Entering the last month of this spring semester, I took some time over the Eid break rereading some of the posts made by my peers. Seeing our collective knowledge on wayfinding and design being broadened and applied, one post at a time, further highlights the pervasive nature of design in our daily lives. Blown away by the depth and diversity of the thoughts presented by each post, I wanted to take this time to write about some of the learnings I’ve had from my peers.

Hasin’s writing made me realize how the approach taken in the design process directly affects the quality of work produced. Hasin talks about his creative process that comes from a combination of introspection and giving ideas a physical form, in the form of sketches, scribbles, and lines. These forms might not initially have a clear meaning at the moment of creation but the visualization opens doors to future possibilities for the designer to make sense of their thoughts without relying on memory. This process itself can give rise to new ideas. Seeing the quality of work Hasin produced for his pictogram definitely inspired me to take on a more hands on approach in my next design assignment.

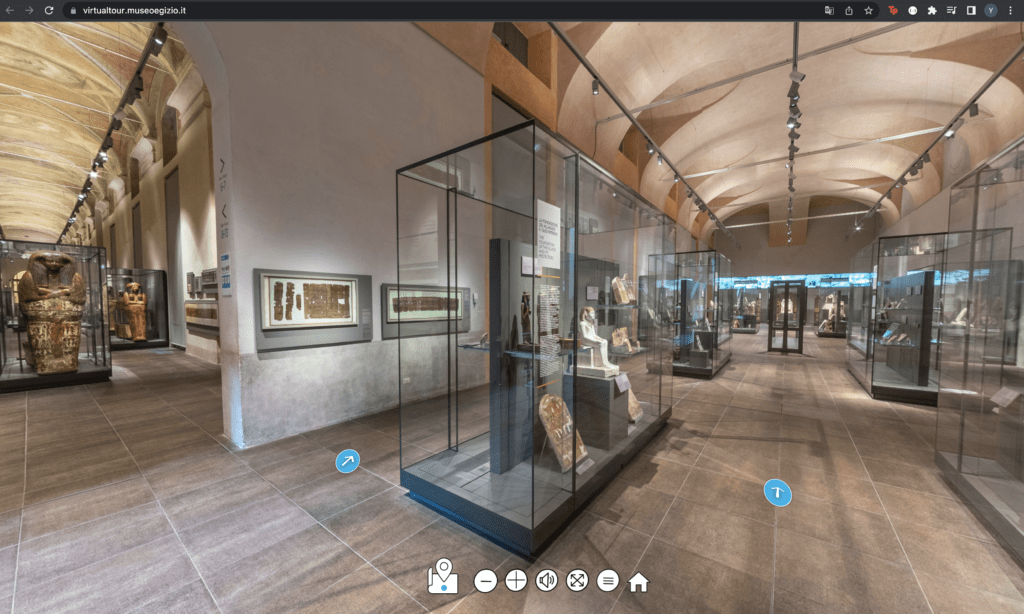

Abdelrahman’s post points out the inability to fully enjoy the convenience and accessibility of artifacts presented by museums, when not given the entire history of how they got there. It is true that artifacts made by humans, whether they are from Egypt, Korea, UAE, etc, tell a story about our collective humanity. But, some artifacts hold more significance to a certain group of people over the other. In most cases, the origin country in which these artifacts were birthed in, used and developed should have ownership over these objects and how their stories are presented to the future generations. If the artifact is displayed elsewhere, an ethical exchange and borrowing of artifacts is crucial to ensure that the origin country does not feel violated and stolen of their precious artifacts. Unfortunately, from history, it is clear that these exchanges did not always occur in ethical ways which provokes a sense of discomfort when encountering artifacts foreign from the location of the museum. It makes us question, “How did it get there?”. Unfortunately, too often, we are not given an honest answer from the beholders. In most cases, the process of how they got there is forgotten and not given enough attention to, perhaps with intention.

I could sense Abdelrahman’s passion for design that stemmed from all the way back in 2013, prior to taking Wayfinding. It was interesting reading how even as a designer who has been active for the past 9 years, one’s idea of what design is and should be is continuously reexamined. The ambiguity of the word “design” provides this flexibility for redefinition based on context. Perhaps the question of what design means and should mean is one that we, as designers, should always ask ourselves and reexamine based on the context in which the design is applied.

Laura’s post further provoked more ethical questions regarding the ownership of artifacts in museums. The line

“But if objects carry these words, these messages, and even lessons about history, adding value to the society of today, one could argue that owning these objects would equal owning history”

made me question, where does the identity of objects lie? Is it simply in the location of residence? The owner? Who owns artifacts?

Considering the change of ownership that occurs throughout history, the narrative containing how artifacts end up on the hands of multiple owners should also be presented and made more transparent by the museum. Presenting the viewers with not only the context of creation and the ways of usage but also how the artifacts have gotten to its current location.

