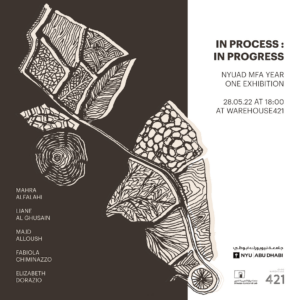

This semester I had a wonderful opportunity to support branding for NYUAD’s MFA in Arts and Media program. Although, in the beginning, I was supposed to help with the marketing and promotion of MFA events and activities, over time my function changed and I suddenly found myself responsible for preparing promotional materials for the upcoming exhibition at Warehouse421. The exhibition is to celebrate the first year of work of the inaugural NYUAD MFA cohort.

Ideation

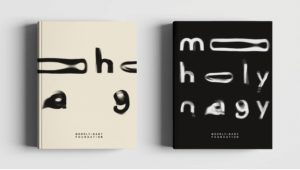

While I was excited to do something big and prepare a visual identity for the exhibition, I felt a bit unprepared. It was only after some time that I realized that posters serve are the main identifier of exhibitions and thus entail a similar function to logos. With the knowledge of branding and logotypes I have acquired over the last semester, I felt a bit more confident.

I must admit it was quite challenging to come up with an identifier that would combine all the works of the MFA artists in an interesting way. Unfortunately, unlike many art exhibitions, I couldn’t simply use the artist’s most popular work as the main design. There are five students at the MFA, each working in a very characteristic style in a unique medium – from video, to sound, painting, pyrography, textile, print, and soft sculpture. Artists’ works examine the instability of the physical world, such as space, country, gender, and the body. Unfortunately, that’s quite a broad range of topics. Moreover, one could argue that the exhibition itself has no universal theme as it serves more as a collection of artists’ work.

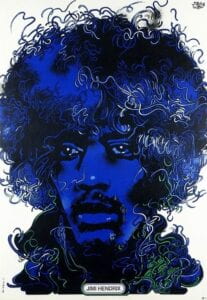

Moodboard. AKA my messy desktop

Brainstorming

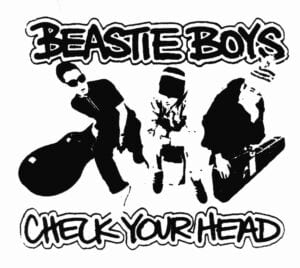

With my team, we came up with a couple of creative avenues I could delve into. The idea of growth truly resonated with us. Moreover, we have found themes related to Botanics quite relevant, as they either permeate the medium artists’ have chosen, such as wood, or the subject of the works. With this in mind, I started to create a mood board and look for inspiration to represent structures, nature, or wood. Bearing in mind the fact that two artists work with fabrics, I also looked into some microscopic photographs of fabrics or cotton.

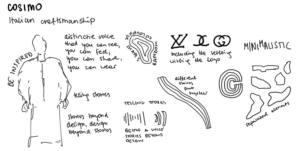

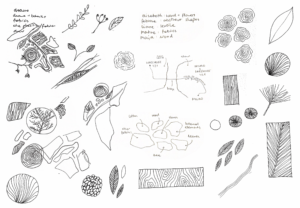

Sketching

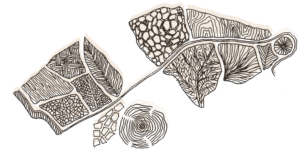

Then I opened my sketchbook and started drawing whatever came to my mind. It really worked like magic. After a while, I settled on the idea of filling some boxes with little drawings relating to the various mediums – botanical elements, wood, fabrics, and cotton.

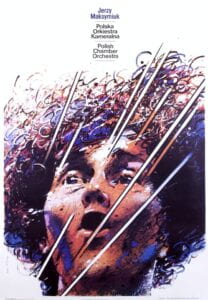

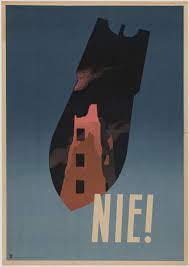

Primary sketches. One can see the “eureka” moment on paper when I draw the path form NYAUD to Warehouse 412

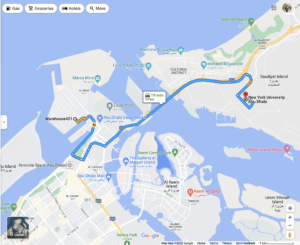

I figured I could arrange these elements in a more systematic order, one that resembles the path from NYUAD to Warehouse421 and contains outlines of Saadiyat and Mina Zayed. This hidden message would allude to the transition of the place of development, New York University Abu Dhabi, to the place of future affiliation, Warehouse 421, the Art Gallery.

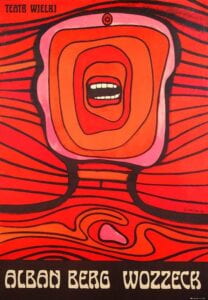

Path from NYUAD to Warehouse421

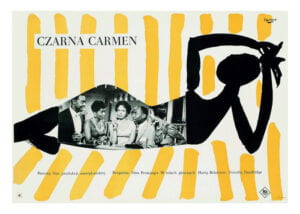

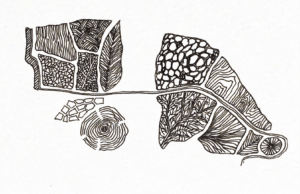

After a bit of sketching I have created a final drawing with black pen on paper.

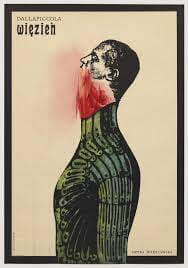

Final drawing

Later on, I scanned the sketch, removed background and played with the shape of it in Photoshop. I have changed the color and added some shadows.

Visual Element for the MFA Year One Exhibition

We have decided to use it as a main identifier for the exhibition, one that will be placed on the cover of the zine and used in external communication.

Revisions

My first proposal for the MFA Exhibition identity involved the choice of blue colour. I liked the contrast it created with beige. In addition to the poster design, I was also asked to prepare the zine, program booklet that will highlight artists, their work, bios and statements. It was only after seeing artists’ work and receiving their portairt photographs, I have decided to change the primary color to brown. Thanks to this change, the booklet looks more cohesive as brown matches the color palate of photographs.