Whether it be catching a flight for a Spring Break holiday, heading downtown to the Corniche, or just getting to a class in A6 on time from A2 – we are always navigating through the world in an attempt to get to our desired destination. Sometimes this task is straightforward if routes are easy to navigate. Other times, they may be frustrating and have you going around in circles.

I have always loved traveling and exploring and everything that comes with it: the unknown territory, the finding your way, the uncertainty, and the adventure. With a map in hand and an eye out for signage and directions – I love leading people through new cities, navigating through airports, and the chaos of finding your gate on the other side of the concourse or calling ‘shotgun’ in the car so I can navigate the Google Maps route. There are so many times that I have felt defeated or incompetent when I get lost – or get others lost. It is frustrating when I can not reach where I want to go on time or as easily as I hoped – especially as I pride myself on having a good sense of direction.

Just a couple of weeks into the course, I have begun looking back on such situations with a fresh set of eyes. Perhaps these instances should not have me questioning my sense of direction. Perhaps if there was some sort of signage or some accurate visual representation of the area – if the environment was better conducive – I would not have gotten lost in the first place. Our campus serves as a microcosm for this. There are so many examples of bad wayfinding designs that we have already seen on our very own campus. How can we expect first-years to get to classes on time during the first few weeks of the semester? How can we expect visitors to get to meetings on time? It all goes back to wayfinding and the aspect of user-centered design.

The idea that the “user is always right” is a common mantra in the design world. Good wayfinding design should keep the user and the user experience in mind. This mantra was enforced during our second lesson of the semester through a simple game of Pictionary. In an attempt for the class to remember my name through a simple icon, I decided to draw a smiley face. I chose this because ‘Muskaan’ translates to smile in Hindi and Urdu. However, what I failed to keep in mind was that just because this connection made sense to me, does not mean that it makes sense to everyone – all the users. What if the user interprets the entire emoticon icon rather than just the smile element? Or what if the user does not speak Hindi or Urdu? Does the image make sense then? Again, this served as a microcosm to show that design does not always have the user experience in mind and to be mindful of this when designing. Would it be nice for it to? Yes. Is this reality? Most often not.

To keep the user experience in mind may mean broadening your horizon of what a user is – keeping in mind that you may not be the only user. In the real world, we see this with issues of accessibility, language, typography, brand identity, etc. Are stairs needed, or would a small ramp do the same job – while allowing wheelchair user accessibility? Does this font interfere with comprehension for those with dyslexia? These questions were not obvious to me initially when looking at wayfinding. However, their importance has become highlighted just a couple of weeks into this course.

Such questions should guide designers when designing wayfinding systems. Wayfinding systems, in any form, should guide people and allow for seamless navigation. They should not pose additional problems or confusion in navigation. Perhaps a wayfinding system is most effective when the user is not alerted of its presence. In other words, when the system is integrated seamlessly within the built environment and provides accurate and complete information to a user, the user will have an uninterrupted journey. Perhaps I can assist my argument here with a counterexample.

We do not have to look too far to see bad wayfinding systems. Let’s take a look at our campus. The signage system around campus is full of inconsistent language and ambiguous – or even outright incorrect – directions. This can leave the user confused and disoriented. For instance, we have seen two pillars opposite each other point in two different directions to the same place. Where actually is it? Looking at those signs, I guess we will never know. The current signage system may cause users to take a second, stop, and reevaluate their surroundings to decipher which of these directions are accurate. The signage system should integrate itself into the greater campus system and almost be unnoticeable to a user. It should not force them to stop in their tracks and evaluate the directions themselves. In that case, what would be the point of the wayfinding system anyway?

Examples of Bad Wayfinding signage systems on campus

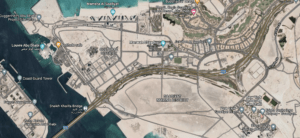

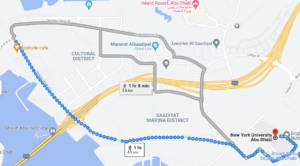

Widening our scope beyond NYUAD, let’s take a look at the greater Saadiyat Island. One of my first weeks on campus last spring, a friend and I went to the Lourve Abu Dhabi. We decided to walk back to campus. Google Maps found us the shortest route – which would take us about an hour. However, when we looked into the satellite view of the path, the path consisted of a nonexistent road supposedly located in the Saadiyat Marina District. If we had not examined the path ourselves, we would have been looking into an area of sand and construction, and perhaps our walk to campus would have turned into a nightmare. Interesting, right? Isn’t it fair to assume that Google Maps is reliable? Apparently not.

Source: Google Maps

Source: Google Maps

Source: Google Maps

All this to say that wayfinding is everywhere. We use it almost every day, and it must be integrated into the built environment in a conducive and efficient manner. A couple of weeks into this course, I realize that perhaps this class may be a blessing and a curse. It has become difficult for my friends to take me anywhere without me commenting on the “bad wayfinding” at least once. I have become more aware of the disruptions that a bad wayfinding system can cause as a user. At the same time, however, being able to notice these disruptions is the first step in being able to fix them. As Professor Goffredo mentioned in class, our position as students at NYUAD is a unique one. We are within a system that is just getting started, which means we also hold the ability to critique, better, and build it.