THE CENTRO

The Centro Beat lies on the boundary of two administrative units of Buenos Aires, Barrio. San Nicolás and Barrio Montserrat. Though administratively the neighborhoods are divided now, the area as a whole is the beating historical and political heart of the city and, arguably, the entire

country. Argentina’s history as an independent nation is undeniably tied to what today is known as Plaza de Mayo, Casa Rosada, which houses the executive branch of the government, and Congreso, the Argentine congress.

The city was founded twice, first in the area that is today called Barrio San Telmo.[1] However in 1580, nearly fifty years after the initial abandonment of the settlement due to attacks from the native population, Buenos Aires was founded once again, this time slightly north from the first settlement, in today’s Montserrat with the first port being constructed on the shore of Río de la Plata.[2]

Plaza de Mayo and other frequented locations in the area such as the Obelisco continue to be people’s favored spot for protest; on any given day there may be a different political group or minority organizing in the lower side of Centro along Avenida Nueve de Julio. The rich history of politics and protest, coupled with many famous landmarks including the Teatro Colón, has also made Centro a primary commercial tourist attraction; an interesting contrast of many upscale cafés, hotels, and restaurants can now be found as well as cultural attractions such as museums, movie theatres, music and food festivals.

Plaza de Mayo and other frequented locations in the area such as the Obelisco continue to be people’s favored spot for protest; on any given day there may be a different political group or minority organizing in the lower side of Centro along Avenida Nueve de Julio. The rich history of politics and protest, coupled with many famous landmarks including the Teatro Colón, has also made Centro a primary commercial tourist attraction; an interesting contrast of many upscale cafés, hotels, and restaurants can now be found as well as cultural attractions such as museums, movie theatres, music and food festivals.

Being politically and commercially important also makes this part of the city a priority regarding infrastructure; Centro/Plaza de Mayo can be easily accessed by any of the city’s otherwise sparsely located Subte (metro) lines. Subway lines in Buenos Aires all converge in the Centro Beat, in two ‘knots,’ located at the Obelisco and Plaza de Mayo. The subway system is “a powerful shaper of both public space and collective behaviour, … [it is] both an agent of social change and a socially constructed space in itself.”[3] Hence, the fact that nearly all lines converge here, and only here creates an intriguing dynamic, where Centro’s historical and political importance is reflected in the infrastructural layout of the city as well. Subways tend to democratizing spaces that have the power to shape public space through the circulation of various groups of people. During rush-hour the poorly air-conditioned trains fill to the brim with people that represent all socio-economic strata of the society, contributing to the temporary coexistence of normally segregated groups of people. These confined spaces function as the blood-supply of Buenos Aires, all leading to its heart; Centro.

Barrio San Nicolás was named after the church of San Nicolás that stood at what today is the intersection of Carlos Pellegrini and Corrientes, which is also the location where the flag of Argentina was raised for the first time.[4] Today this site is commemorated by the Obelisco of Buenos Aires, which was inaugurated in 1936 to celebrate the fourth centenary of the city’s first foundation and presently is a favored spot for political protests and demonstrations.[5]

The Montserrat neighborhood, on the other hand, is named after the Virgin of Montserrat, a black Madonna and the patron saint of Cataluña, who was affectionately referred to as “La Morenita” or “the dark-skinned one.”[6] Due to her dark skin she was well liked by the black population of Buenos Aires. Though today there are not many blacks left in Buenos Aires, by the end of the 18th century up to 40% of the city’s population was black or mulatto,[7] and the neighborhood’s name is one of the few surviving reminders of their presence.

Avenida de Mayo is the northern frontier of Montserrat and connects perhaps the two most important squares in the country, Plaza de Congreso and Plaza de Mayo, creating a physical link between the executive and legislative branches of the government. The first high-rise buildings of the city were built here in the second half of the 20th century, and the avenue is known for its Art Nouveau and Art Deco architecture.[8] Its eastern end opens on Plaza de Mayo, indisputably the most important historic site of Argentina.

