If truth be told, when I first enrolled in the “Wayfinding: Graphic Design in the Built Environment” course, my only motivation for enrolling was to be done with one of my core requirements. I not only did not have any interest in this topic, I wasn’t even sure what wayfinding actually meant! Though the word itself is pretty self-explanatory, I wondered how is it possible to have a whole course based on simply finding the way?

Only now that I have completed this course, I have not only realized the vastness and significance of this topic, but through Professor Goffredo’s rippling energy throughout the semester, I have actually become passionate about user experience and have acquired a highly observant eye when it comes to wayfinding systems.

While I have already documented my learnings from the topics covered throughout the semester such as principles of affordance and nudges, motivation and convention in pictograms, use of wayfinding strategies, principles of simplicity and redundancy, and more in my previous blogs, I will be highlighting some of the other attributes and experiences that I gained from Wayfinding that I am utterly grateful for.

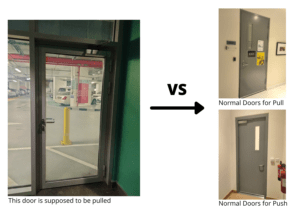

The first time Professor Goffredo showed us a picture of the inaccessible use of stairs on the beach, none of us had any clue what was wrong with the image. Now, whether it be the buttons on the lift not being accessible, or no sound indicating the arrival of the lift, or lack of braille systems, or only the presence of stairs to reach the Torch Club, or the accessible ramps to the underground markets in Tbilisi that I noticed on my Spring break, accessibility or the lack of it, is the first thing that grabs my attention wherever I go! The course has opened my mind and eyes to think from new perspectives and especially realize the privilege that I have if I couldn’t even notice what was so evidently wrong with the picture.

Similarly, despite having lived on the NYUAD campus for the past 3 years, I wondered how I never noticed the inaccuracies and inefficiencies in the wayfinding system on our campus. However, on the first day of in-person class, when my 3 peers and I were assigned the task of finding the flaws in the wayfinding system from B1 to Torch Club, we were able to gather over 30 flaws in the system! This wasn’t because there were so many, but being a part of a group which possessed such diverse experiences and intellectual backgrounds, enabled us to share our individual experiences, get inspired from each other’s ideas and further continuously build upon them.

Similarly through other group exercises when we had to discover an ideal way to cover up Roberto’s piano to protect it during house renovation, we were able to arrive at the perfect solution – covering it with a large wooden triangle. We were only able to do this by continuously building upon each other’s thoughts. Through these group exercises, I learned that no ideas are “stupid”, actually far from them, and therefore became more confident in my ability to express opinions and share ideas in groups. It is also by working with my peers I attained great knowledge from their personal experiences and skills. I learned how to make simple presentations with great design from Yeji, impactful logos from Abdelrahman, maps from Muskaan, as well as gained so many insights into the wayfinding systems back in their hometowns, ranging from airports, streets and even museums!

Moreover, my experience in this class was further enriched through the opportunity to listen and interact with some of the most renowned wayfinding and design experts, such as Guiseppe Attoma and Jug Cerovic. To be able to directly learn from their first-hand, large-scale, impactful, future proof and global experiences, and through their advice and feedback perfect my own designs and channel out my inner creativity during their workshops, was definitely no less than a privilege.

If I had to volunteer to design and implement signages around campus for a Networking Night hosted by the CDC to guide employers from B1 and Welcome Center to Torch Club, I probably would have never and instead would have thought of it as a “boring task which only involves printing and sticking arrows on the wall”. However, only when I actually partook in this activity after being inspired to implement my learnings from my Wayfinding class, did I realize the extensivity and critical thinking required to effectively accomplish it.

What made the task even more challenging was that we had only 5 signboards which needed to cover the entire area from Welcome Centre to Torch Club, as well as, from B1 to Torch Club. As this was a problem that I had already discussed extensively when I was put in a team with Yeji and Muskaan for our first ever group assignment, I was able to immediately able to present a thorough plan for this to the CDC staff, in fact very similar to our presentation in class to our “client”.

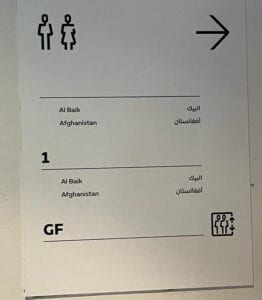

To solve this problem, the CDC initially sent out an email to the employers with a campus map to direct them to enter from the East Parking (so they are closer to the Torch Club with fewer chances of getting lost in the enormous parking lot which barely has any valuable signages). We also highlighted on the map the position of the lift (at the West-most end of B1) so they can take the lift directly to the Torch Club. For greater apprehension of the parking lot, we also put up an overview of the color-coded zones in the parking lot so they could understand their current location in relation to their intended location.

This then allowed us with greater flexibility to utilize most of the sign posts on the way from Welcome center to Torch Club. Out of the 5 we had available, we used an additional one to place right when the employers entered the parking lot to tell them which direction they need to go for the Tawasul Night in case they get confused about East and West wing. The rest of the 4 signages were then placed at every intersection from the Welcome Centre to the Torch Club lift at appropriate distances. In the end, it was very rewarding to know that none of the 30 employers had any difficulty in finding their way to their destination.

So to conclude, whether it be any casual detail mentioned by my peers, or Professor Goffredo’s flat tire game or 1 minute rapid presentations, every small detail and interaction eventually led up to allowing me the courage and potential to take authority and implement such a project to perfection. As Darren Hardy once said,

“It’s not the big things that add up in the end; it’s the hundreds, thousands, or millions of little things that separate the ordinary from the extraordinary.”