Design involves creativity; the entire process of building systems based on designs is based on some level of creative process and this process requires thinking. In this blog, I talk about this abstract concept and try to understand what informs our creative thinking process. One way, and a very simple way, might be to ‘just get done with it’ or to Google it though, as made clear from our class interactions, this practice is generally not healthy for creativity and is very frowned upon and rightly so. After all, Google tends to demonstrate that my creativity is the same as millions of other people searching for some idea and as a good designer I should refuse to accept that. Instead, I should meet Google’s suggestions with a rebuttal and instead dig deeper into my own creative horizons. The question is, what does that process look like? And I titled this blog as ‘a guide’ because the way I try to answer these questions form a flow that might help inform the creative thinking process of my fellow designers.

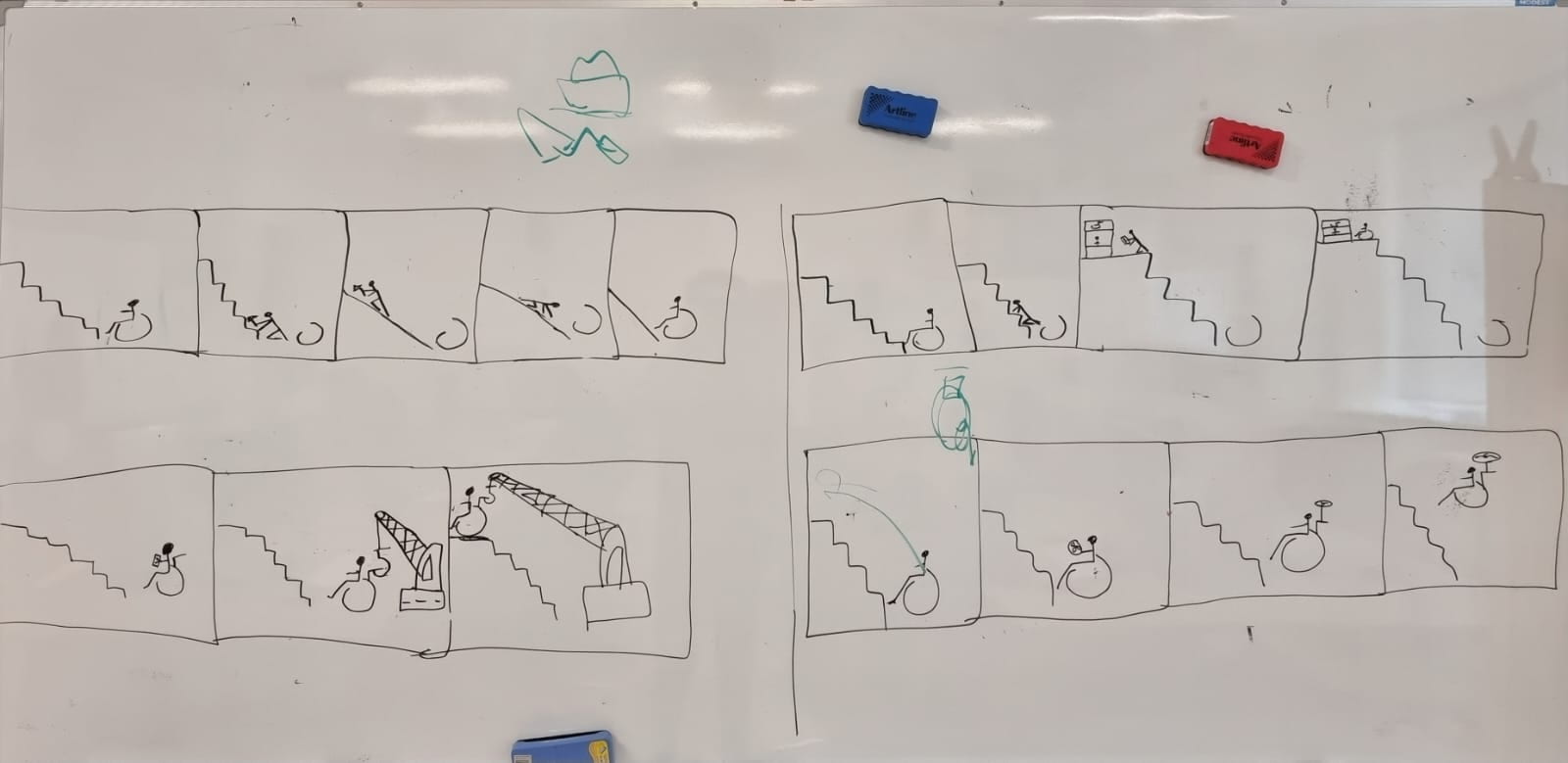

When talking about designing something, the very least that a designer has to do is to come up with ideas. It is these very ideas that will translate into something that gives meaning to a design. For coming up with these ideas, a designer then has to think of different questions and try to find answers to these questions in order to connect the dots and come up with the one (or many) idea(/s) that will work. This seems to be very complicated so let’s pause for a moment. Before I come to what these questions may be, how about the situation when a designer experiences a thinker’s block and cannot even think of anything, let alone come up with ideas? What if you as a designer are just sitting there staring at the screen hoping for an idea to pop up into your mind but to no avail? Here, you might want to take some help from a friend (who some argue could be a designer’s best friend). Here, a designer picks up their pencil and paper – or whatever equivalent there might be – and starts making their brain vomit onto the paper. Scribbling, scratching, drawing lines, iterating, making the paper full of randomness, but at least visualizing the different things (ideas) floating around in your mind. Though this process might look a bit different for some, with scribbling being replaced by note-taking, the purpose of this exercise is to help the designer make sense of whatever is in their brain, connect the dots, understand the task at hand through visualizing their own thoughts, and then develop a frame within which they want to work. Soon, the designer can find themselves moving forwards in the path of creative process, from just staring and thinking to having something to work on.

