, included in all street-facing apartments. I observe a sprawling courtyard, the snow shoveled off the walkways but undisturbed atop the wide grass fields. The gate to the courtyard is locked. Consulting my phone, I discover the former building is a privately-owned complex with a unit currently on the market for €1,260, while the latter is public housing.

Encroaching gentrification

The NKZ and its surrounding area are far from utopian. It’s a neighborhood disproportionately marked by danger, even as rents steadily rise due to encroaching gentrification. Some might critique the density and living conditions within the massive building, or argue that such a structure shouldn’t occupy Kottbusser Tor in the first place. They may view my fascination with the project, both architecturally and functionally, as overly romanticized or tainted by the American expectation of public housing being in a state of disrepair. And there’s some validity to that viewpoint; American public housing has historically been synonymous with poor or unlivable conditions. “Soon conditions like those in Harlem?” read a headline in a conservative German newspaper back in 1973.

However, today, despite Kotti’s designation as an area burdened by crime, notwithstanding the aesthetic and architectural criticisms many Berliners have regarding the building’s prominent yellow frame, and despite the absence of certain amenities from the original 1970s blueprint, the NKZ remains remarkably functional—it is the vibrant pulse of Kotti. Architect Johannes Uhl shares a similar perspective. Now in his early 80s, Uhl is not a well-known figure recognized in public and often commutes from his home in Lichterfelde to enjoy tea at Café Kotti, located on the elevated walkway of the NKZ. In a 2014 interview with the Berliner Zeitung and during a 2019 panel discussion about the NKZ, Uhl openly expressed regret over the corrupt and challenging process surrounding the building’s construction and subsequent decline. However, he ultimately takes pride in seeing his vision gradually come to fruition over the past two decades. He considers his plans for a housing development seamlessly integrated with the surrounding commercial core a success, and as one wanders through the bustling Kottbusser Tor today, it’s hard to disagree with him.

* Jack Bobley is Goldfish Funeral: a musician, multimedia artist and engineer from Washington, DC. His works reflect upon the intimacies of grief as well as the feeding and interpersonal behaviors of marine life. He currently studies recorded music at NYU Tisch. Jack was in Berlin during the Fall 2023 semester.

* Jack Bobley is Goldfish Funeral: a musician, multimedia artist and engineer from Washington, DC. His works reflect upon the intimacies of grief as well as the feeding and interpersonal behaviors of marine life. He currently studies recorded music at NYU Tisch. Jack was in Berlin during the Fall 2023 semester.