In terms of its demographics, this is one of the highest populated areas in Buenos Aires. The total population, shared between barrios Constitución, Monserrat, Puerto Madero, Retiro, San Nicolas and Santelmo is 249,433. The average income in these barrios would be considered-mid range compared to the entire city, ranging between 4583.45 to 4390.35 Argentine pesos a month, compared to 7002.96 pesos in the highest income areas in the north of the city and 3230.69 in the south.[9] These income levels reflect some historical trends. During the 19th century yellow-fever epidemic aristocratic families, in order to escape the infection, fled to the north of the city to the area that would become today’s barrio Recoleta, whereas the financially disadvantaged population remained in the South.

This latitudinal, north-south, divide remains to this day, we the northernmost barrios being the richest, while most villas or shanty towns, can be found in south of the city. Monserrat and San Nicolas remained in the middle, on the border of this divide. The income levels also correspond with the political alliances. In the 2011, Cristina Kirchner obtained the majority of the votes in this area (37.39% in Sección 1, Comuna 1 and 39.46% Sección 3, Comuna 3), but percentages are significantly lower than in many areas of Gran Buenos Aires, where Kirchner was able to win more than half the votes, thus corresponding to the area’s position in ‘the middle.’[10]

As mentioned previously, Plaza de Mayo is perhaps historically the most important public space in Argentina. The square used to be divided into two plazas throughout the beginning of the 20th century, Plaza Mayor and Plaza de Armas, separated by la Recova, a colonnade that served as the first commercial gallery of Buenos Aires.[11] In 1883 la Recova was demolished and the square took its current form. [12] It is named after the revolution of May 25th of 1810, an homage to the mass demonstrations that occurred here and eventually led to the independence of the country.[13] Though traditionally symbol of government power and the rule of higher classes, this public space was claimed by the middle and working classes once and for all on October 17th, 1945, simultaneously marking the end of the “Infamous Decade” of economic devastation and the consequent two-year military rule, and the birth of peronism.[14] The rise to power of Juan Domingo

Perón is perhaps the single most important moment in Argentine history, as it leaves the society divided politically to this day. Under his rule, exile and return, Plaza de Mayo becomes the ultimate public space for the working class and other supporters to connect to their leader. From this moment on, as depicted by the historic photograph Las patas en la fuente (“Paws in the fountain”) showing workers washing their feet in a fountain in the square, Plaza de Mayo is no longer a privileged location for the high classes, it is a transcendent space to personally connect, support, oppose and rebel against the government. As suggested by Daniel James, the mass demonstrations of October 1945 make it “difficult to imagine a more encapsulated expression of the clash of behavioral and notions of propriety.” [15] From this point onward, the working class and activists of other social and political affiliations will unapologetically invade public spaces to express their stance regardless of what would be considered “proper,” eradicating the social boundaries of segregation between aristocracy and the rest of society. Perón makes a complicated network of alliances with actors from various points of the political spectrum during his exhile after a result of a military coup.

This leads to an increasing fracturing of peronism as a political ideology. It finally becomes evident that some groups within the peronist movement can no longer be reunited after Perón’s return in 1973, when he expels the right-wing peronist Montoneros from Plaza de Mayo. [16] As a result, to this day a multitude movements from all points of the political wheel label themselves as “peronist,” making the meaning of this term almost intangible. This has several implications for the political art in this area. For instance, actors that identify as peronists themselves continually contest the messages of political murals created by other peronist groups that have at times take a radically different political stance. All these events, however, took place in the same place where the movement began, in Plaza de Mayo.

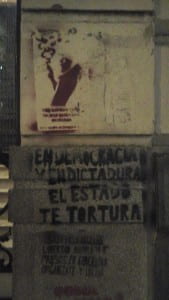

After the subsequent death of Juan Perón in 1974, his third wife, Isabel Perón came to power. Her weak rule, however, was ended by a military coup in 1976, which established a dictatorship that would last until 1983. The new government, titled the National Reorganization Process, was ruled by a military junta of three members, one with the title “President” and two other members in charge of the navy and air force. This dictatorship is considered one of the most oppressive and terrorizing regimes in 20th century Latin America; it is most known for the “Dirty War”, an ongoing internal process of monitoring and murdering citizens who appeared to threaten the military rule.[17] The government targeted and imprisoned members of left wing movements, revolutionaries, and anyone associated with socialism. This also marked the beginning of a practice of forced disappearances in which these perceived opponents of the dictatorship were abducted secretly and without warning by the military in unmarked vehicles. These “disappeared” people were often imprisoned in detention camps, tortured, and killed.[18]

