(Re)Appropriating Art: Dynamism and Discourse via a Political Mural

by Vlad Maksimov

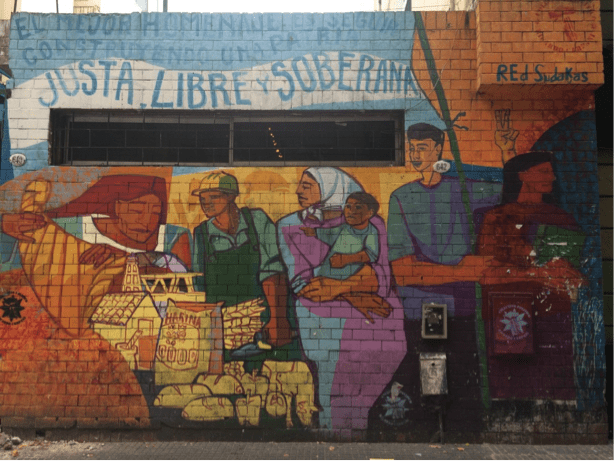

The mural analyzed in this essay is located on Avenida de Mayo, a few blocks from Plaza de Mayo, on one side of a parking lot gate. The mural was initially created by Red Sudakas, a kirchnerist Argentine artistic collective expressing its views through murals and political participation. However, characterizing their political stance as limited to solely supporting the current government is unjust. The introduction to their proclaims that “We are from this continent that is awakening…We are the mixture and the rhythm.” Their murals carry messages of Pan-Hispanoamericanism, the appreciation of hard work and envision the state as the primary promoter of such values. Their name itself is professing the reappropriation of the traditionally pejorative term used to describe South Americans, homage to their larger vision and ideology.

This mural is wholly conversant with these ideas. It depicts five archetypal figures representing the ideal citizens of Argentina and the country itself. The obrero, the blue-collar worker, wearing his construction cap with a construction tool in his hand is embodying the cornerstone of peronist Argentina. Behind him the mother holding her child is representing the primordial importance of family. Moreover, she is wearing a white headscarf, a clear reference to the symbol of Madres and later Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo, the former being the first organization that called international attention to the outrageous human rights violations during the last military regime. Her recuperated  child, one of the desaparecidos, is pointing toward the personification of Argentina, a woman dressed in the colors of the national flag; she is pouring the riches of the “patria” out of a cornucopia, the horn of plenty. Flour, wheat, a farm, a factory, a loaf of bread, cattle, mate and fruits all represent the abundance and the nourishment the homeland is providing for its people. On the far right, the couple is representing the young future generation; the smiling male figure is simultaneously holding his sweetheart and the national flag in one hand and showing the peace sign with the other. Intriguingly, the female figure is looking away from all the other participants in the scene, as if rejecting the values represented by the mural. She is tightly clutching two books, a classic symbol of education and knowledge. This could perhaps be a commentary on the dangers posed by an arrogant, authoritative, unpatriotic and ‘indoctrinating’ educational system that does not respect the ideals portrayed by this piece of art. The text on the flag reads: “The best homage is to continue building a just, free and sovereign homeland,” suggesting a complete rejection of any kind of foreign dependence, proclamation of democracy and support for a domestic-market oriented economy.

child, one of the desaparecidos, is pointing toward the personification of Argentina, a woman dressed in the colors of the national flag; she is pouring the riches of the “patria” out of a cornucopia, the horn of plenty. Flour, wheat, a farm, a factory, a loaf of bread, cattle, mate and fruits all represent the abundance and the nourishment the homeland is providing for its people. On the far right, the couple is representing the young future generation; the smiling male figure is simultaneously holding his sweetheart and the national flag in one hand and showing the peace sign with the other. Intriguingly, the female figure is looking away from all the other participants in the scene, as if rejecting the values represented by the mural. She is tightly clutching two books, a classic symbol of education and knowledge. This could perhaps be a commentary on the dangers posed by an arrogant, authoritative, unpatriotic and ‘indoctrinating’ educational system that does not respect the ideals portrayed by this piece of art. The text on the flag reads: “The best homage is to continue building a just, free and sovereign homeland,” suggesting a complete rejection of any kind of foreign dependence, proclamation of democracy and support for a domestic-market oriented economy.

The artistic style of this mural is clearly in conversation with the traditions of Mexican muralism, which is characterized by setting a politically salient agenda for art. This school understands the main objective of artistic expression to be proactive; a zealous medium for social communication and ideological dissemination. The great artists that have worked in this vivid, figurative style include the “los tres grandes” in Mexico: Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros. In Argentina, the first considerably similar movement in sentiment and ideology are the works of the “Movimiento Espartaco.” Painter Ricardo Carpani, considered to be one of the most renowned members by several commentators, was part of this artistic movement.

