Whiteness Closing Ranks – Avgi Saketopoulou

In 2018, a few days before the start of an international psychoanalytic event, conference organizers sent a group email to those of us who were going to be moderating panel discussions. The email alerted us to the possibility that some conference participants, upset by the organization’s decision to hold a forthcoming conference in Tel-Aviv, might become “disruptive” during the Q&A. The co-chairs wanted “each of you [the panel chairs] to understand that you can call for security assistance if you find that you are unable to work with the person in question”. The co-chairs urged moderators to have their cell phones handy: “someone will immediately be sent to help you.”

I wrote to the co-chairs, asking that the instruction be reconsidered; calling security, I said, on account of feeling threatened and/or imagining that violence is imminent, may sound logical and benign, but it is always already racialized. Because the threshold of “being unable to work with” someone would be significantly lower for black and brown versus white persons, this instruction would surely disproportionately impact people of color. Further, involving “security” seemed like an unnecessary escalation tactic that could put people of color at risk.

Rather than acknowledging the problem, the organizers doubled down; “[w]e do not want any of our members or attendees to feel unsafe or unsupported as they participate in the conference program. The [conference] hotel has security available for just this reason”. The implication was that safe participation could not be reconciled with sensitivity to racially charged matters. The “safety” in question was, and has long been, the safety of white people. Enforcing this selective “safety” puts people of color, and especially black people, at risk.

There is no question in my mind that the original instruction (to call security) and the organization’s response (doubling down) were not intended to harm. Rather, they seemed to me to be oblivious; oblivious to the history of the brutal over-policing of black and brown bodies, and to the dangers —to some bodies — of calling “security”. In that sense, the instruction was racist in the structural sense of the word, and in the quotidian way in which all of us who are white can be cluelessly racist. But the fact that it wasn’t hate-driven or malicious, does not make it benign. And ironically, the conference topic that year was othering and immigration! To this day, as far as I know, IARPP has not acknowledged the structural racism and the imperial whiteness from which this problematic instruction issued. Nor has it taken responsibility for its defensive response or issued apologies to the people of color who protested the unnecessary invocation of “security”.

Said differently, IARPP acted not with intent to harm but, rather, from the standpoint of a whiteness that is unaware of its impact. That this whiteness harms, and does so naïve to its effects, is what we mean when we talk about white privilege. For those of us who are white, slipping into such errors is inevitable. But when a racialized enactment is brought to our attention, and we then, knowingly and defensively, refuse to engage with the problem or to amend our behavior, we enter different territory: that of knowingly defending whiteness. Whiteness shores itself up by doubling down, and by closing ranks at precisely the switch point where it becomes aware of its own racism.

And while as analysts, one would think that we might be well positioned to not become defensive, we have often seen this doubling down on our listserv. Here’s how it usually goes: Dr. A posts something racially offensive which, 99% of the time, is not hateful or intentionally hurtful. Dr. B and Dr. C say they are hurt, and note the problems of the post. Then, whiteness closes ranks: Dr. X and Dr. Y jump in to defend Dr. A. Quickly, the moral compass goes haywire: Dr. A is now portrayed as having been assaulted by, and to be in need of defending from, the non-analytically minded (read, impassioned-rather-than-contained) Drs B and C. Others tepidly acknowledge something was off in the original post, but they equivocate. They denounce the racism but, at the same time, urge understanding and the recognition of “both sides”. This, by the way, is how privilege works: I step on you. You screech “ouch” in pain. Annoyed, I turn around and chastise you: “your screeching hurt my ears!” Stop screaming, be polite, the by-stander advises.

This “both-siderism”, as Pellegrini (forthcoming) calls it poses as even handedness. But it’s pernicious in that it reframes the conversation from “Dr. A did something problematic which has hurt Dr. B, who spoke up” to “Dr. A did something, Dr. B. did something back, and everyone needs to own their aggression”. “Both-siderism” is one of the ingredients of what the black feminist theorist Cathy Cohen calls “performative solidarity”: activism that showcases one’s virtuous involvement rather than substantially helping the cause one purports to advocate for.

If you are wondering what you can do to help with the racism on our listserve, stop participating in the closing of whiteness’s ranks. Next time a Dr. A posts something racially offensive, refrain from rushing in to defend them from having to consider the impact of their words. Let them feel their feelings when someone yells “ouch!” to them. This is not about abandoning our beloved colleagues to a politically correct mob; it is to allow them to be held accountable. If you are wondering why it’s so hard to retain candidates of color, I am confident that white solidarity is one important reason.

With time, we may even be able to shift from a focus on the injury of being “called out” to seeing that being “called out” is a courageous gift: the gift of having something brought to one’s awareness. We are not doing ourselves or each other any favors by soothing our friends and colleagues against the anxiety, pain, and discomfort that comes with noticing – and reckoning with – our racism. What is at stake is humility, not humiliation.

When the IARPP debacle was playing out, a white colleague went around saying that I had “shot myself in the foot”. He told me he had meant this protectively; he was concerned that I was alienating myself from important people in the organization, that it wouldn’t be good for my career. He was not wrong in that respect, but he was wrong in another, more important way. The expression “shooting oneself in the foot” refers to unintentionally harming oneself. But in this context, it also marks how whiteness closes ranks: white people advising each other to safeguard our privilege by not stepping into the fray.