Some relatives of disappeared found evidence that the newborn children of prisoners were being given away to military families, and shortly thereafter the group Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo (Madres de Plaza de Mayo) was formed. The Madres started demonstrating weekly on April 30th, 1977 in the Plaza which faces the presidential Casa Rosada; they made signs and wore white headscarves with the names of those lost, and demanded the return of their missing children and grandchildren. Their protests became the first public demonstrations against the dictatorship, turning into a symbol of the nation’s resistance to injustice and terror.[19] Their symbolic white scarves are now painted on the ground at the May Pyramid, the monument at the center of the Plaza around which the mothers would circle in their marches. At the group’s inception the reason for this circling was that the junta would consider a large public gathering to be protest and immediately identify and ban it– but since the Plaza de Mayo remained a public space free for the people to walk through, they could protest as long as they were moving. United in their common identity of motherhood in the social context of machismo, the invasion of the public space by enraged women whose “role as protectors within the home” were violated by “the kidnappings that invaded the home domain.”[20]

Appraised as a gathering of women in public, outraged by the invasion of the private space that was designated as proper by the oppressive machismo, ‘their’ space used as a crime scene to exterminate their own children completely re-signified the meaning of the protests in terms of gender and in terms of symbolic confrontation of the regime. Marching around the Pirámide de Mayo, commemorating and embodying the freedom and sovereignty of Argentina, gave this movement an almost performative quality, as well as stronger symbolic force. The Madres managed to re-appropriate and re-signify the space of Plaza de Mayo as public in a context of a regime that denied it to be so.[21] Still, this was not entirely without consequence; by the end of 1977, fourteen of the original members have disappeared.[22] The government called them Las Locas (crazy women), attempting to trivialize their protests. Nevertheless, their gathering in a symbolic space of freedom, confronting the state incarnated by Casa Rosada, the effective utilization of “gender-associated weakness and diapers and kerchiefs repreenting the helplessness of children,” re-defined the image of the disappered, unraveling “the guise of legitimacy around the kidnappings.”[23] Although they did not have many members at first because citizens were fearful of speaking out in front of the dictatorship, the group slowly gained and sought out international media attention[24] with the rise of the number of the disappeared.[25]

Though today the Madres can still be found marching weekly they have sectioned off into a group dedicated to the original cause of finding the lost grandchildren, and another focused on current, slightly more radical political motives. The country’s relatively fast failure in the Falklands War was enough to destabilize the military and the nation’s confidence in the junta; the Madres held a “24-hr March of Resistance” on the Plaza in December of 1982 and were joined by thousands. Shortly thereafter the dictatorship was dissolved in 1983 with a democratic election.[26] Today, the headquarters of Universidad Popular Madres de Plaza de Mayo, a faction is of the original movement, is located on Hipólito Yrigoyen 1584, close to the Argentine Congress. Their legacy, however, extends far beyond their present activities. They continue to inspire feminist organization that flock to the Pirámide de Mayo to express their discontent with government. For instance, the fences of surrounding the inner part of Plaza de Mayo are covered with writings of Las Rojas, a socialist-feminist organization discussed below.

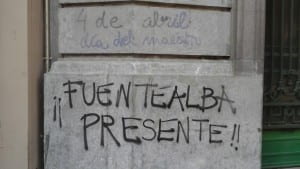

Thus, the cultural heritage of the area is closely linked to its historical significance and political past. The hyperpoliticized nature of Centro is underscored by the political graffiti that covers Avenida and Plaza de Mayo, highlighting how deeply embedded political involvement is in Argentine history and culture. Some words used have origins from the 1976 military dictatorship; “nunca más” is a phrase seen ubiquitously in various forms that refers to the title of the report detailing the full extent of the dictatorship’s actions during the Dirty War.[27] Simply meaning “never again”, the phrase has had continued symbolism and power, especially as the public has become increasingly disillusioned during recent controversy surrounding the death of prosecutor Alberto. In January 2015, Nisman was found dead “ hours before he was due to appear before a congressional committee to present more details of his allegations” against the current President of Argentina, Cristina Kirchner.[28] On February 18, a rally attended by hundreds of thousands commemorated his death, which necessarily needs to be understood in the context of the politically and historically charged sensitivity around state-sanctioned killings, alleged or otherwise.[29]

