When I think of the impact Wayfinding has had on my life, I’m grateful (and surprised) that the scope doesn’t just end at “design.” I enrolled in this class, hoping to learn about designing tools, maps, and the definition of “wayfinding,” but I ended up learning more about their importance and how they can be used to achieve personal, economic, and political goals. Given the maximum potential of practicability that I gained from this class, I’d like to dedicate my last blog to the main lessons I got from this course.

“Because maps have so many decisions behind them, they are more than just designs, they are part of our perception of experiences.”

The first one is very unexpected and breaks stereotypes. Before this class, if someone wanted to talk to me about maps, I would have formed the thought “how boring.” But apart from any prejudices I might have had about maps being uninteresting before this class, I think generally speaking maps has never been a topic you see people being particularly passionate about—it has become almost like a niche. However, after our lectures with Giuseppe Attoma and Jug Cerovic, I can never see maps the same way. Firstly because I know that they are not completely accurate (geographically speaking) and second because I know the impact that the latter piece of information has had in using maps to alter politics and influence history (e.g. the map of Berlin). Now, everytime I go out and I use a map, I find myself thinking how much it was altered to look like that, simpler and more practical. I wonder if there is any particular reason for every silhouette or figure or change the person in charge decided to include. In short, maps have become something more familiar to me, and I can appreciate the role of maps better because of these learnings. I know now that because maps have so many decisions behind them, they are more than just designs, they are part of our perception of experiences.

“Because maps have so many decisions behind them, they are more than just designs, they are part of our perception of experiences.”

The second lesson I want to take with me is the link between making good design choices and creating more reliable, strong material and messages. Learning about hidden cues that lead to people’s interactions with objects (nudges) and the purposeful use of typefaces taught me that nothing in design is by chance—it has an intention and a goal for which the design was made for. It is not the same using disruptive and disorganized typefaces than using more delicate and simple typefaces to a formal message. There is a reason why the same texts can have different impacts on people’s perceptions of them by changing the typography. Moreover, the use of the concept of nudges can prevent utter disasters in museums and other important places that hold value to history and society (or even just daily spaces that hold things that are important to us). These concepts are not just practical in design, but are useful in day-to-day tasks and should be concepts available to all.

“Ethics makes good design.”

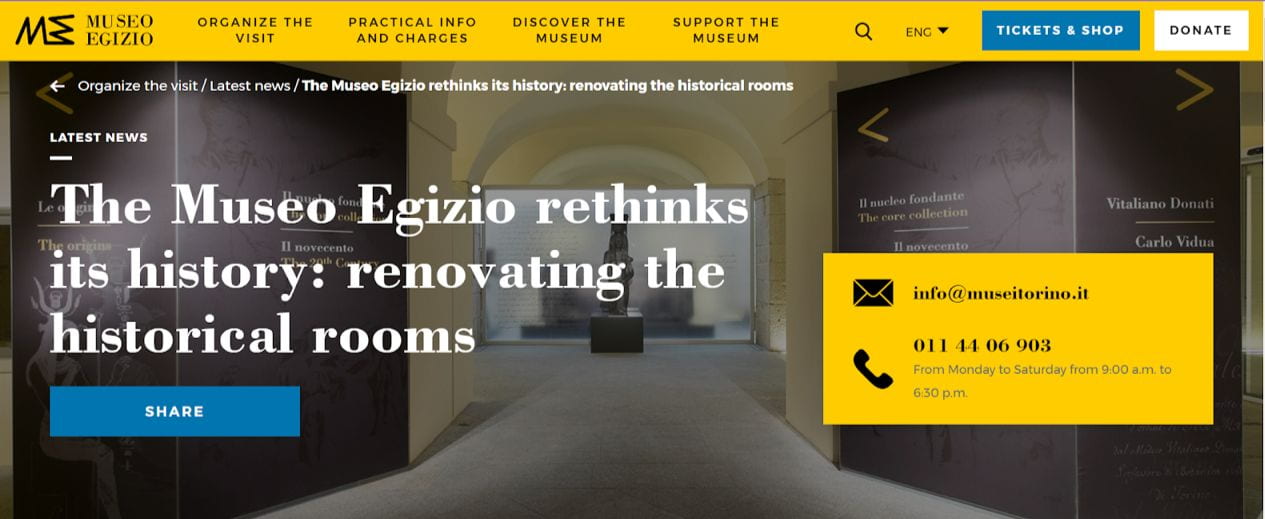

The final lesson, and personally the most interesting, is that ethics makes good design. When working on the presentation about Edward Tufte’s “Visual Explanations,” I remember being particularly excited about his point of the lack of comparison and truthful research being signals for untrustworthy conclusions. In other words, how being ethical was actually beneficial to the researcher, whether or not that could lead to arguments against their work. Moreover, we can see this point in Christian Greco’s work at the Museo Egizio, where his intentions for remodeling the space come from accepting that the objects they possess truly belong to Egypt, not Italy. From these two examples, I’m truly confident that the best designs come from ethical grounds, not only because of the content, but how their content can contribute to society.

After the previous reflections, I can say that visual design is key and necessary in conveying the messages of today, and wayfinding design related knowledge is without a doubt very resourceful to achieve this. I’m hopeful about the way I will apply this knowledge in fighting for inclusion and equality in the future, and peacefully knowing that truth always wins, even in design. To conclude, I just want to highlight how design keeps surprising and offering humanity tools to build the future they want to live in, whether that looks like ethical museums, inclusive signage, or innovative maps.