Laura also presents us with the question, “Is history purchasable?”

Let’s say a country managed to purchase an artifact from another country, giving them the right to use and display the artifact freely. Can they truly own this piece of artifact in its entirety? The history stored within the artifact makes it impossible for its previous identity to be fully erased with money as long as we, as viewers, remember it and keep it in our record. Hence, the non-tangible identity and history of the physical artifact seems to retain its value regardless of its physical location as long as the story is remembered and told.

I believe that it is part of the museum’s role to preserve the artifact’s story and history in its entirety, up to the point of how it got to the very museum it is stored in. Laura also points out how “the preservation of history should be the goal regardless of who owns it”. This made me think whether preservation and the act of recording history is always better than having no record? This question becomes even more important for preservation processes that involve stealing and a complete disregard for the ethics of the origin country. Are some artifacts better off not being discovered, protected under the grounds of their origins, until the country is ready to unravel and showcase them at their own pace? Do we always have to adjust to the pace of discovery and preservation of the “faster-developed” countries?

Prior to reading Jennifer’s post, I thought that the usage of analogy, metaphor, and synecdoche was limited to text and speech. Having read her post, I now recognize the power of using them in visual communication to leave a more permanent and striking impact on the viewers. It made me think about how an analogy could be successfully executed in visual form. It seems from the examples presented of the Hiroshima posters, the visual analogy can be supported by text to provide further context of the image. The WWF, on the other hand, provides the context entirely through visuals achieved by including more details onto the abstraction – in this case, adding the individual constituents of the ecosystem, the animals, inside each block of the Jenga to represent the fragility of the ecosystem as a whole. The abstract way of thinking, encouraged by the usage of analogies, metaphors, and synecdoches, in visual form allows room for freedom to be creative in the design process.