More conventional and established forms of public art have also utilized this space for its historical, cultural as well as political importance. A notable example is Marta Minujín’s piece title The Parthenon of Books/Homage to Democracy, an installation created in celebration of the newly returned democracy in 1983 on Avenida Nueve de Julio, consisting of iron framework completely filled with 25,000 plastic-wrapped books that were previously banned by the terrorist state, consequently becoming dismantled by people taking these books home. This impactful commentary on the power of knowledge and its inalienable value to democracy is an example of artists utilizing the historical and cultural importance of the area to add supplementary meaning to their works.[30]

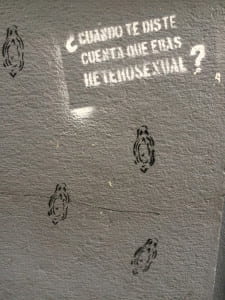

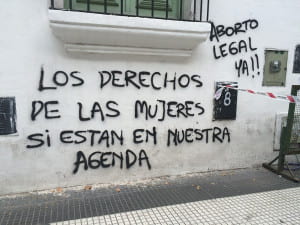

Other frequent political topics appear to be surrounding discourses of Feminist, Queer Rights and Sexual Liberation movements. Abortion is completely illegal in Argentina and this is a major point of protest, as is reflected in the tags “Aborto Legal (Ya)” and “Aborto Legal Seguro Y Gratuito”. Las Rojas, a socialist feminist group focused on these issues and the culturally predominant Argentine “Machismo,” has spray painted such phrases along with their tags and links to social media pages.[31] Another recent tag, “Justicia Por Iara”, is referring to the outcome of an ongoing rape case in which a Buenos Aires policeman has just been pardoned of abusing his stepdaughter despite overwhelming evidence.[32] A protest at the Obelisco was held on March 19th by several feminist and political groups under the “Basta de Femicidios” (Stop Femicide) campaign; one of the members explained that in Buenos Aires a woman is killed every thirty hours, with many being victims of domestic violence. All attendees were impassioned and willing to talk about the cause, carrying signs with photos of specific victims, and some had made more symbolic gestures (eg. placed bags in the shape of a body over subway grates). None of the art in this beat is static. Regardless of the intricacy and medium, tags, graffiti, murals all enter the stream of the ongoing political discourse in the country. Oftentimes sprayed messages will comment on the existing political commentary on the walls, or modify some parts of the piece to morph their meanings. In this way the walls of the buildings become a truly public forum, one that is extremely political, their dynamism and rhythm following that of the country’s life.

All in all, this area is the beating heart of political life in Argentina that must be understood from perspectives of national identity, pride and collective attempts at overcoming seemingly insurmountable tragedies.

The Houston Street beat offers an interesting perspective and look at New York City. Because of its role as a major cross street in Downtown Manhattan, Houston Street intersects multiple neighborhoods, with different economic and social standings, which show the wide variety of people, cultures, and ideas that New York has to offer. Located at the bottom of the numbered street grid that makes up the majority of the island of Manhattan, Houston Street is the boundary between the ordered and disciplined neighborhoods in Midtown and Uptown, and the edgier feel of Downtown Manhattan. The neighborhoods located along Houston Street reflect this tension between the two different atmospheres and are the sources where these ideas met, and the public art reflects this. Therefore, we can use Houston Street as a way to see the differences not just in the artwork, but in how the city itself is composed and the effects that gentrification has had on it. (this is the first reference to gentrification and it comes up rather unexpectedly. Consider prefacing it somewhat, maybe “the effects that the city’s social and spatial evolution has had on it, particularly as it applies to what has been called gentrification”)

Nepotism led to the naming of Houston Street. In the early 1800s when Manhattan was mostly farmland, Nicholas Bayard paved a road through his property. He named it after his new son-in-law William Houstoun, a congressman from Georgia. Eventually the “u” was dropped from the spelling of Houston Street and the Bayard family lived on to intermarry with the Stuyvesants and build much of Manhattan’s modern infrastructure.[1]

The Commissioner’s Plan of 1811 mapped the grid structure of Manhattan and solidified Houston’s utility as a major cross town throughway. This was needed. The 1900s brought about an explosion in population, most of it coming from international immigration. Houston Street marked the northern border of the the Lower East Side. An ethnically diverse working class neighborhood East Houston and the LES housed Irish, Italians, Poles, Ukrainians, and Jewish cultures. West of the LES was a mix of tenements, rowhouses, and converted commercial buildings. This area had a strong Italian-American community as well as a significant Portuguese-American community.[2]

