As we have seen over the course of this class, branding is everywhere. Whether we realize it or not we are constantly confronted with brands throughout the duration of our day, from when we wake up to when we fall asleep. For example, now just sitting at my desk, I can easily count 20+ logos in my immediate field of vision. For my last blog post I wanted to focus on something I am passionate about: sports. As soon as I started thinking about this I wasn’t sure how to narrow it down. There is so much branding in sports from jersey deals, team sponsorships, individual sponsorships, etc.

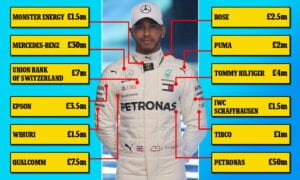

First, there are the obvious partnerships that deal with naming of buildings and logos placed on the front of shirts and the sides of lightning-fast race cars. In Formula 1 we are almost so overwhelmed with branding that you lose the color of the race suit. However, as abundant as these smaller contracts are, the most impressive come from the top teams’ leading sponsors. It is reported that Red Bull pays over $200 million per year for the team to carry the name “Red Bull Racing”. Mercedes is rumored to pay a similar amount for the equivalent naming rights.

These numbers are quite staggering considering that U.S. Bank paid $220 million total for the naming rights of the new U.S. Bank Stadium in Minneapolis, MN (home of the NFL team Minnesota Vikings). Nevertheless, the rationale behind these sponsorships is quite obvious: brand awareness and increasing familiarity.

Building off of this same branding methodology, we see high prices paid for advertising on the front of football team’s kits. For example, in the Premier League Nike has a £900 million deal with Chelsea to provide them with kits for the next 15 years. As far as the sponsorship on the front of the jerseys, telecommunications company Three out of Hong Kong also partnered with Chelsea to feature a 3 on their shirts, tallying a £40 million sticker price. However, as we have seen recently with Chelsea F.C., it can be risky for a brand to attach their name to an athlete or team whose performance and behavior is out of their control. In light of Roman Abramovich’s Russian funding during the war with Ukraine, Three requested Chelsea remove the 3 from their kit and stadium. They did not want to be associated with Abramovich’s ill-behavior.

This is not the only instance of branding mishaps in the sports world, as we have seen with former professional cyclist Lance Armstrong. Armstrong won seven consecutive Tour de France biking races in the early 2000s, all while being a cancer survivor. This launched his brand collaboration with Nike through the Livestrong Foundation. However, when it was finally discovered that he had illegally enhanced his athletic performance through doping, all of his sponsorships were dropped. This is a way for a brand to protect itself from the damaged reputation and image of an athlete. It also highlights the downsides to participating in sponsorships and collaborations in sports and other industries.

Nevertheless, sports still present a big opportunity for companies to grow their brand recognition and emphasize their brand values. Recently, this has become a big topic of discussion particularly in the NCAA. In the new ruling, Name, Image, Likeness (NIL), allows college athletes to monetize their right to publicity. Essentially, in the past they were not allowed to be individually sponsored or having partnerships with brands. This would all be done at a team level, operated by and collected by the universities. However, the recent rule overturn changed this, allowing athletes to begin to build their own brand name and collect signings with companies. An example of this is when Paige Bueckers, a women’s basketball player out of Minnesota, USA, became the first athlete to be sponsored by the popular sports drink company Gatorade. The Wall Street Journal reported that between Gatorade and another sponsorship with StockX, she could make up to $1 million. Why would Gatorade pay her? Publicity. While Gatorade is already a well-established company with a strong logo and product, it lacks the public’s awareness of their brand values. As NIL was a huge discussion in the news, fans of the sports world eagerly awaited big companies to reach out to athletes. When Gatorade announced this, it not only made headlines because of its relevance and timeliness, but because of who they were sponsoring. Paige Bueckers was an extremely popular athlete in her field, but is still a big statement Gatorade made about women’s sports when they chose their first ever college-athlete sponsorship to be with her.

Building on this, we have seen a recent brand collaboration between Olympic gymnast Simone Biles and GAP’s female sportswear brand, Athleta. Biles ended her deal with Nike which had been in place for six years in favor of a new collaboration with Athleta. She did so because she felt she aligned more with the brand values at the womenswear company. Athleta’s slogan “Power to the She” really resonated with Biles as she saw a company built on lifting women and girls up through sport. This proved to be a valuable switch for both Biles and GAP when the gymnast experienced the “twisties” during the Tokyo Summer Olympics. After pulling out of several events mid-competition, Simone Biles said she needed to do so to focus on her mental health. Sticking by her side, Athleta then became associated with mental health, not only an important health condition, but one gaining much attention in recent years. This allows GAP to gain positive publicity surrounding their brand and their values/ethics as a result of their partnership with Biles.

Overall, we see an immense amount of branding in all athletic spaces. While it may be a risk to companies to associate themselves with an identity outside of their control, the benefits are often worth it. I believe that over the coming years we will continue to see sponsorships, especially in the new NCAA space, flourish and grow monetarily exponentially. One example of this is the continual growth of prices to advertise during the NFL Super Bowl, as this year 30-seconds of advertisement space was sold to companies at a whopping $6.5 million to reach its 112.3 million viewers.

https://onestopracing.com/how-much-does-it-cost-to-sponsor-an-f1-team/

https://sportsnaut.com/super-bowl-lvi-commercials-cost-6-5-million-per-ad/

https://www.nfl.com/news/super-bowl-lvi-total-viewing-audience-estimated-at-over-208-million

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/U.S._Bank_Stadium