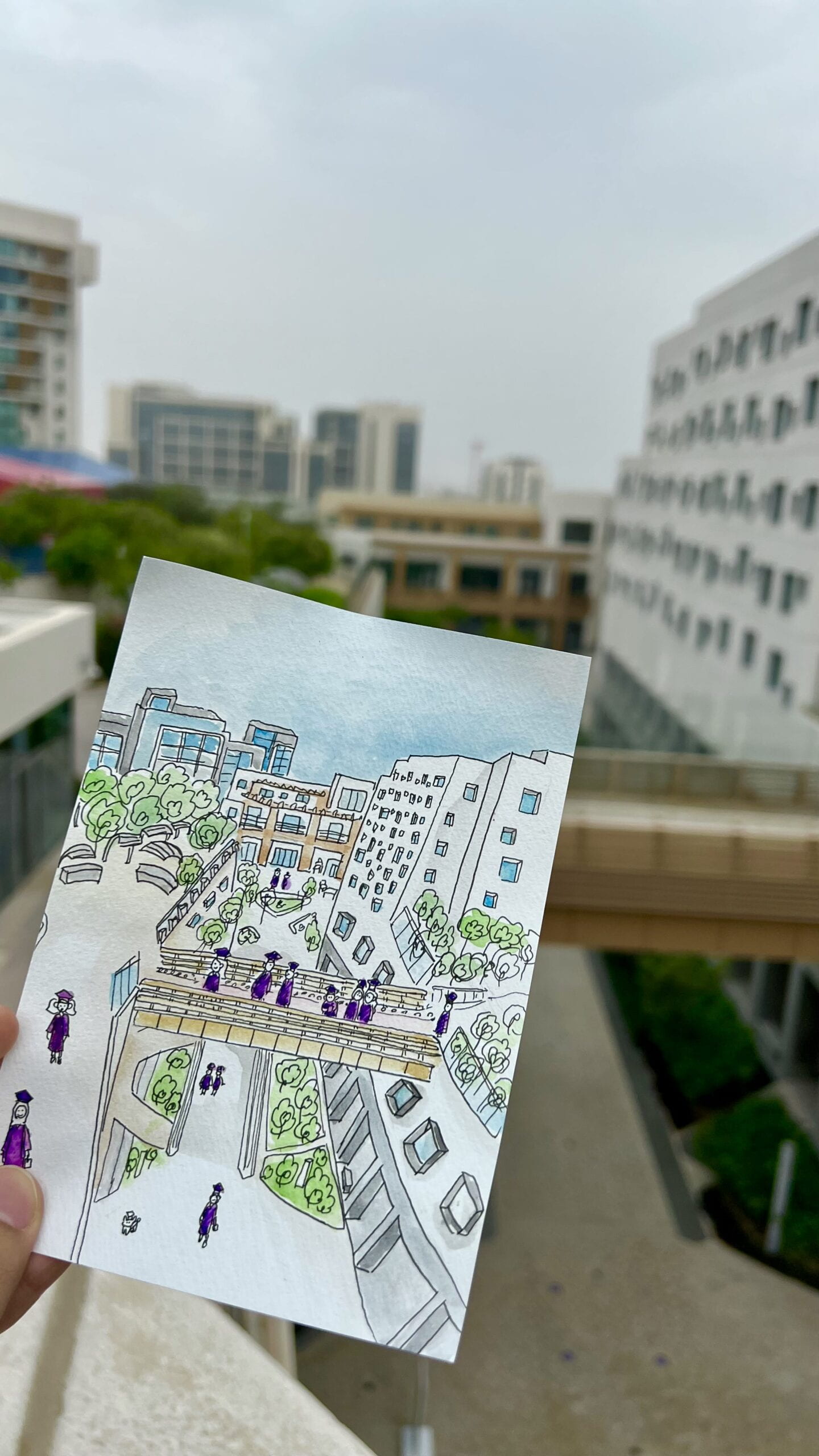

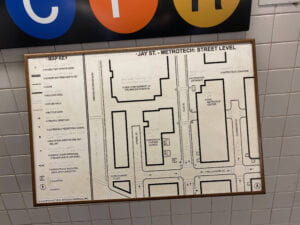

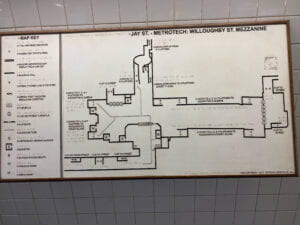

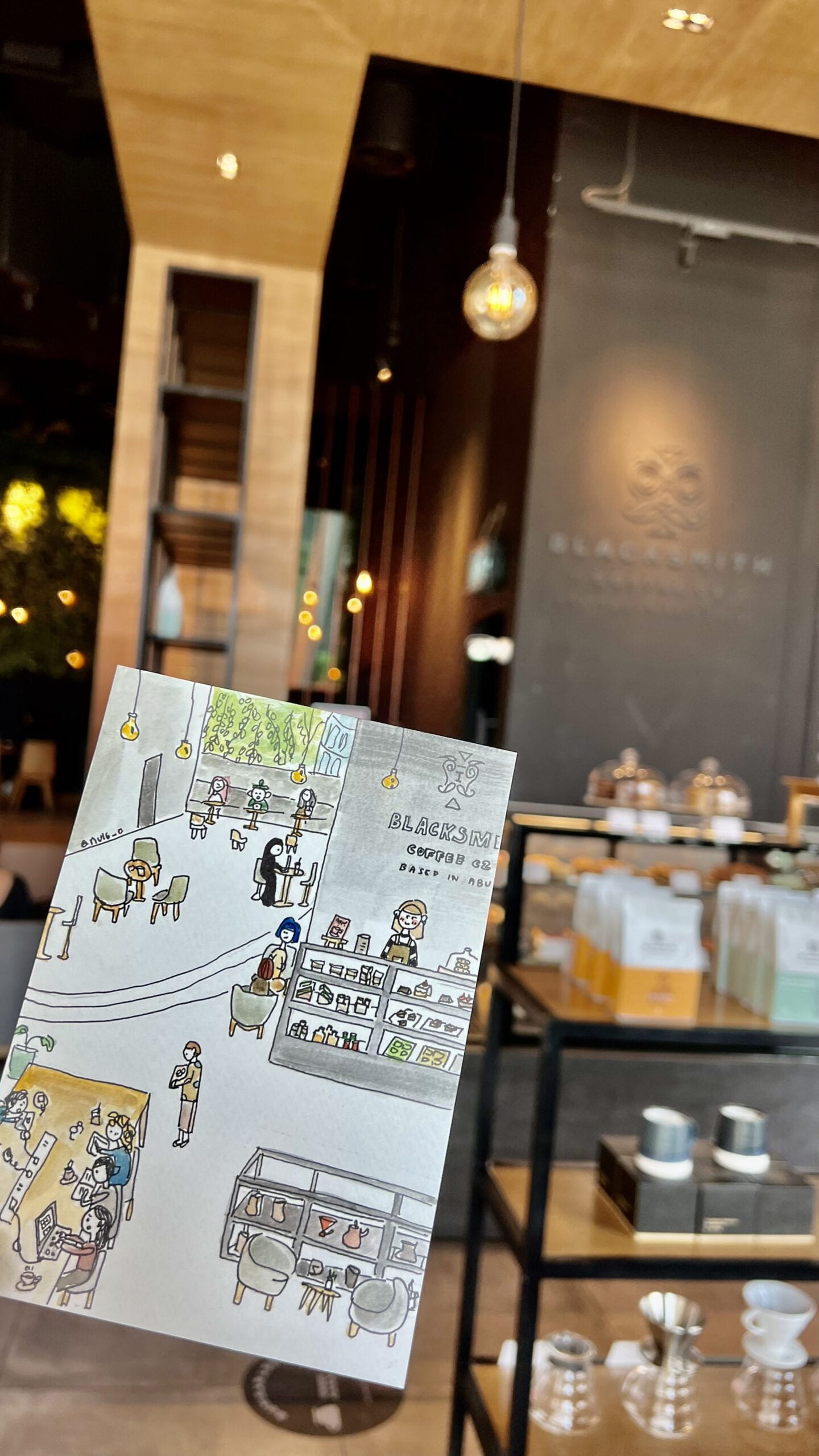

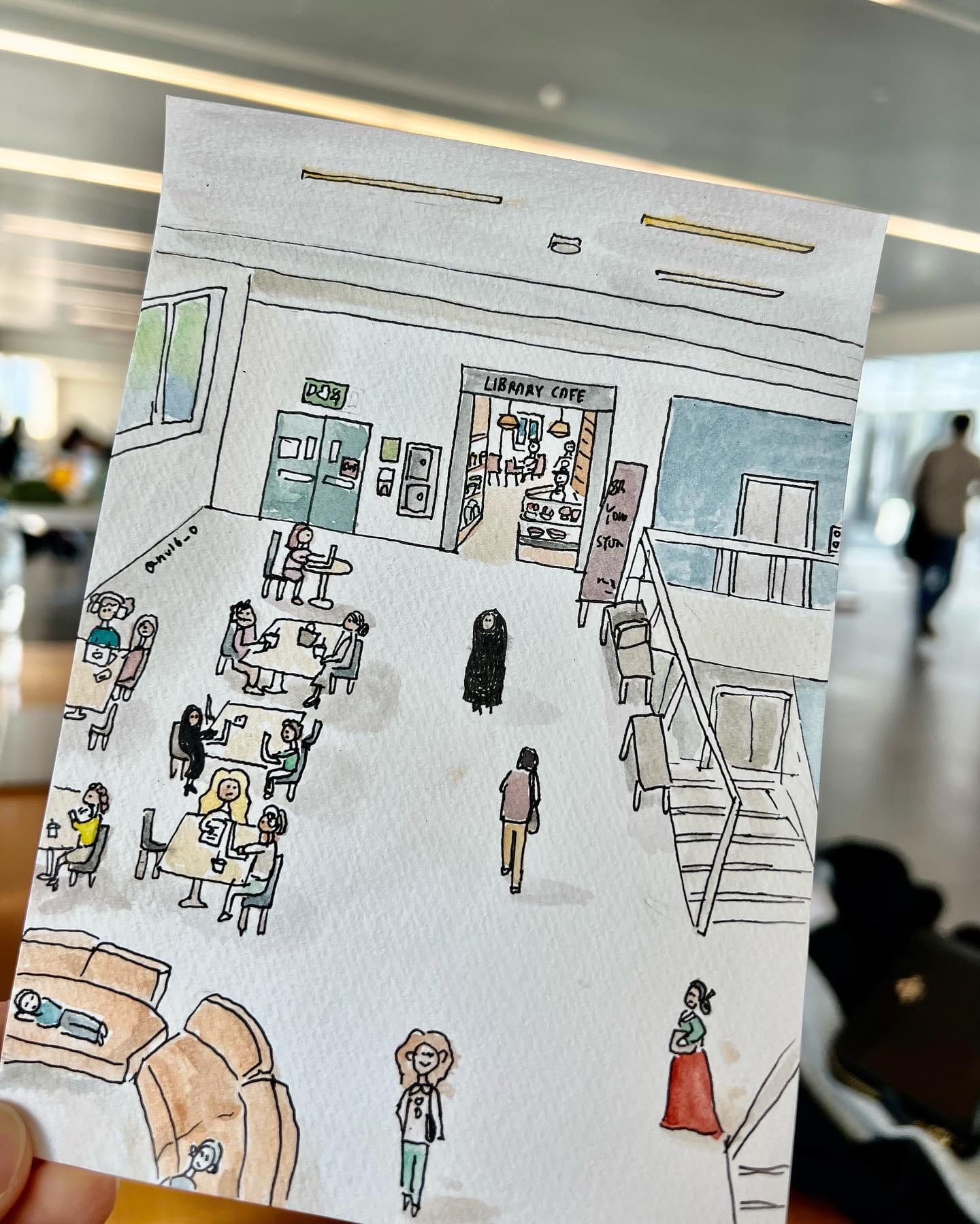

To conclude this blog post, I wanted to share some new additions to my campus illustrations series made throughout this semester, inspired by the conscious decision to be more attentive of the physical systems that surround us on a daily basis.