Continuing west along Houston Street, the neighborhoods of NoHo and SoHo emerge. Their names stem from their location – North of Houston and South of Houston, respectively. SoHo has become widely known for its fashion and for the wealth it brings into the neighborhood.[3] When compared against its neighborhoods like Little Italy, Lower East Side, or Chinatown, all areas that have emerged out of the immigrants flocking to New York City and their efforts to preserve many of those cultural ties, these are a stark contrast to the development and recruitment of luxury brands into SoHo as a result of gentrification. It’s been described as the space where the future of art will take place.[4] Yet that is not always welcomed in the area. On a recent walk through the beat, a recent tag “Fuck Soho” refers to some residents of the area’s disdain offer the build up and development in SoHo. Many look to SoHo as one of the first examples of gentrification in New York and refer to the trend as “SoHofication.” A recent Slate article “The Myth of Gentrification” talks about the effects that this process has, and in reality gentrification is not bad.[5] Therefore, SoHo has become the battleground and example to see what will happen with gentrification. However, while the previous and continuing gentrification that takes place in SoHo is important, it is also important to notice the significance of the name. The entire name of the neighborhood is constructed off its relationship to one specific place, Houston Street. This relationship highlights the significance of Houston Street and its growth over the past two hundred years. As SoHo emerged after World War II and the expansion of Houston Street, this seems to be a conscious effort to build up the importance and significance of Houston Street in Manhattan, giving the area much more power and significance to it.

After crossing through SoHo, Houston Street runs through the West Village neighborhood as it runs back to the Hudson River. In comparison to the East Village, the West Village tends to be wealthier (median incomes of between $75,000 and $125,000 compared to around an average of $50,000) and more residential than areas in SoHo or even in the West Village.[6] Walks through the neighborhood seem quieter than in the busier East Village, due partially to the more residential feel of the area and as well as the reduced traffic because of the diversion in Houston Street to the Holland Tunnel. Because of the expansion plan in the 1940s that led to the widening of Houston Street, many of the buildings in the West Village were preserved in an effort to minimize the effects of the development, and therefore retaining much of the character of the neighborhood.[7] Because of these efforts, it has made the neighborhood incredibly popular, and therefore the demand for space has increased as well as the price to be able to purchase or rent property there. This increased demand has allowed for the neighborhood to therefore become one of the desired and more expensive neighborhoods in Manhattan. Therefore with the preservation of many of the buildings in the area, the amount of public art that is located is less than that of other areas of New York.

Originally a narrow cobblestone street, Houston underwent major retrofitting in 1940. To accommodate crosstown traffic, much of Houston Street was widened to six lanes. This process resulted in the demolition of several buildings along the south side of Houston. 20th century New York was a metropolis archetype. Constant development meant gentrification and pushing out of cultures. The widened Houston Street ends at 6th Avenue, but the original plan was for it to continue as a connection to the Holland Tunnel, destroying the South Village. The plans were defeated by community activists.[8]

Houston Street has been a concrete canvas for decades. It’s most famous landmark – The Houston Street Wall – was an active spot for taggers since the early 60s. However it wasn’t until Keith Haring and Juan Dubose that street art on Houston Street was embraced into the city’s culture. The two chose the Houston Street Wall for its central location in the middle of an emerging downtown art scene, and because it was on the direct walking route for artists traveling back and forth between SoHo and the Lower East Side.[9] Soon after Haring’s work the Houston Street Wall itself became a landmark of lower Manhattan. Naturally the wall was acquired in 1984 by Tony Goldman, who used it for advertisements for two decades.