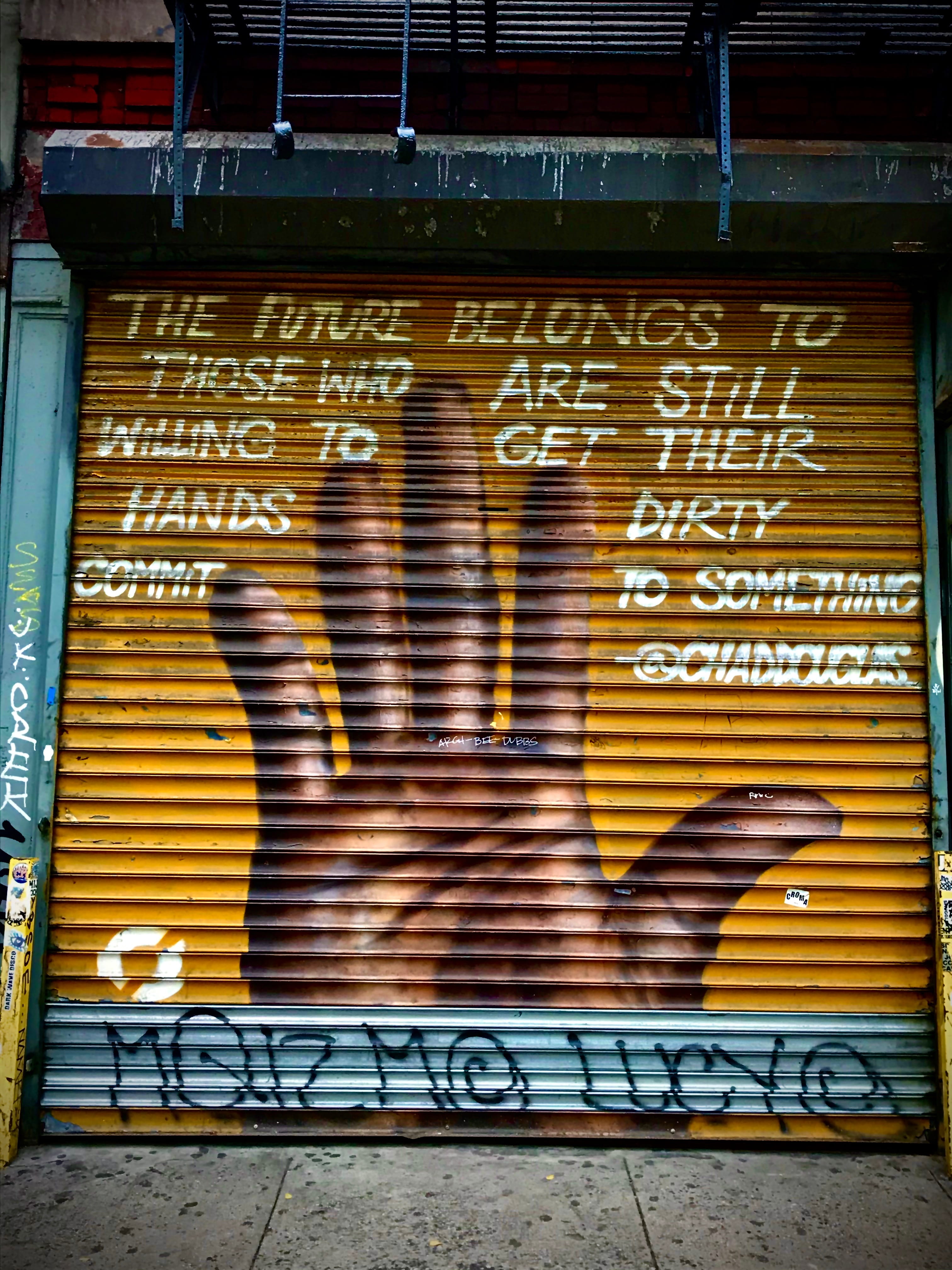

If we want to be mindful of our white privilege, we have to be willing to put some things of our own -privilege, access, even the smoothness of some professional relationships- on the line. Anti-racist work is not work that can be done with a ten-foot pole and from a distance; you have to roll up your sleeves and step into the fray. And if you do, rest assured you’ll get a bit banged up along the way; we get banged up when we name others’ racism, and we have to permit ourselves the discomfort of getting banged up when someone else names ours.

Those of us who are white need to put ourselves between our institutions, even our beloved organizations, and our colleagues of color. We need to do so not out of self-destructive naiveté that amounts to shooting oneself in the foot, but because the proverbial foot that we want to protect may, in fact, be the foot of white privilege, which for too long has held black bodies to the ground.

References

Cohen, C. (2014) #DoBlackLivesMatter? From Michael Brown to CeCe McDonald On Black Death and LGBTQ Politics. Kessler Award Lecture, CLAGS, December 12. Retrieved March 12, 2015 from: http://www.racismreview.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Cohen_CLAGS_Transcript_121214.pdf

Pellegrini, A. (forthcoming). In, Zeavin, L. & Moss, D. (Eds.) Hating, Abhorring and Wishing to Destroy: Psychoanalytic Essays on the Contemporary Moment. London: Routledge, New Library of Psychoanalysis.

Avgi Saketopoulou trained at NYU PostDoc, where she now teaches an intersectionally-informed course on psychosexuality and polymorphous perversity. She is also on the faculties of the William Allanson White Institute, the New York Psychoanalytic Institute, the Stephen Mitchell Relational Center and the National Institute for the Psychotherapies. On the editorial boards of Psychoanalytic Dialogues, The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, and Studies in Gender and Sexuality. She is currently working on a solicited book manuscript provisionally titled: “Overwhelm: Risking Sexuality Beyond Consent.”