The next step would be to introspect these ideas and designs. Surely, not everything would really work for a particular purpose (you can’t just draw a circle when the task demands a square unless you redefine what a square is). So the designer now looks at their ideas through the lens of what the eventual goal is and asks questions like “what do I want to achieve with my design/s?”. The idea behind this exercise is to make the ideas aligned with the use. Thus, naturally, this step would require adjustments, alterations, discarding some ideas, and even coming up with some new ones. Only the ideas that are aligned with the use and will fulfill the goal should be worked upon, rest are irrelevant right now.

Talking about aligning with purpose also touches upon the idea of context. Coming up with a good design is not a very simple process and a good designer must first understand these different nuances of the process to achieve a good design. A good design doesn’t just fulfill some purpose, it usually also tells a story. Narration of this story attaches meaning and significance to the design and it becomes essential for the good designer to think about their design within this context. Rewinding to the talk with Cristian Greco, the director of Museo Egizio, would it be sufficient for the museum design to just lay out the acquired artifacts accompanied by textual information? Does that ‘fulfill the purpose’? Not really because that design would just fulfill the purpose of displaying the artifacts without providing much meaning. Instead, the museum chose to display, design, and lay out the artifacts in a manner that narrates the story of the Egyptian culture from the time the artifacts are from. This is a very precise example of providing context to design so that the user of the design can connect to the story that needs to be told in a very subtle way. So the creative thinking process has to be bounded by and informed by the context within which the designer’s creativity is working.

Is that it? We think, we come up with design, we fulfill the purpose and stay within a context and get our job done as designers? Fortunately for some, and unfortunately for others, a good design demands more. Design has the power to create impact, give identities, and shape the experience of the people within the environment the design is placed. Thus, it becomes a need for a good design to be bounded and limited by ethical considerations. By ethical considerations I do not just mean maintaining integrity and honesty by not copying someone else’s work and presenting it as your own in whatever way, though that is also one of the very important aspects of design and also why Google is bad (it can attach your bias to someone else’s work so much that you can end up creating whatever someone has already done). Here, the ethical considerations take a broader approach and integrate the context within them. Is it okay for a museum to place an artifact from one culture within so many artifacts for another? Is it okay for a design to not be very friendly to people with accessibility needs? Is the design even okay within the society or culture it will be placed? What might be okay in one place might be totally unacceptable in another. But would the adjustments demanded by these ethical considerations mean that my design could potentially fail? Is my design problematic for some context and is it conforming to these problematic ideas that have persisted for so long? Should I use the icon of blood in red color to design something or would it be too triggering? How brutal can my design be and still be okay? This, and many more questions depending on the context need to be answered before deciding on what a good design may be. Otherwise, the creative process collapses when it fails to take into account such ethical considerations because it fails to understand the context. Now, it may be that you are asking ‘how many questions is too many questions and when to stop asking these questions?’ That is an exercise I leave for the reader, try it and maybe stop at whenever you think you have tried enough. Through an iterative process involving feedback, a designer gets better at this.

[Source: https://www.reddit.com/r/mildlyinteresting/comments/3y31j4/here_is_what_bathroom_signs_actually_look_like_in/ ]

Design is based on creative thinking and good creative thinking leading up to good designs takes a multifaceted approach that takes the aforementioned aspects into consideration. Of course, there are design practices like making use of nudges, using specific font faces, use of logos and pictograms, etc. However, these relate more to the process of thinking about design itself rather than the process of creative thinking. Furthermore, the creative thinking process is very broad and varied from designer to designer (or person to person), and obviously there is more to it than can ever be discussed in one blog. However, I have tried to target some very common themes that I myself came to understand as a process in the Wayfinding class – through practice and through theory.

One final aspect that I will now address is the conclusion of the creative thinking process. You as a designer have now found yourself in a situation where you have come up with many good designs. How do you now conclude the creative thinking process and settle on one? Well, maybe discard the first one because it might have many personal biases, though this might be counter-intuitive when the first design might be the best one. So, think about the design through the lens of the aspects discussed in this guide and through the aspects of a good design. Then try and answer the question you ask yourself that which one is the best. Maybe it is the one that fits in well into most of the criteria of a good design coming out of a good creative thinking process. Then select that one and hope it works out. Otherwise, you learn and use this lesson to inform your decision, choice, and creative thinking process as a designer the next time you have to make a good design. Eventually, you become a designer whose creative thinking process is such that the designer translates themselves into their design, making it unique to themselves yet equally or even more effective. And most importantly, you can now differentiate yourself from millions of people ‘creatively’ coming up with designs using Google.

What a great post Hasin!