In 2008 the wall was donated to Jeffrey Deitch who commissioned recreations of Haring’s pieces. Deitch continued to feature a variety of street artists from across the world including the Brazilian street duo Os Gemeos who created an original installation on the iconic structure. Following artists included Shepard Fairey, Barry McGee, SACE, and the first solo commissioned female Houston Street Wall Artist Aiko Nakagawa.[10]

The modern landscape of Houston Street is undisrupted commercialism. Italian and Portuguese communities were pushed out years ago. The majority of street art precisely on Houston Street is commissioned, and the street art in bordering LES areas are mostly tags. The reason for the dichotomy is clear: Houston Street has logistical importance to New York City, lots of foot traffic, higher real estate, and a greater public focus on infrastructure and cleanliness. But because the street’s function is neither primarily financial like Midtown or FiDi or residential like the upper West and East Sides, it’s artistic history has been reimagined through public resources. Because of this and its post-gentrified status Houston Street presents an interesting case study for urbanization cycles.[11]

Therefore, we can see that Houston Street seems to serve as a spectrum of New York. Following the progression, we can see how many different cultures and areas there are in New York and how diverse they can be. The diversity and the history between the area especially the transformation from the homes of thousands of poor immigrants through the process of gentrification are reflected not only in the types of street art that is present in the different neighborhoods but also in the abundance in it. A neighborhood like the West Village, focused on preserving and maintaining many aspects of it, is not a welcoming spot for new artists hence resulting in smaller, less visible pieces, which tend to primarily be tags. The prominence of Houston Street as a major roadway linking both sides of Manhattan, makes it the perfect space for street art and helps to give the street are its power to have some sort of significance and meaning behind it. ♦

Centro Footnotes

[1] Seabright, Alan. “Which Buenos Aires Barrio Is for Me?” BuenosTours. BuenosTours, n.d. Web. 25 Mar. 2015. <http://www.buenostours.com/buenos-aires-barrios>.

[2] Bonilla, José. “Buenos Aires, National Capital, Argentina, Cultural Institutions.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica, 22 Jan. 2015. Web. 25 Mar. 2015.

[3] Ronn Pineo and James Baer, “Dangerous Streets, “Trolleys, Labor Conflict, and Reorganization of Public Space in Montevideo, Uruguay”,” in Cities of Hope: People, Protest, and Progress in Urbanizing Latin America(Boulder: Westview Press, 1998), 48.

[4] Rubio, Mónica Ester. “San Nicolás.” Barriada. Ciudad Autónoma De Buenos Aires, n.d. Web. 25 Mar. 2015. <http://www.barriada.com.ar/sannicolas.aspx>.

[5] “Obelisco.” Buenos Aires Ciudad. Gobierno De Buenos Aires, n.d. Web. 25 Mar. 2015. <http://www.turismo.buenosaires.gob.ar/atractivo/obelisco>.

[6] Rubio, Mónica Ester. “Montserrat.” Barriada. Ciudad Autónoma De Buenos Aires, n.d. Web. 25 Mar. 2015. <http://www.barriada.com.ar/montserrat.aspx >.

[7] The fact that the black slave population of Argentina seems to have vanished has drawn much debate, with some historians claiming a covert political, genocide-like “whitening” policy in the 20th century. See Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s discussion of the topic.

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. “True or False: There Are No Black People in Argentina.” The Root. The Root, 12 July 2014. Web. 25 Mar. 2015. <http://www.theroot.com/authors.henry_louis_gates_jr.html>.

[8]The Rough Guide to South America. London: Rough Guide Travel Guides, 2004. Web. 25 Mar. 2015.

[9] Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires, “Banco De Datos: Estadística Y Censos,” Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires, http://www.buenosaires.gob.ar/areas/hacienda/sis_estadistico/banco_datos/banco.php?menu_id=34690.

[10] Hack Electoral, “Elecciones 2011,” HacksHackers.

[11] Cagliani, Martín A. “Las Plazas De Buenos Aires Y Su Historia.” Barriada. Ciudad Autónoma De Buenos Aires, n.d. Web. 25 Mar. 2015.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Turner, Charlotte. “25th May 1810: Evolution of a Revolution.” The Argentina Independent. N.p., 18 May 2007. Web. 25 Mar. 2015.

[14] Argentina.ar. “17 De Octubre. Día De La Lealtad.” Argentina.ar, Argentina En Noticias. Argentina.ar, 17 Oct. 2013. Web. 25 Mar. 2015.

[15] Daniel James, “October 17th and 18th, 1945: Mass Protest, Peronism, and the Argentine Working Class,” Journal of Social History 21, no. 3 (1998): 457.

[16] Promeet, Dutta, Maren Goldberg, and Michael Ray. “Peronist | Argentine History.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, 23 Apr. 2008. Web. 25 Mar. 2015.