In fact, Colectivo Político Ricardo Carpani (CPRC), that similarly to Red Sudakas is an artistic collective primarily producing socio-political murals, seems to have added certain details to the art piece. In the lower left corner, as well as on the right edge of the piece, we can see stenciled human face, presumably of the desaparecidos. This technique creates a haunting effect of a phantasmal, yet inescapable presence of a tragic past that in reality forms the very fabric of the nation; these ghostly beings are the building blocks of democracy and reminders of the true importance behind the ideals promulgated by the mural. This artistic choice, however, is not incidental. It is an artistic reference Antonio Berni’s La Gran Illusión or La Gran tentación (1962), another prominent member of the Argentine muralist movement. In that work the artist depicted his fictitious character, Ramona Montiel, a woman who discovered that prostitution was more lucrative than working as a seamstress. Her body is covered with faces of men who passed through and shaped her life in various ways.

This collaboration between the artistic collectives Red Sudakas and CPRC is not surprising. The two groups have worked together in the past, in fact, on the very same wall, in a project titled YPF: sovereignty is to recuparate what is ours (2012). However, perhaps the most fascinating twist in this brick wall’s fate came very recently. Two portraits replaced the two rightmost figures and the Red Sudakas’s signature was removed, while the CRPC’s logo remained untouched. Though there has been a clear attempt to follow the original artistic choices and style of Red Sudakas, the two figures are clearly painted by different artists. This difference manifests in more elaborate shading, as well as cleaner and crisper lines that are reminiscent of stenciled portraits. The male figure on the left is Francisco ‘Paco’ Urondo, an Argentine poet, journalist and an active member of the Montenero movement who died in an armed confrontation with supporters of the Junta in 1976. His killers were given harsh sentences for his murder and other crimes committed during the military regime in 2011. Painted on the right is Urondo’s friend, Roberto Walsh, a writer, journalist and political activist, an ardent critic of the Junta and a member of the Montonero movement. The deaths of his friends, including Urondo, and his daughter, María Victoria, pushed him to write the notorious Carta Abierta de un escritor a la Junta Militar, which he mailed to several editorial departments of newspapers but at the time none of them published it. On the following day, March 25th of 1977, he was kidnapped by ESMA and never seen again.

The occasion for the modification of the mural was probably the Day of Remembrance of Truth and Justice on May 24th, commemorating the military coup and the atrocities that followed. This day also coincides with the day Walsh sent his open letter. Though the authorship of the modification is  unclear, there are at least two distinct possibilities. First, it is possible that, just as with the faces of the desaparecidos, CPRC has added another element to the mural. This could explain the difference in style. The second possibility, and what seems more plausible, is that La Campora, a kirchnerist political youth movement, which also has a mural on the ther side of the parking lot’s gate has modified the movement to reflect the current political tensions in the country. This hypothesis is also evidenced by the enhancement of the underscored “P” to the right of the obrero’s helmet, which the traditional signage of the group. Unfortunately, neither of the interpretations explain the reason for the removal of Red Sudaka’s signage but tolerance of the CPRC logo. Furthermore, the La Campora has cooperated with Red Sudakas previously on a different mural in October 2014, so there should be little animosity between the two groups.

unclear, there are at least two distinct possibilities. First, it is possible that, just as with the faces of the desaparecidos, CPRC has added another element to the mural. This could explain the difference in style. The second possibility, and what seems more plausible, is that La Campora, a kirchnerist political youth movement, which also has a mural on the ther side of the parking lot’s gate has modified the movement to reflect the current political tensions in the country. This hypothesis is also evidenced by the enhancement of the underscored “P” to the right of the obrero’s helmet, which the traditional signage of the group. Unfortunately, neither of the interpretations explain the reason for the removal of Red Sudaka’s signage but tolerance of the CPRC logo. Furthermore, the La Campora has cooperated with Red Sudakas previously on a different mural in October 2014, so there should be little animosity between the two groups.

In order to discover whether this art piece is legal, an employee of the parking lot was approached with questions regarding the history of the mural. Remarkably, the employee did not even realize that the murals at the entrance to the parking lot were recently modified. To the question whether these murals were permitted he gave an affirmative answer. To get a sense of the public opinion, three pedestrians we asked what they thought about the pieces. Two of them answered that they thought it was pleasant have something colorful on the wall, while the third person said they would prefer not to have explicitly political messages displayed so close to Plaza de Mayo. When asked if they have ever stopped to look more closely at the mural all three answered no.

The life of this wall serves as a telling example of the dynamism of public art, especially in a political context. As opposed to galleries, ideologies, stances and messages here are constantly contested, displaying a struggle of ideas and beliefs. The physical space is the skin of the city that is being written on but not tattooed. The messages are ephemeral and transitory, embodying the heart beats of political movements. Properties of others are used to question propriety, the non-artistic participant is given the chance to participate in the interrogatory and, at times, indoctrinating dissemination of ideals through giving right to use their walls as canvasses. However, once this concession is made, the canvass turns into a messaging board. Through this, as Alison young points out, the “public and private space are now closely intertwined. …Public availability becomes contingent on permission granted by the private interests controlling a space.” However, as mural discussed here shows, once that permission is granted total control of the space becomes impossible.♦