[17] Catoggio, Maria Soledad. “The Last Military Dictatorship in Argentina (1976-1983): The Mechanism of State Terrorism.” Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence. N.p., 5 July 2010. Web. 25 Mar. 2015. ISSN 1961-9898

[18] Ibid.

[19] “Speaking Truth to Power Madres of the Plaza De Mayo.” Womeninworldhistory.com. Women in World History Curriculum, n.d. Web. 25 Mar. 2015.

[20] Fraser, H. M. ““Los Desaparecidos”: The Madres of the Plaza de Mayo and the Reframing of the Victims.” Canadian Woman Studies 27, no. 1 (Winter2009 2008): 36-39. Humanities Source, EBSCOhost (accessed May 19, 2015).

[21] Bondrea, Emilia, and Maria Duda. 2014. “Event and the Public Space; The Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, The [article].” Journal Of Research In Gender Studies no. 1: 423. HeinOnline, EBSCOhost (accessed May 19, 2015).

[22] Kurtz, Lester. “The Mothers of the Disappeared: Challenging the Junta in Argentina (1977-1983).” Nonviolent-conflict.org. International Center on Nonviolent Conflict, June 2010. Web. 25 Mar. 2015.

[23] Fraser, H. M. ““Los Desaparecidos”: The Madres of the Plaza de Mayo and the Reframing of the Victims.” Canadian Woman Studies 27, no. 1 (Winter2009 2008): 36-39. Humanities Source, EBSCOhost (accessed May 19, 2015).

[24] For example, during the 1978 World Cup that Argentina hosted many international news teams covered the marches of the Madres.

[25] Relatives of Missing Latins Press Drive for Accounting; 30,000 Reported Missing. David Vidal, The New York, 5 January 1979.

[26] http://www.nonviolent-conflict.org/images/stories/pdfs/kurtz_argentina.pdf

[27]http://www.desaparecidos.org/nuncamas/web/english/library/nevagain/nevagain_001.htm

[28] Davies, Wyre. “Argentina Prepares for Nisman March.” BBC News. BBC, n.d. Web. 18 Feb. 2015.

[29] Wyre Davies, “Argentina Nisman Death: Hundreds of Thousands Rally,” BBC, February 19 2015.

[30] Julian Kreimer, “Marta Minujin,” Art in America2011.

[31] Mujeres En Lucha. “¿Quienes Son Las Rojas?” Web log post. Http://mujeres-enlucha.blogspot.com.ar. N.p., 1 Mar. 2013. Web. 25 Mar. 2015. <http://mujeres-enlucha.blogspot.com.ar/2013/03/quienes-son-las-rojas.html>.

[32] Gentile, Emmanuel. “La Justicia Absolvió a Un Policía De La Bonaerense Que Violó a Su Hijastra Desde Los 11 Años.” Infobae. N.p., 15 Nov. 2014. Web. 25 Mar. 2015.

SoHo Footnotes

[1] Peretz Square, New York City Department of Parks Recreation. (please clean up this reference)

[2] “Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation.” GVSHP | Home. N.p., 13 Oct. 2006.

[3] Homberger, Eric. New York City: A Cultural History. Northampton, MA: Interlink Pub. Group, 2008. Print (page numbers?)

[4] SoHo NYC. “SoHo NYC – History.” SoHo NYC. SoHONYC.org, n.d. Web. 19 Mar. 2015.

[5] Buntin, John. “Gentrification Is a Myth.” Slate. Slate, n.d. Web. 20 Mar. 2015.

[6] From “Median Housing Income” graph provided by NYC Election Atlas (http://www.nycelectionatlas.com/)

[7] Greenwich Village Society for Historical Preservation. “Village History.”GVSHP. GVSHP, 13 Oct. 2006. Web. 20 Mar. 2015

[8] “Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation.” GVSHP | Home. N.p., 13 Oct. 2006.

[9] The History Of The Bowery/Houston Street Graffiti Mural Wall In NYC – Aiko.” Complex. N.p., n.d. Web.

[10] “The History Of The Bowery/Houston Street Graffiti Mural Wall In NYC – Aiko.” Complex. N.p., n.d. Web.

[11] 4. Petty, Felix. ” how Gentrification Is Destroying the Cities We Live in | Read | I-D.” ID RSS. Vice, n.d. Web.